Story by Doug Carroll

Photos by Darryl Webb

GCU News Bureau

As the students, faculty and staff of Grand Canyon University adjourned for Christmas break near the end of 2003, few of them had much knowledge of the financial health of the sleepy, west Phoenix campus where they studied, taught and worked. They were in the dark, and that was not a bad place to be.

Like many private institutions of higher education, Grand Canyon had endured its share of struggles since its humble beginnings in 1949, after three Baptist pastors each had plunked down a silver dollar to start Grand Canyon College in Prescott. Lacking either the taxpayer support of public universities or the substantial donor base of successful private colleges, the school depended primarily on tuition-paying students, of whom there were about 1,500 on campus and a similar number taking classes online in 2003.

Budgetary surgery was a way of life.

“Every few years, there was a financial crisis,” recalls Dr. Charles Maxson, then in his 20th year on the faculty at Grand Canyon. “That’s how it was, and how most small colleges still are.”

In 1997, the University’s lenders had pressured the governing board for a change in leadership. After a brief restructuring, the banks backed off, and Grand Canyon wobbled on down the road. Athletes still competed, future nurses and teachers still graduated, and instructors and staffers somehow never missed a paycheck.

However, like a gravely ill hospital patient, the University’s internal organs were starting to shut down. Some of those who were trained in making health assessments kept a wary eye on the heart monitor — their pay.

“I was making less than when I started,” says Dr. Cheryl Roat, who had been with Grand Canyon’s College of Nursing for 17 years, recalling an increase in her teaching load paired with a 6 percent reduction in salary. “That was an indication of problems. We knew there were issues.”

Those issues were enormous, and they added up to an inarguable conclusion by the University’s board and the school’s president at the time, Dr. Gil Stafford.

Grand Canyon University was in intensive care — on life support, even — and its prognosis was grim.

“Grand Canyon, from its first day, was on thin ice,” says Stafford, who had put in 20 years at the school, including several as its highly successful baseball coach, before becoming president in 2000. “The institution was always in dire straits.”

The vital signs were much worse than anyone on campus knew, with the exception of Stafford and a few administrators and deans. The school was losing $16 million a year while taking in only $4 million in revenues. Its endowment was a paltry $4 million, and potential donors had disappeared over the collapse of the fraudulent Baptist Foundation of Arizona in 1999. The bleak situation had caught the attention of federal regulators, who were concerned about Grand Canyon’s ability to meet its financial obligations.

“We had no idea things were that bad,” says Keith Baker, then GCU’s associate director of athletics. “We were told that some consultants were coming on campus. They were basically looking under the hood of the car and getting ready to buy it.

“Most of us didn’t know what that meant. How do you buy a university?”

December 2003: The art of a deal

Brent Richardson, the entrepreneurial son of a K-12 school superintendent, had an idea of how it might be done. Richardson and his brother, Chris, were part of a small group of investors, Significant Education LLC, that spent the tail end of 2003 sizing up GCU.

Richardson, then 41, took a shine to Grand Canyon, seeing possibilities where others (including his innovator father) saw only problems. He already had been successful at marrying technology to education, a concept that in its early days was like striking oil. He and Chris had started Masters Online, an online curriculum company, and had learned of GCU’s struggles while doing work with that company for the University’s College of Education.

The rescue operation came with considerable risk, but the Richardsons trafficked in risk. Although GCU’s $20 million debt wasn’t sufficiently scary, it came close.

“When you’re an entrepreneur, you go by your gut on a lot of things, and you build around that,” Richardson says. “We were looking for schools to do this with. When I walked the grounds for the first time, I had the feeling we could really build something that hadn’t been done here, a model for what a traditional university could be.”

In early December of 2003, the board agreed to sell, but only if an agreement could be struck by Jan. 5, 2004, the Monday when classes resumed. Otherwise, the school would close. The investors, who had yet to see even one document from GCU, went into hurry-up mode, hunkering down at a local hotel and working around the clock, even on Christmas Day, to hammer out a deal.

Then, right on time, came the Jan. 5 bombshell: In a one-page memo, Stafford officially announced his resignation as president to enter the Episcopalian priesthood, adding that “a very highly qualified educational management corporation” would oversee the school for an interim period. In a second memo, this one from board chairman Don Pewitt, the period was defined as 30 days. The outside firm, Pewitt said, would “provide money, management and marketing to stabilize the school and position GCU for significant long-term success.”

