The beginning of fall semester can be a time of adapting to change and new academic and social demands. That can be stressful for students, faculty and staff returning to campus.

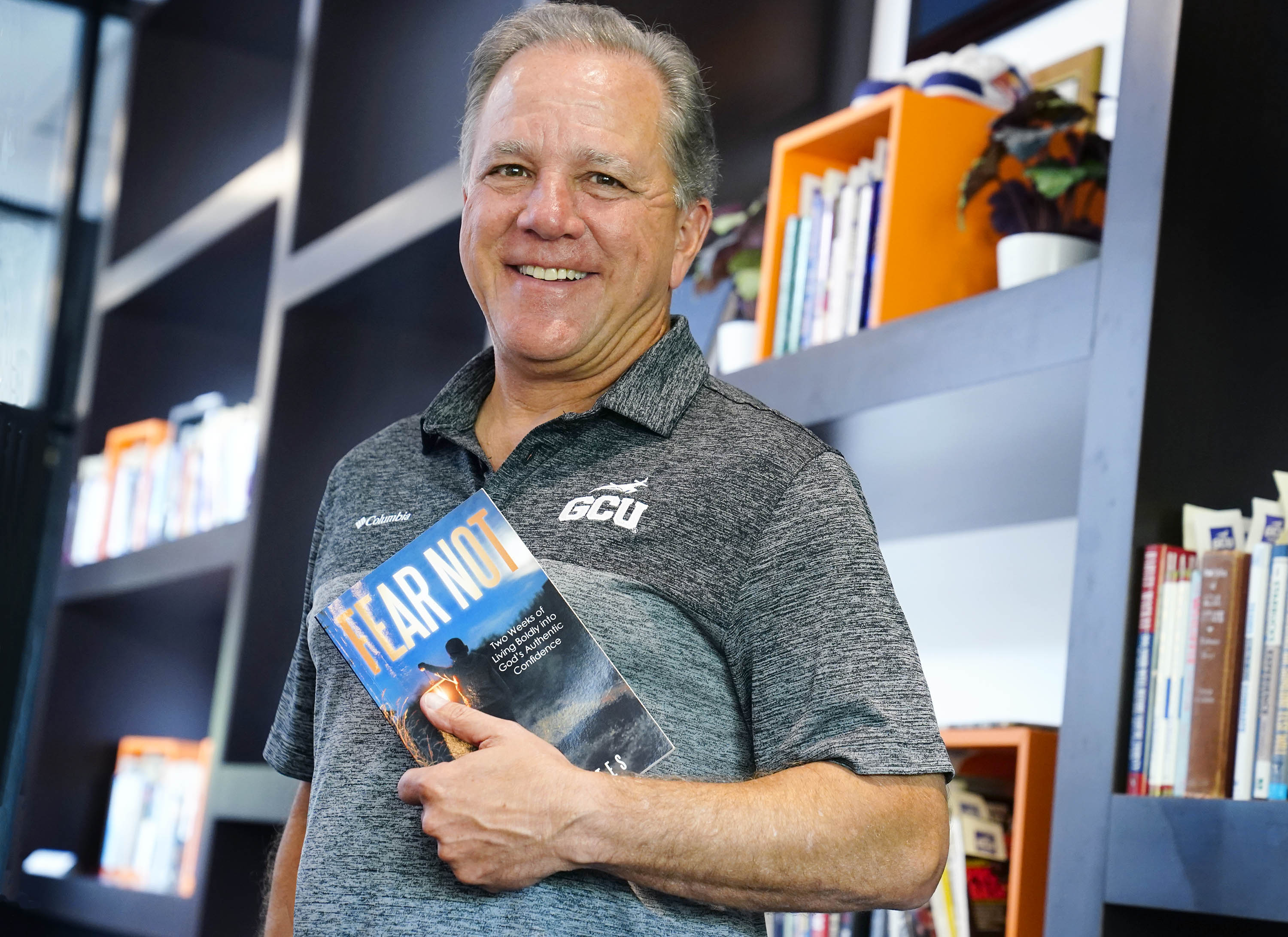

Neil Wattier isn’t going to give you tips to swat the stress away.

Stress isn’t bad, says the Grand Canyon University adjunct professor in psychology, it’s only an interpretation of what we are experiencing.

“Rather than avoiding stress, we must encourage a healthy response to it,” he said. “Tests are not stressful, your interpretation of the event is making you stressed. How you approach any environment is how you experience that environment.

“So what I really try to teach people is treat the experience as neutral. Don’t label it. It is what it is; this is what I am doing. The empowerment comes from what you can do about it.”

Wattier, a 27-year Air Force veteran who trained military personnel in resilience, holds a master’s degree in performance psychology, assisting numerous sports teams in the Valley, and is founder and head coach of Arizona Mental Performance Training.

Anxiety is a mental and physical response to an anticipated future, he said. Create helpful and healthy mental images of future performance, and it can help reduce anxiety.

He offered more ways to be resilient when facing the stressors of a new academic year, some key components of mental skills training.

