Photos by Ralph Freso / Slideshow / Watch

Marcus Doe embraced vengeance.

Few people would question it.

Doe grew up in Liberia, shattered by civil war. He saw the evils of man, the kind parents shield their children from.

When he was 9 years old, his mother was murdered.

Soon afterward, he ran as far away as he could. He and an older brother escaped on a ship and lived in a refugee camp in Ghana.

Other children made fun of him because he was so poor and didn’t have anything. He battled malaria countless times.

“I have head lice. I’m struggling,” he said, recalling that time.

Then he received a letter from one of his brothers.

His father, who served as an assistant director to Liberia’s secret service, was captured and murdered.

So by the time he was 11 years old, he was an orphan.

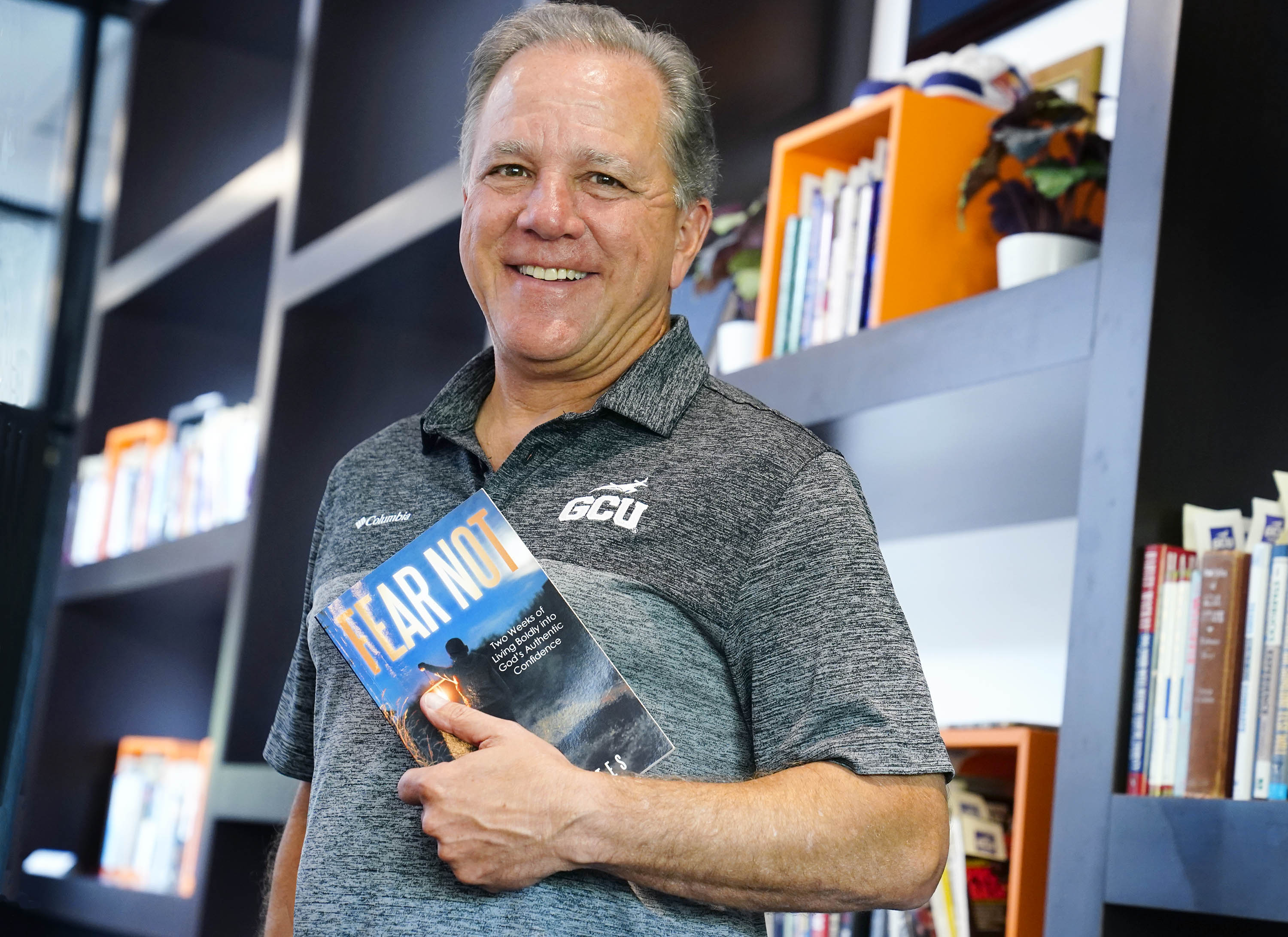

“When I received those letters, something changed in my heart. I became vengeful,” said Doe, a pastor at Redemption Tucson and a first-time speaker at Chapel on Monday on the Grand Canyon University campus. “I told myself at age 12: I’m going to find the man that killed my father and take his life.”

Yet he somehow managed to let vengeance go.

He was in his 20s, he said, when he read Matthew 6:14-15: “If you do not forgive others, the Heavenly Father will not forgive you.”

“It stuck with me … because I was harboring unforgiveness,” he said, and unfolded a parable from Matthew 18:23-25 of a king who wanted to settle his servants’ accounts.

