Story and photos by Laurie Merrill

GCU News Bureau

If concentration level is equal to noise level in a College of Science, Engineering and Technology classroom at Grand Canyon University, what is the net outcome?

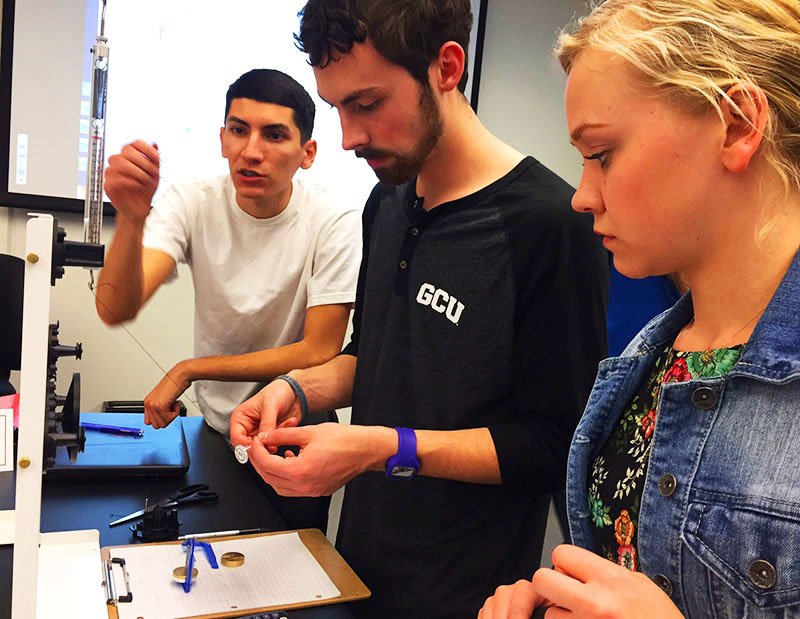

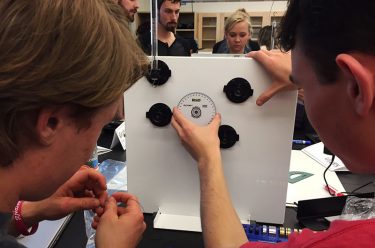

While that obviously is not a real engineering question, the students in CSET professor Dina Higgins’ class spoke animatedly as they collaborated during a recent lab on “vector addition and resultant forces.”

And if they were to answer the question, they likely would say the new education style equals better understanding.

“I love it,” sophomore Vi Tran said. “This is the best way to learn.”

Tran and other fourth-semester engineering students are the first in GCU’s two-year-old engineering program to enroll in an ESG-360 Statics and Dynamics & Lab.

It is one of the first classes to be held in the east-west wing of Building 1, GCU’s state-of-the-art engineering structure that opened earlier this month. And like other engineering classes under development, it is taught in a style that stresses hands-on experiments and de-emphasizes the long-lecture format.

“Hands-on learning is the best way to learn concepts in engineering,” said Greg Bullock, an instructional assistant. “It ensures that they understand the ideas.”

During the first minutes of class, instructors introduce a concept, principle or fact. During the next 10-15 minutes, students apply it in a “mini-lab.” This is repeated throughout the class.

Higgins designed what she calls the “& Lab” portion of the curriculum, about 40 activities that each meet the objective of a specific topic.

“There is something every day, for the most part,” she said. “I will find out whether it works or not, especially when it comes to the timing.”

The first day was a success, she said, and Day 2 went well, too.

Student teams of two and three converged around statics boards on elevated tables. They used spring scales, force wheels, pulleys and strings to determine the “resultant force” and the “rectangular components, both magnitude and direction of a resultant force.”

What does that mean?

“We are practicing vector addition using different techniques,” said sophomore Kaitlyn Raney, partnered with Graham Guske, also a sophomore, as they were looping string through pulleys.

Vectors are mathematical constructs that represent physical forces, velocities and displacements. For example, a vector can represent the speed and direction of a moving car — but it is not the velocity of the car.

To make it even clearer, Higgins said such engineering know-how can be used, for example, to stabilize cell towers with cables.

“We need to know what the forces are on each cable to know whether it can withstand a wind,” Higgins said.

The information also is helpful in assessing what size cable is needed in a crane to pick up objects of varying weights, Bullock said.

“You have to size the cables appropriately so they don’t fail,” he said.

As the first team successfully created a static system with vectors exactly opposite each other, Raney and Guske were backtracking and retying string. They were enjoying every hands-on minute.

“I learn better from labs than from lectures,” Guske said. “It makes more sense when you physically see and touch what you are learning.”

Contact Laurie Merrill at (602) 639-6511 or [email protected].