P18

December 2013

S

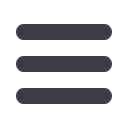

ydney Poolheco

and

Prudence Tsosie

grew up a decade and 200 miles apart in

or near Indian Country, nurtured by large

communities that valued education.

Each took a different path to Grand Canyon

University, which has a Native American student

population of nearly 750 on campus and online.

Both found encouragement, guidance and

friendship in their new homes.

Poolheco, an 18-year-old Hopi from Winslow, Ariz.,

visited GCU during high school. “I grew up being

told I was going to college whether I liked it or not,”

said the freshman pharmacy major. “When I got on

campus, students just came up to say hi, and I felt

like I could fit in here.”

She had traveled to the East Coast on middle-school

trips, so homesickness wasn’t expected. Two weeks

into the semester, however, she felt overwhelmed

and tired, and she went home to see her mother,

Stephanie Poolheco

,

two brothers and other

relatives. It was the right medicine.

Poolheco, who lives on campus and has grown close

to her three roommates, knows that

Kim Judy

,

a

GCU tribal liaison, “has open arms if I need to talk.”

Poolheco meets periodically with Hopi officials

wanting to ensure her well-being, as the tribe

funds part of her education.

“They want Native American kids to go to college

and succeed, to become known as doctors

and lawyers in the world, and to know they can

become anything they want,” she said.

Tsosie, an education major, studies online and

lives in Phoenix with her two children and their

father,

Spencer Dan

. She grew up in Shiprock,

N.M., on the Navajo Nation, and her father,

Larry

, was a school principal. Education was the

family’s priority.

Armed with an associate’s degree from Diné

College, Tsosie, 32, moved to Phoenix in 2005,

planning to attend Arizona State University.

“Coming from reservation land with three stores

and nothing else to the city was a huge transition

for me. I didn’t know how to get on the bus, I

didn’t know the major cross streets. Everything

was so cluttered.”

She put her education on hold and found a job,

working her way up at a local carpet-cleaning

company from receptionist to office manager.

In 2010, she noticed a GCU billboard near

the freeway.

“Something told me later on that this was going to be

in my future,” she said.

That future was 2011.

“When I started out years ago, I didn’t have a

purpose,” said Tsosie, who will graduate next

October. “I have that now, and I like what GCU says:

‘We are going to be here for you from the start to

the finish.’”

Poolheco and Tsosie are inspired by family members

who, in contrasting ways, have spurred them to

succeed. Poolheco is her family’s intermediary with

doctors for an elderly, diabetic aunt. She wants to be

that for her family and tribe, possibly from Flagstaff.

Tsosie wants to return to Shiprock to teach.

“I don’t see a lot of Natives becoming teachers,”

Tsosie said, “and many teachers back home are

older and retiring. And I want my daughter to know

her relatives.”

There’s another reason. In June, Tsosie’s nephew,

DamianYas Chee

, was struck and killed by a motorist

on a highway in northeastern Arizona. At 9, the boy

already knew he wanted to be a school principal.

“I am motivated to do well and finish for him,”

she said.

■

WITHOUT RESERVATION

Hopi, Navajo students are

inspired by others to succeed

– by Janie Magruder

Sydney Poolheco (left) and Prudence Tsosie see the value of having

a college education in their Native cultures. Photo by Darryl Webb