American history was being made on three fronts: higher education, business and religion. Grand Canyon would become the first regionally accredited nonprofit university to convert to for-profit status. It also would become the first for-profit Christian college, although it had dropped its Southern Baptist Convention affiliation in 2000.

A month later, the structure of the new GCU became clear. A board of trustees would oversee the nonprofit side of the University, the Canyon Institute for Advanced Studies (today’s GCU Foundation). And a board of directors under Significant Education would administer the for-profit side, owning the accreditation, programs and lease on the 100-acre campus. The acquisition of the accreditation was crucial.

The Richardsons had their school now, and Brent Richardson officially became Grand Canyon’s chief executive officer. On his first day on campus as CEO, a hot-air balloon landed near the main entrance and he saw a woman break her leg while chasing after a dog.

The adventure was only beginning.

“I thought, ‘What have I gotten myself into?’” Richardson says.

2004-08: Pursuing progress

Although boosting online enrollment was the key to shoring up the University’s shaky finances, Richardson met with students, faculty and staff and made two things clear, to their relief: The new management team would not abandon either the traditional campus or GCU’s Christian heritage.

Despite being a money loser, the athletic program was deemed worthy of retention, as a way of maintaining a sense of normalcy. Baker was asked to take over as interim director of athletics, and he remembers a conversation with Richardson in early 2004.

“I’m risking everything I’ve got on this,” Richardson told him, “and I’m not sure if this will work. But if it does, it will really be a fun place to work.”

Athletics had its own mess to deal with. GCU already had decided to leave NCAA Division II and return to its original NAIA membership, and NAIA schedules for several sports had been finalized. But the NAIA, now skeptical of the school’s acquisition, dumped GCU, citing a bylaw (since changed) prohibiting the admission of for-profit institutions.

Ironically, the NCAA had no such problem with GCU, saying there was nothing to keep it from being in Division II. Nevertheless, presidents of institutions in the California Collegiate Athletic Association refused to consider the University’s petition to rejoin the league, so eventually the fledgling Pacific West Conference agreed to give the Antelopes a D-II home.

“We were an anomaly, and people didn’t know how to take us,” Baker says.

That was true even on campus. Dr. James Helfers, then dean of the College of Liberal Arts, remembers a first year under the new management that was “both unnerving and exciting.” But by the end of 2004, when Richardson awarded Christmas bonuses on the front lawn of campus and many were moved to tears by the gesture, believers outnumbered doubters.

“Everybody was doing extra, going the extra mile, and Brent had told them he’d pay them back,” says Faith Weese, then in public relations for the school. “They just trusted him so much.”

It wasn’t perfect. Tensions rose in May of 2005, when the University decided not to renew the contracts of 17 full-time faculty members, five of whom had tenure. A partnership on a teen center with rock star Alice Cooper didn’t pan out after receiving national media coverage in 2006. Students sometimes left the University bitter and disillusioned when treasured programs, such as music and theatre, were shuttered to slash costs.

“To see the music program crumble was devastating,” says Amanda (Gardner) Mutai, who left in 2005 but returned in 2010 when the arts were reinstated, graduating last December.

After the third year under the new regime, GCU was in the black. In 2008, it had a robust enrollment of 12,000 online but only 1,000 students on campus. Its future wasn’t yet secure, and the stage was set for the next big thing.

2009-13: Booming and building

Unlike Brent Richardson, Brian Mueller was not a natural-born entrepreneur. Throughout high school and college, all he wanted to be was a teacher and a basketball coach — and that’s what he was, at Christian high schools and colleges, until he decided to move to Arizona with his young family to pursue a doctoral degree from Arizona State University.

Mueller and his wife, Paula, had three children with a fourth on the way and struggled to make ends meet while living with a relative. He was teaching philosophy at ASU for $5,000 a semester and driving a broken-down car. He realized that something had to change, and in 1987 he found work at the University of Phoenix as an enrollment counselor.

Something did change — and the arc of Mueller’s career along with it. The University of Phoenix tapped into a growing demand for working-adult education as no one had before. Mueller moved up through the ranks of its parent company, the Apollo Group, in a career of 20-plus years, eventually running the company’s online operations and later becoming president.