One of those servants owed him 10,000 talents, an unthinkable amount, since one talent was worth about 20 years of a day laborer’s wages.

The slave begged the king, “Be patient with me. I will pay you everything.”

His master had pity on the servant and forgave him the debt.

But when that slave saw a fellow slave who owed him 100 denarii — what would be the equivalent of the daily wage of a day laborer — that same slave who was just forgiven the unpayable debt of 10,000 talents began choking the man who owed him and demanded to be paid.

Other slaves were deeply distressed and reported what happened to their master.

The king told the slave who had no forgiveness in his heart, “You wicked slave, I forgave you all that debt because you begged me. Shouldn’t you also have mercy upon your fellow slave, as I had mercy on you?”

Jesus, in telling this story to Peter, said, “This is how my Heavenly Father will treat each of you unless you forgive your brother or sister from your heart.”

Doe said, “Jesus in this parable is making it clear to us that forgiveness is essential.”

If that parable isn’t powerful enough, Doe turned to a modern story of forgiveness involving the family of Botham Jean. The 26-year-old accountant was murdered in his own apartment by Amber Guyger, an off-duty Dallas police officer who, on Sept. 6, 2018, mistook Jean’s apartment for her own. When she saw him in the apartment, she thought he was a burglar and fatally shot him.

“I was outraged,” Doe said. “Another black man killed.”

But then during her sentencing, when the judge asked if any of the family members wanted to speak, Jean’s brother, Brandt, told Guyger that he had forgiven her and asked the judge if he could embrace her.

“My question was, how did Brandt do that? Where did he get the strength?” asked Doe.

“THAT is Kingdom living. That is living in the world but not of the world. That is a young man who understands what he has received from God vertically, he is extending horizontally to his brothers and sisters.”

Doe said we are living in a world not often guided by forgiveness.

We are a culture, a society, stranded in the wilderness, held hostage by uncompromising people, activists who are angry. Our discourse is driven by anger ... We are bereft of the energy to compromise and to forgive."

Marcus Doe, Redemption Tucson

“We are a culture, a society, stranded in the wilderness, held hostage by uncompromising people, activists who are angry. Our discourse is driven by anger … We are bereft of the energy to compromise and to forgive.”

He added that we are quick to recognize and oppose those who are ideologically, politically or ethnically different than ourselves.

Just look at the movies we love of the good guys — our heroes — pursuing the bad guys who have killed someone they loved and are now seeking revenge.

“We cheer because somewhere within us, we know we can achieve justice in our own hands,” Doe said. “ … We separate justice from forgiveness. Somewhere, justice and forgiveness doesn’t add up.”

Blogger Sabine Birdsong, in a blog entitled “To Hell With Forgiveness,” says as a society we believe forgiveness makes us superior and that if we can’t manage to forgive someone, we are looked down upon. She says forgiveness is a “deeply engrained religious hangover from Christianity,” Doe said, and that forgiveness allows abusers to act without impunity because they can rest assured that they can be forgiven.

“This poses a great question: Must forgiveness and justice oppose each other?” in a society in which we no longer are sheep but have become the wolves.

For Doe, the answer is no.

In 2010, at 31 years old, he returned to Liberia, not for revenge, but to find the people who had murdered his parents and to forgive them.

| Next Chapel (11 a.m. Feb. 27, GCU Arena): |

| Dr. Tim Griffin, University Pastor |

He hadn’t seen his brothers for 20 years. They thought he perished; he thought they perished. They found joy in their reunion.

But it was a simple trip to the barber that really shined a light on his own journey of forgiveness.

The 10 men in the barbershop asked Doe his name, and when he told them what it was, they told him that no one with his last name survived the war, including the dictator who ruled Liberia.

They all stood up, looked at him and asked him, “How did you survive the war?”

All of the men in that barber shop were former child soldiers who would have killed him 20 years ago, and the barber trimming his hair was a former rebel.

They asked him why he came back.

Doe told them, “I came back for people like you. … They weren’t the monsters that I thought they were.

“… I’m sitting in this shop and we’re all crying. These are men who would have gladly taken my life 20 years earlier. It was a beautiful moment. It was a beautiful moment.”

And it reminded him of that Bible passage that encouraged him and changed his heart so many years ago.

“You owed God a debt you could not pay … but there is someone who paid our debt. … We get to live debt-free and death-free forever. We get to live in the Kingdom despite our sins because our debt has been paid by Jesus on the cross.”

As Jesus paid our debts — as our sins have been forgiven — it is essential to do the same for others.

“Somewhere, you receive forgiveness from God, and you should pass it on to people who have done something to you. We can extend forgiveness because we have been forgiven. Forgiveness is key to living in the Kingdom of God. It is OUR key to move on in society as a people.”

Lana Sweeten-Shults, GCU manager of Internal Communications, can be reached at [email protected] or 602-639-7901.

***

Related content:

GCU News: Spring Chapel schedule has feel of familiarity

GCU News: CityServe leader: Move toward those in pain

GCU News: No stopping God’s work, Mueller tells Chapel

GCU News: Chapel speaker: What will you do with your failures?

GCU News: Pastor’s Chapel message: Listen to the right voice