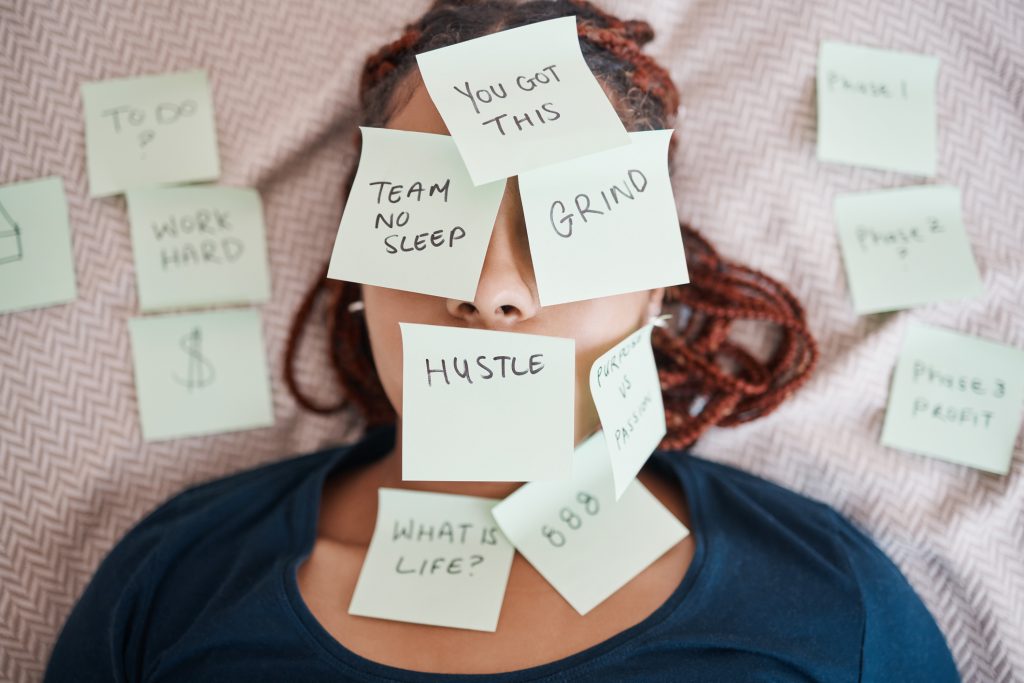

AWARENESS OF SELF-TALK

How do you talk to yourself? You might be coming into the year with a whole bunch of anticipation on how things will go.

“Erase that from your head,” he said. “Just deal with life as it comes, control what you can control.”

Nerves and anxiety can arise from focusing on what you can’t control.

“We have thousands of thoughts every day. The majority of them are intrusive and unhelpful,” Wattier said. “It’s because we are anticipating the future and not focused on right now or the near future.”

It’s not about controlling those thoughts; it’s about regulating them. (“I can control my breathing, but I can’t control my heart rate, I regulate it.”)

Accept the thought, don’t judge it, then let it go and focus on what you can do. It’s a skill you can practice.

Another method is using a performance cue or mantra. For example, Wattier says that when he was working with a placekicker, he developed a performance cue that the kicker said right before he booted the ball: “Relax and just kick.” Or they can be encouraging power statements: “I can do it.”

MINDFULNESS PRACTICE

To some, mindfulness may sound like a word for gurus, but it’s just the nonjudgmental awareness of the present moment. A lot of times we go right to the negative with our thoughts, resulting in increased stress hormones.

For example, as your complaints become more frequent, your neural pathways get more efficient at complaining, he said.

“In order to focus your attention, first recognize where your attention goes,” he said. “Developing your internal awareness is the first step to regulating the dimmer switch, reducing anxiety, regulating emotions and focusing your attention and intensity.”

MANAGE YOUR TIME

Align behaviors with your goals and principles and it can minimize stress by leading to consistency and purpose-driven action, he said. Define your goals and what behaviors get you there. Then create time blocks in a structured calendar for each area of your life – academics, self-care, study, personal growth, etc.

GRATITUDE A GOOD START

A first step that Wattier always recommends is a gratitude journal. Find three things you are grateful about in the last 24 hours and write about it.

What you focus on grows. Ruminate on bad things, bad things grow. Ruminate on good things, good things grow.

“You can’t ignore bad things, you just don’t let them control you. You start to build optimism and positivity. A lot of research is coming out from functional MRIs (magnetic resonance imaging) that show you can reprogram the neurological pathways, but it takes eight weeks.

“Little things done consistently over a long period of time have the greatest impact.”

These “little things” can lead to mental fitness.

It's deliberate training for mental skills, which is just as important as your physical health. That's why I like the term mental fitness.

Neil Wattier

Wattier is careful to distinguish his work in performance psychology from clinical mental health professionals. There are clinical issues that people face that are best helped by them.

But mental training works for many people — if you work at it.

If you go to the gym a couple times a week you might have decent physical health, but if you want to be physically fit, you go a lot more often.

“If you are not doing the mental work you are not getting the mental benefit,” he said.

Wattier helped students create a Sport & Performance Psychology Club last spring and hopes to help create a resilience program similar to one he helped lead in the military.

“We can’t just tell people to be more mentally tough. We can take those skills that have been researched and teach them a skill-based program,” he said. “It’s deliberate training for mental skills, which is just as important as your physical health. That’s why I like the term mental fitness.”

Grand Canyon University senior writer Mike Kilen can be reached at [email protected]

***

Related content:

GCU News: CHSS showcase is a scholarly, deeply personal experience