By Lana Sweeten-Shults

GCU News Bureau

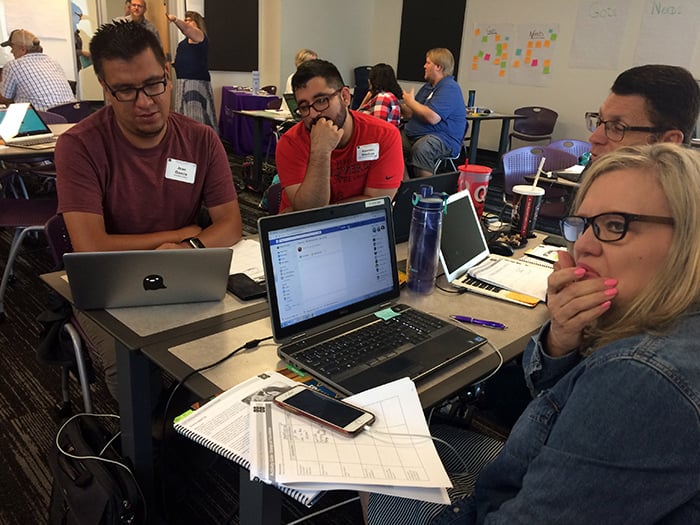

Teachers in groups of three were tasked with finding out as much as they could, in six minutes, about a whole different kind of group of three: the star-nosed mole, Pacific Northwest tree octopus and the blobfish.

Some of the questions about these “strange-but-true animals:” “What does it look like?” “Where does it live?” “What does it eat?”

Some of the answers:

- The blobfish? It was voted No. 1 on Animal Planet’s countdown of ugliest animals because, well, it looks like a gelatinous blob. Poor ol’ blobfish.

- The star-nosed mole scoots its weird-looking tentacled nose against the soil so it can “feel” its way around, since it lives in the dark underground. It also can smell underwater and is the world’s fastest eater.

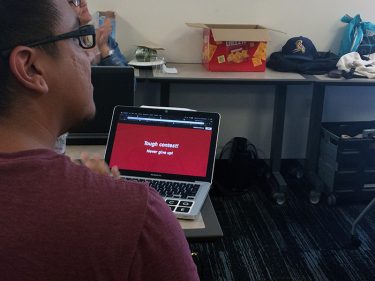

- And the tree octopus – "Of course, that’s a hoax,” piped in one educator with an “aww” of disappointment resounding from his fellow teachers.

He was just one of about 90 Arizona educators recently attending free weeklong Code.org computer science education courses at Grand Canyon University. GCU partners with Code.org and Science Foundation Arizona to boost teachers’ computer science skills and help them teach those skills to their students.

Of course, the lesson wasn’t really to find out more about the star-nosed mole, Pacific Northwest tree octopus or the blobfish. It was to get the teachers to research a topic, then question the information they gathered.

“How do you know the information is correct? What makes the website you used trustworthy?” asked the facilitator of the middle-school level Computer Science Discoveries course, one of the two professional development programs offered by Code.org on the GCU campus (the other is Computer Science Principles, the course educators will use to teach high school-age Advanced Placement students).

The lesson on trustworthy and reliable websites is something the CS Discoveries teachers will bring back to their computer science classrooms in the fall, when they teach the introductory computer science course to their middle school students.

Teaching the teacher

Educators sharpened their skills on website building using the HTML and CSS computer languages, built interactive games in JavaScript using Game Lab, prototyped an app and, of course, answered questions about what makes a reliable and trustworthy website. Those were just a few of the lessons they learned.

“We’re training them to be better computer science teachers,” said Dina Lundblom, a coordinator for GCU’s Strategic Educational Alliances, which supports kindergarten through 12th-grade students and educators and fosters a college-ready culture.

The five-day summertime training, Lundblom said, is the launching pad for a yearlong program. Throughout the year, the teachers will return to GCU for quarterly workshops and also will get online and forum support.

Jasmine Goldstein, a teacher at La Cima Middle School in Tucson, spent some of her time in CS Discoveries problem solving a coding issue.

A line of coding on her screen turned pink, so she knew something wasn’t quite right, though she couldn’t figure it out. That’s when she turned to her “elbow partner” beside her for some troubleshooting help. He noticed that a backslash wasn’t in the right place.

She said she loves how so much goes into computer science: “There’s critical thinking, problem solving.”

Debbie Spear, one of the Code.org facilitators, agreed that critical thinking is so important when it comes to education, and not just computer science education.

“It’s so much more than just learning to program or debug,” Spear said. “We want our kids to experience problem solving, and that has been missed a lot by counselors and administrators. When they look at another elective for the kids to take, they see it as keyboarding, which it is not.”

