(Editor's note: This story is from the August 2016 issue of GCU Magazine. To view the digital version of the magazine, click here.)

By Rick Vacek

GCU Magazine

The basketball legacies of Gary Ernst and J.C. Helton aren’t just linked by their coaching statistics. That’s merely a good place to start.

Ernst has won 860 games, more than any high school coach in Arizona history.

Helton retired with 847 victories, more than any middle school coach in Arizona history.

So, yes, both have sustained excellence on their legacy ledgers. But they have so much more in common. Perseverance. Passion for fundamentals, teamwork and chemistry. High basketball IQ. An unabashed love of the game. Great old stories to tell.

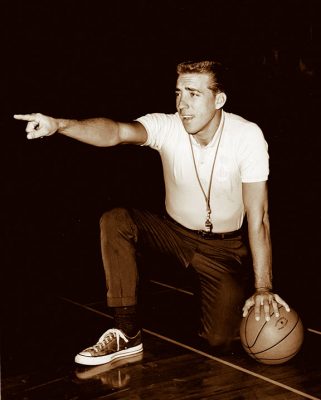

Oh, and one other thing: Both played basketball at Grand Canyon, for coach Ben Lindsey when he was starting out toward winning 317 games, the most in school history. One coach begets two more, and they combine for 2,024 victories. Think it’s just a coincidence? They don’t think so, either.

“I knew when they went into coaching that they were going to make good coaches,” Lindsey said. “That competitive spirit carried over into their coaching. They both worked very hard. I’m proud of them.”

Both former players speak in equally glowing terms about their old coach, and Helton’s relationship with Lindsey goes beyond his playing days — he later served as his assistant coach for four years and used to live across the street from him. But how that came to be is such an incredible story, to this day Helton shakes his head in wonder as he retells it.

Hoosier hysteria

Basketball was invented in Springfield, Mass., by Dr. James Naismith. But people in Indiana will tell you they perfected it.

Helton is a big believer in that mystique. He played basketball at tiny Austin High School for coach Ray Green, a member of the Indiana Basketball Hall of Fame and the father of Steve Green, coach Bobby Knight’s first recruit at Indiana University.

“We bled basketball,” Helton said. “We were dead serious about the game.”

After a stint in junior college he found himself in a lucrative but unfulfilling factory job, but one day he saw in the newspaper that a local player had gotten a scholarship to New Mexico Highlands University. Helton told his buddy Bill Sullivan about it, and they hatched a plan: They were going to drive there and see if they could get scholarships, too.

“We left on June 1, 1965,” Helton said. “Hopped in his 1949 Rambler and we headed west. We’d never been farther west than Vincennes, Indiana. Had no idea where we were going — we just took off. And we get farther west and I’m looking at all the desert cactus and saying, ‘Oh my God, what are we getting into?’”

They got to New Mexico Highlands and learned that the coach was on a recruiting trip … in Indiana, about 20 minutes from where they lived. Try Western New Mexico University, they were told.

They got to Western New Mexico … and the coach didn’t have any available scholarships. Try Grand Canyon College in Phoenix, he said. They got to Phoenix and called Grand Canyon, but Lindsey, who had just been hired, wasn’t there. They got his home phone number. He was playing golf. Still not giving up, they called back in the evening. Bingo. Lindsey told them to come to the gym the next morning for a tryout.

When they drove down 35th Avenue in the morning, they went right past Isaac Middle School, where Helton later would win all those games as a coach and where the gymnasium is now named after him. The tryout went well — “We held our own,” said Helton, ever the competitor — and Lindsey offered them scholarships, right on the spot.

“I knew Indiana was a good basketball state,” Lindsey said. “They looked good in the tryout.” Both were in Phoenix to stay. Helton’s teams at Isaac won six state championships and 10 Basketball Congress International titles, and his players included Darren Woodson, who also played football and became a star safety for the Dallas Cowboys, and Gerald Brown, who later played for the Phoenix Suns. A picture of Woodson hangs on the wall of Helton’s study — “To the best coach in America,” the inscription reads. Sullivan became a school administrator and was superintendent of the Cartwright School District in Phoenix. All because of a road trip that no travel agent could ever dream up.

