P16

December 2013

University’s ties to school

extend way back

W

hen

Dr. JimRice

was a freshman at Alhambra

High School in 1963, the student body was

mostly white, the teachers – even the one who

taught Spanish – were white, and people moved

into this primarily single-family neighborhood in

Phoenix and stayed.

“Doctors, lawyers, teachers and builders were

born here,” Rice said. “It was the place to be. You

went to Alhambra with the same people you went

to grade school with. Then you grew up and

stayed in the community.”

Five decades later, most everything has changed at

and around Alhambra.

Surrounded by blocks of apartment complexes

that house refugees from Asia and Africa,

Alhambra has 100 refugee students, the largest

population among schools in the Phoenix Union

High School District. New students arrive on

a regular basis, lacking identification cards,

birthdates, English and skills, said Principal

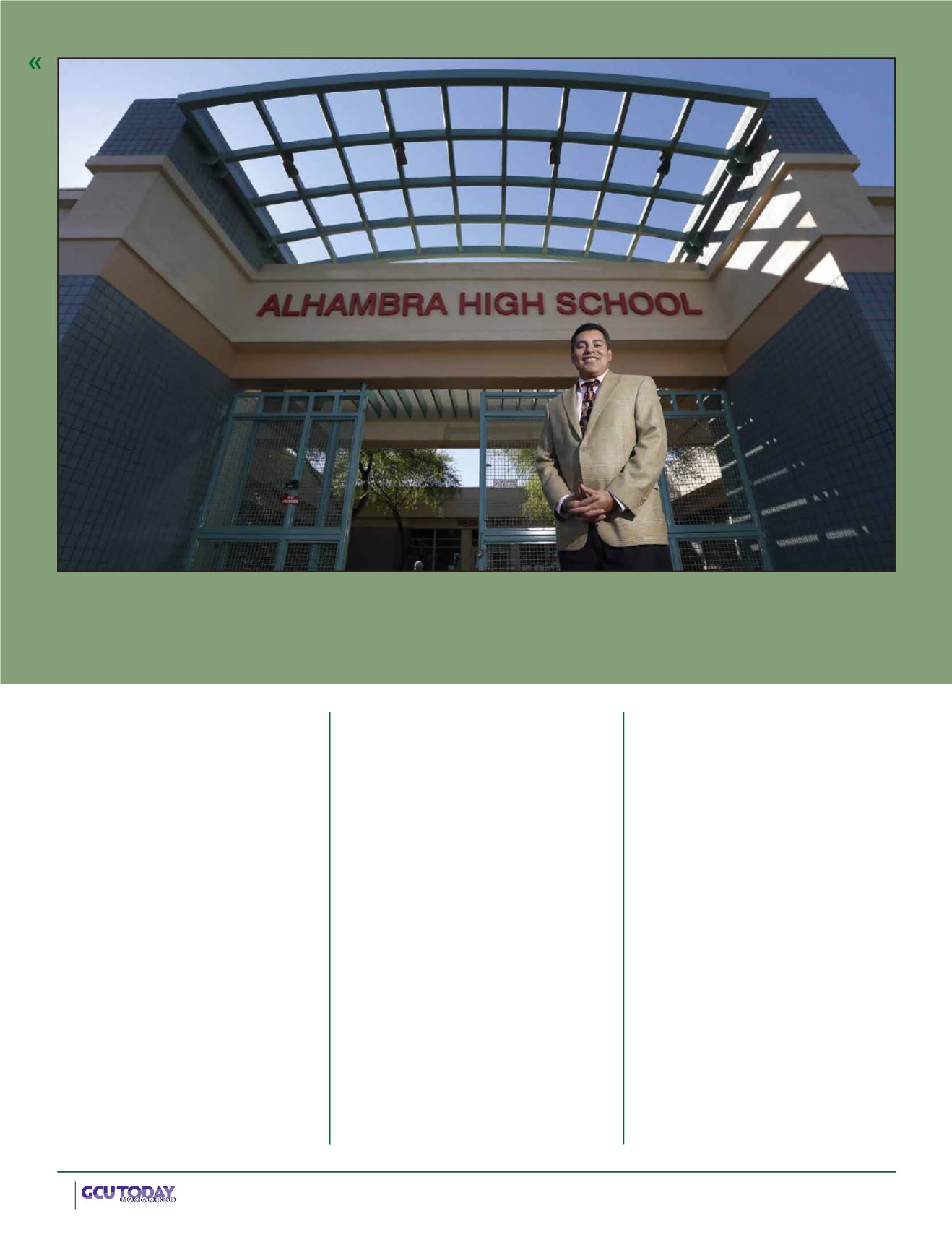

Claudio Coria

. Family stability is a problem, and

students often leave school without warning.

Ten percent of Alhambra’s students are learning

English for the first time. Half of all students come

from homes in which the primary language is

Spanish, but three dozen other languages, from

Arabic and Burmese to Swahili and Vietnamese, are

spoken in the school’s aging hallways.

Alhambra’s demographics are an opportunity and

a challenge, said Rice, a Grand Canyon University

alumnus and a former superintendent in the

Alhambra Elementary School District.

“The greatest change we have made in our

community is we have been introduced to

other cultures from around the world,” he

said. “Multiculturalism is good for a school,

good for the faculty and its students. Our

students don’t see color. ‘Guess who’s coming

to dinner’ is long gone.”

But what many Alhambra students lack is

proficiency in English, reading and writing – making

math, science, social studies and other subjects

arduous, too. That impacts graduation, prospects

for college and employment.

“My job has gone from making doctors and

researchers to trying to create community

contributors, people who won’t be on food stamps,

who will be adding to the economic base and not

taking from it,” said

Jenny Kaiser

, a GCU alumna

and Alhambra math teacher for 25 years.

Coria’s job is to improve that trajectory. A

naturalized citizen from Mexico, he became

principal in 2011. At that time, Alhambra was a

“D” school by Arizona Department of Education

standards, and its sophomores had performed

worse on the AIMS test, which measures student

achievement, than did the average Arizona

10

th

-grader.

“It felt D-ish because kids were falling through the

cracks, and there was nothing in place to help

them,” Kaiser said. “There were so many discipline

problems and absences, and there were low-

performing kids who weren’t in math or reading

classes at all.”

The gap in test scores still exists today, according

to 2013 data, but it is closing, and Alhambra now is

Claudio Coria, Alhambra’s principal since 2011

and a naturalized citizen from Mexico, has set

the bar high for the school, saying, “We can’t be

mediocre.” Photo by Darryl Webb