Although he never had taken a business course, he grasped how higher education and business could be fused. The Richardsons had taken notice, and they invited Mueller and Dr. Stan Meyer, who also had experience in Christian education, to a meeting at a cigar store on 44th Street in Phoenix to discuss Grand Canyon and the University’s next step: taking the company public.

After two more meetings involving other representatives of GCU, Mueller was beyond intrigued.

“Sounds to me you’re ready to say yes to this,” Brent Richardson said to him.

Mueller recognized a unique opportunity for a private Christian university with an investment model of funding. Grand Canyon was positioned to offer a faith-based college education at low cost to students and no expense to taxpayers while providing a reasonable return to investors. The Richardsons had saved the school, and now he could be the architect of its renaissance, with a goal of building the “city on a hill” of which Christ spoke in the Sermon on the Mount.

This was more than higher education for him. This was a higher calling.

“I now understood God’s purpose for my life,” Mueller says.

He joined GCU as its CEO in July of 2008, bringing with him Meyer as chief operating officer and Dan Bachus as chief financial officer. An initial public offering in November by Grand Canyon University Inc. — traded on the Nasdaq exchange as LOPE — resulted in an infusion of $230 million.

“The IPO was the smartest thing,” Maxson says. “It got us square (financially) and gave us extra money to keep going.”

A dizzying, five-year transformation of campus was under way. The funds enabled a massive renovation and expansion, ushering in new classroom buildings and labs, residence halls, a food court, a Student Recreation Center and GCU Arena. The arts program was restored, and athletics began a transition to NCAA Division I. Community outreach efforts intensified.

“Brian came in gently,” Baker recalls. “He didn’t puff himself up. He was a work-ethic guy who got to know the people and the operation.”

Mueller says the biggest challenge was “putting in place what was necessary to scale this in a high-quality way,” along with convincing the Christian community of the merits of the investment-supported model. For two years, he says, the work was “very, very hard.”

Those who had been along for the entire ride, who had been through so many twists and turns, could only marvel at what was happening. Many of them saw God’s hand on the wheel. How else to explain such a miracle?

“When Brian was brought on, that was the true birth of the Grand Canyon we have now,” Helfers says, “and the rebirth of us as a Christian university. It put us back on the path that I know the board of trustees wanted when we went for-profit in the first place. This is a grand experiment in what it means to be a for-profit, Christian institution.

“Now I can say I know why I was supposed to stay here. What energizes me is the way we are putting together lives of faith and learning.”

Roat, who was first attracted to the school for its Christian heritage, says she never considered in 2004 that GCU might fail.

“When I knew there would still be a Christian focus, I trusted,” she says. “I’m glad I stuck it out. I believe in the University. If anything, the Christian and community focuses have improved.

“I feel like I belong to a family here.”

2014 and beyond

What will the next 10 years hold for a healthy Grand Canyon University, the little school that refused to die?

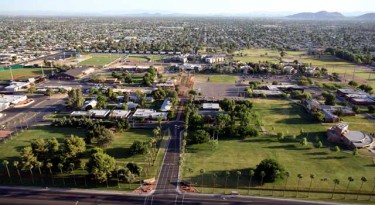

Mueller, 60, now GCU’s president as well as its CEO, is thinking about that — and plans to be around for it. Technology programs are ready to launch in the fall, engineering programs next year. A campus in Mesa also will open in 2015. A K-12 partnership that already includes nearby Alhambra and Maryvale high schools is seen as part of an economic catalyst for west Phoenix.

By 2025, GCU could have 30,000 traditional students between its Phoenix and Mesa campuses, plus an additional 100,000 (mostly postgraduates) studying online.

“This is mission-oriented,” Mueller says of the road ahead. “I could get offered the job to coach the New York Knicks or UCLA Bruins, and I’d turn it down. This is exactly what I want to do.”

Stafford, who had an up-close view of the worst of times, likes what he sees from GCU and says the school’s heartbeat, faint for so long, is now strong.

“I’m extraordinarily proud of all the things that have made Grand Canyon what it is today,” he says. “Brian Mueller is a wonderful leader. I’m thankful to God that Grand Canyon is alive and well and meeting the needs of the community as only it can do.”

Contact Doug Carroll at 639.8011 or [email protected].