Chemistry lesson

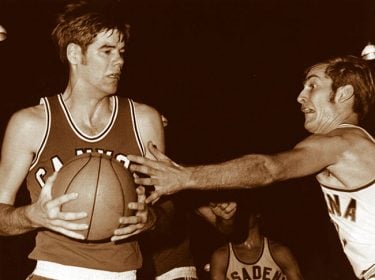

Ernst’s path to Grand Canyon was more conventional — he was playing at Mesa Community College and then transferred over with several teammates. But he feels just as indebted for what playing ball at Grand Canyon did for his career.

“We were very, very close-knit,” he said. “It was one of the things I learned that helped me there at that time – how important chemistry was, how important kids getting along was. That’s always been a stress I’ve had in coaching is trying to make sure that I create that chemistry.”

He clearly has succeeded. Ernst’s teams at Mountain View High School in Mesa have won eight state championships, and Helton got to see his fellow Lope’s coaching acumen firsthand — he was a referee for years (often doing games with Sullivan) and officiated many of Ernst’s games.

“Gary is a good fundamental coach,” Helton said. “Very good disciplinarian. Very structured. Well organized. Team basketball. Really, really good coach. I respect Gary a lot.”

Ernst doesn’t have an Indiana background — he grew up in Farmington, N.M. — but his roots also are deeply entrenched in fundamentals. Some coaches win simply because they have great players; Ernst wins because he has made a habit of turning good players into great teams.

“We tell the kids that this coaching staff is old school,” he said. “We really push the fundamentals, offensively and defensively. I think chemistry is huge. Our parents provide dinner once a week for our players at somebody else’s house, and I just think that has a huge impact on our chemistry. You don’t have to have the most talent as long as the kids appreciate each other and value each other.”

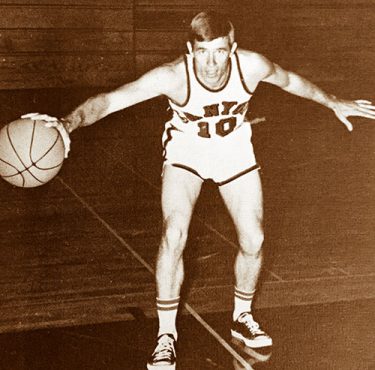

Ernst, who played on the 1969-70 Grand Canyon team that became the first in school history to go to the NAIA district playoffs, and Helton both speak fondly of playing in the old North Gym. “It was a little crackerbox, but it was full,” Ernst said. “It was a great home court.” And they also take great pride in what the University is doing today.

“It probably means more now than it did back then — not to me, but to other people,” Ernst said. “It has more relevance. To see the growth of the school is pretty prideful. This is my school.”

Helton’s love of GCU is so deep, it’s downright dangerous. He lives only a few blocks from campus and drives past the University regularly … much to the dismay of his family.

“Every time I go by there, I’m looking to see what’s going on, I’m so interested,” he said. “They say, ‘Dad, you’re going to wreck. You need to let somebody else drive when you go by this school because all you want to do is gawk.’”

Maybe the best legacy of a coach is inspiring others to walk in the same footsteps. Helton did exactly that for Dan Nichols, now an associate athletic director at GCU. Nichols wasn’t sure if coaching was for him until Helton convinced him to be his successor at Isaac, and Nichols went on to become the head coach at GCU.

“I owe a lot to J.C. He’s one of the two biggest mentors I’ve had in my life,” said Nichols, who still has lunch with Helton regularly. “Every guy, whether you have a father you can talk to or you don’t, you need a couple people in your life that will turn things for you. J.C. got me to realize that coaching probably was something I should be doing.”

There no doubt are a lot of former players who would say the same thing about both Ernst and Helton. That’s what it’s all about. And that’s how good legacies never end.

Contact Rick Vacek at (602) 639-8203 or [email protected].