Goldstein said, “We just had a lesson on strategies to use in debugging when we are writing code. … It could be as simple as the backslash is missing. But those are the things our students are going to come across in the classroom, so we’re kind of learning Code.org strategies, learning-from-other-teacher strategies and learning how to teach out of our classroom.”

A lack of skilled teachers

Goldstein is in her second year of helming computer science courses. She earned a degree in teaching, though she does not have a formal degree in computer science – the case with many of her fellow teachers in the Code.org Discoveries program.

They come from “all different backgrounds,” Goldstein said, with varied experience levels.

Spear said most teachers in the recent CS Discoveries course have taught computer science for one to three years. Only one has taught computer science for four to six years. Many have never taught computer science before.

“There’s no requirements right now for a computer science credential,” Spear said of teachers. “I’m from the state of California, so in the state of California, if you have a math credential, you can teach computer science.”

The lack of skilled teachers in the field – a field that continues to enjoy phenomenal growth -- is just one reflection of the computer science education landscape across the country and how the Code.org training is trying to change that outlook.

Linda Coyle, Director of Education for Science Foundation Arizona, said the first year these teacher-enrichment courses were offered, 10 teachers took the course. Of those 10, seven ended up leaving education to take jobs in the computer science industry, where the salary is much higher. It’s just one example of how difficult it is to compete when it comes to finding and keeping good computer science teachers.

Corinne Araza, SEA's Director of STEM Outreach and Program Development at GCU, said, "It's so hard to find computer science teachers, and so we do need to depend on teachers who are interested in IT and computer science."

Computer science marginalized

According to Code.org, computer science drives innovation throughout the U.S. economy, and the average salary for computing jobs is nearly double the state’s average salary of $46,290. Yet computer science remains marginalized throughout kindergarten through 12th-grade education. Organization statistics reveal that 13 states have adopted a policy to give all high school students access to computer science courses, and, of those, only five give all kindergarten through 12th-grade students access.

Those statistics also reveal how U.S. schools are behind in keeping up with the demand for jobs in the field. In Arizona, while computer standards are still being created for K-12, high schools are not required to offer computer science, even though, according to Code.org, more than 10,450 computing jobs are open in the state. That’s 3.3 times the state's average demand rate. Furthermore, nearly half of Arizona’s schools lack computer science education. Only 16 percent offered AP Computer Science in 2016-17, and only 738 students took the AP Computer Science test in 2017-18.

“But they’re working on it,” Spear said of improving the computer science education landscape. “They’ve got the standards together and the framework and they’re working on it to try to make it so that it’ll be mandatory for all students. But each state is going to have to take this on themselves.”

Code.org wants access to computer science to be expanded in schools. That means training more computer science teachers and developing professional learning programs such as CS Discoveries and CS Principles. The nonprofit also wants to increase participation by women and underrepresented minorities.

According to Code.org, “Our vision is that every student in every school has the opportunity to learn computer science, just like biology, chemistry or algebra.”

Building community

“We work a lot on building community and figuring out who the stakeholders are and who can help to bring computer science to all of our kids -- not just the ones at a handful of special schools,” Spear said.

GCU, whose first computer science graduates walked across the stage in April, sees itself as integral to building that community. The University has partnered with Science Foundation Arizona, College Board and Code.org for three years in an effort to increase teacher knowledge in computer science, SEA Executive Director Carol Lippert said.

Coyle added how industry also has played a big part in these teacher enrichment courses. Schools often cannot afford to send teachers to a professional development program like the one offered at GCU, so several corporate entities have supplied grant money to cover the cost.

With these CS Discoveries and CS Principles learning programs, Spear said, it’s not just about giving students access to computer science in schools so the workforce can meet the demand for the burgeoning jobs in the field.

It’s also about supporting teachers.

The number of educators giving up a week of their summer to learn strategies to teach computer science has gone from 10 that first year to about 90 this year – a 900 percent increase in participation in just three years. And the teachers who attended did so on their own time, which shows how committed they are to preparing their students for the future.

“When you go to faculty meetings, how many teachers know computer science that you can talk about – what you’re passionate about? So here’s their opportunity," Spear said.

“We need that support.”

You can reach GCU senior writer Lana Sweeten-Shults at [email protected] or at 602-639-7901.

Related content:

KTAR: "Arizona teachers trained to integrate computer science in their classrooms"

GCU Today: "GCU is paving the pathway to computer science"

GCU Today: "Students test their gray matter at summer institute"

GCU Today: "DNA gets A-OK from GCU STEM campers"

GCU Today: "Will Cyber Warfare Range have impact? Bank on it"