By Mike Kilen

GCU News Bureau

Shots fired at Foss High School.

Jesse Villahermosa heard the call over his squad car radio in 2007. It was Ben’s school, his son. He floored it to 110 miles per hour. He felt like throwing up. He dialed. One ring … two rings.

“The longest three rings of my life,” he said. “He picks up.

“I hear, huffff, huffff, huffff …

“He is running.”

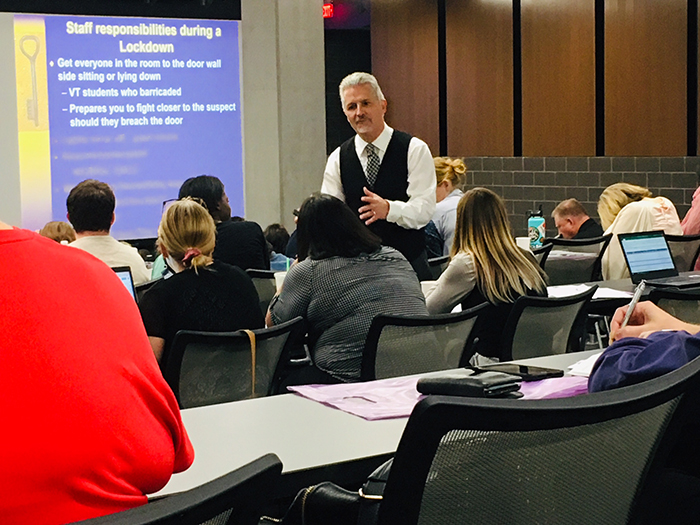

The crowd of area school teachers and administrators leaned forward Thursday to listen to the Villahermosa’s harrowing story at “Making TIES: School Safety” at Grand Canyon University, a one-day seminar organized by Canyon Professional Development.

Ironically, Villahermosa had been a county SWAT team for more than 25 years in Washington State and had trained people across the country on how to survive the violent tragedies of our times – mass shootings. (There have been 283 in the U.S. so far this year, on pace to break the 2016 record of 383.) Now it was happening to his own son.

“I’m running, Dad!” he told him. “There was a shooting at the school.”

“Keep running, son.”

Villahermosa, of Crisis Reality Training, Inc., told the group that the last thing he heard his son say before he hung up was, “Everybody keep running!”

His son survived, using advice his dad has spread nationally: Run. It’s one basic tactic, often not used, of several that refute “duck and cover,” which hasn’t worked since it came into play during the Cold War nuclear bomb drills of the 1950s.

He has seen enough police footage of events to know. The victims often are found crouched under their desks.

Since the Columbine shootings of 20 years ago, educators have long instituted lethal threat plans and shooter drills and have watched videos. It’s a part of life now, like lesson plans. Yet myths persist, and tactics vary.

The first myth is that it can be prevented by identifying a potential shooter. A bullied student? That includes 85% of students, so it’s hard to pinpoint. Mentally ill? Less than 3% of mass shootings are attributed to people with mental illness, he said.

One statistic is relevant – 97% of shooters are male.

“We’ve got a male violence problem in this country, but we don’t want to deal with that,” he said.

“You’ve got to stop thinking that we know this kid will be a shooter and this kid won’t. We have to teach how to mitigate it when it happens.”

The key is getting students trained.

“Kids leave my classes jacked up. Why? Because we are finally making them part of the solution,” he said. “Make kids part of the plan.”

His training includes several steps that don’t rely on administrative rules that too often hinder survival. You can’t expect a kid under fire to remember to run to the northwest corner of the football field. You can’t make teachers call off a roll call during an active threat when one of the keys is staying quiet.

“We are telling people what to do based on accountability. During an active threat, those policies and procedures don’t apply anymore,” he said.

One teacher wouldn’t open a locked door for yelling students trying to flee a shooter. One teacher lined students up single file along the school property perimeter with a shooter inside because she wasn’t supposed to leave the grounds.

“They were thinking civilly in an uncivil event,” he said.

Michael Guerra, Principal of St. Matthew Catholic School in Phoenix, said his school has largely followed much of the advice he heard at the seminar, empowering students to voice their concerns and using common-sense approaches.

“We are in a crime-ridden area, so we have been more flexible,” he said.

He said the openness with students stopped one potential situation when a student told administration about a plan to harm a teacher.

The seminar was part of GCU’s outreach to supply training and tools to area schools, said Carol Lippert, Executive Director of K12 Outreach and Educational Development. “We need to keep our kids safe, and he knows the best information to do that.”

Villahermosa preaches several tactics, though most are familiar with just three -- “run, hide and fight.”

Lockdowns work. They've proved to have the highest survival rate. He suggests opening the classroom door, pulling in who you can, locking or barricading the door and huddling low along the wall-side door. Studies of prior shootings show shooters who can’t quickly see victims and fire will move on. That’s why window drapes or blinds are important, too. Pull them.

Running works, as his son proved, especially if you’re near the killer. Even trained law enforcement has low rates of hitting running targets not going in a straight line, another reason not to arm teachers, he said. Crawling, hiding and playing dead all can work if the threat is upon you.

If nothing else is left to do, fight.

It seems like instinct, but often the survival drills have led to passive victims who end up like sitting ducks. The students can be trained how to follow some basic steps and improvise.

Bash the shooter in the head, stab them with something sharp, run. Survive.

“I like the realistic approach,” said Kevin Cashatt, an administrator at Glendale Union High School in charge of school safety. “Let’s have reality and not sugarcoat it.”

Villahermosa asked this of the school staffs: “Have you given them permission to fight for their lives?”

One of the best ways to avoid active shooter situations, he concluded, is to create relationships with the students on your campus.

The rest of the day's seminar was spent on that subject with Dr. Lily DeBlieux, Pendergast Superintendent, discussing the Speak Up, Stand Up, Save A Life program. This event, spearheaded by DeBlieux, is held annually at GCU and focuses on building student leadership skills to empower them to “stand up” for their fellow students.

A final presentation by Lippert showed participants how classroom instructional and disciplinary practices are linked to relationship building.

“We know that when we teach kids how to engage in academic discourse and peer feedback, we are also teaching them how to talk to one another," she said. "This ability to have positive interactions in the classroom will translate to the student’s time outside of the classroom and bring positive interaction to the forefront across the entire campus.”

Grand Canyon University senior writer Mike Kilen can be reached at [email protected] or at 602-639-6764.