By Michael Ferraresi

GCU News Bureau

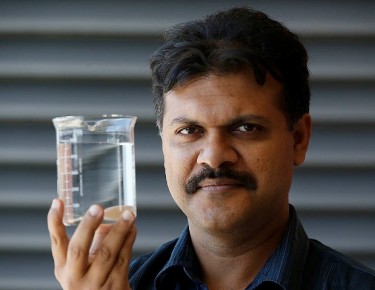

The tap water looks clear. It might even taste decent. But Dr. Randhir Deo worries about hidden trace contaminants.

If antibiotics, antidepressants, synthetic estrogens and other drugs find their way into our surface water, then humans face the chance of ingesting those chemicals either directly or indirectly through rivers, lakes and oceans. Water system, both natural and man-made, blend together — and the average person rarely sees that free-flow of material underground.

In an article published earlier this month in the journal Current Environmental Health Reports, Deo, a Grand Canyon University assistant professor of chemistry, cited a compilation of environmental science research that showed 93 pharmaceutical drugs reported in U.S. surface water. The April report marked the latest in Deo’s commitment to reporting on environmental science issues, particularly about contamination of built and natural water systems.

Oftentimes, trace amounts of those drugs end up in the system after people flush their unwanted or expired pills down the toilet. Recent research shows that humans face a low exposure to pharmaceutical drugs in drinking water, although Deo said much needs to be studied about how Americans dispose of their drugs, how governments, universities and other schools educate the community about drug contamination, and how waste water treatment plants handle tainted water.

“Waste water treatment plants were not necessarily built to degrade those complex chemicals like pharmaceuticals coming into the system,” said Deo, a native of Fiji who has taught in GCU’s College of Arts and Sciences for more than two years.

If those chemicals get through to our homes, and into our bodies, what’s the impact? Deo said it’s an issue that future generations of scientists undoubtedly will focus on as the availability of water dwindles. If contaminants get into fish, as Deo pointed out in his articles, food systems are impacted and humans face exposure on that level, too. Scientists have noticed traces of human antidepressants in bull sharks in Florida and chemicals from household cleaners in wild bottlenose dolphins, for example.

Also, chemicals that pass through humans as waste, and end up as bio-solids in the earth, can end up back in the drinking water. What starts on land can end up in rivers or lakes and back at our homes eventually.

“It’s something to be concerned about as far as the long-term effects,” Deo said. “We need to be actively monitoring what’s coming out of those plants and find a sustainable solution.”

“Unless there’s a catastrophe, there’s never an elevated focus,” he said. “But we should not ignore it. The scarcity of water, that issue — it’s not going away.”

The U.S. Department of Justice established April 26 as a national drug take-back day. This Saturday, residents can drop off their unwanted prescription drugs at the Phoenix Police Cactus Park Precinct, 12220 N. 39th Ave., from 10 a.m. to noon. Or you can search for the location nearest you via the DOJ’s Office of Diversion Control website.

The Arizona Department of Environmental Quality urges residents to follow federal guidelines to prevent pollution by using secure drop-off locations.

Deo also addressed the issue of pharmaceuticals in built and natural water environments in an article he co-authored with ASU's Dr. Rolf Halden for the peer-reviewed journal Water last year. In it, he claimed pharmaceuticals in the aquatic environment raise concerns over inadvertent exposures and potential health risks.

He wrote that the “number and concentrations of new and existing pharmaceuticals in the water environment are destined to increase” due to increased drug consumption, an aging population and routine “flushing” of unused prescription drugs into the water system.

Deo earned his Ph.D. in chemistry from New Mexico State University in 2005 before conducting post-doctoral research at Arizona State University’s Biodesign Institute. He discovered his passion for teaching at the University of Guam, where he served as a professor in 2010-2011 prior to joining GCU.

Mark Wireman, assistant dean for College of Arts and Sciences, said that Deo has the ability to make highly technical scientific issues understandable to students. With issues such as water contamination, students can see how chemistry is applied to understanding the impact of science in the real world.

Wireman said CAS professors such as Deo have a commitment to pushing for responsible stewardship of the environment. As more students understand issues such as the effects of drugs in water systems, they will be more prepared to address those issues in their careers as doctors and in other health care professions.

“If we can plant the seed with our pre-med students now, when that trend grows … our doctors are already ahead of the game,” Wireman said.

Deo said studying the issue of contaminants such as pharmaceuticals in water systems requires a multifaceted approach. Research is only one part of finding solutions. He said public education campaigns also are essential to restrict flushing of drugs.

Tracking the impact of hospital disposal of drugs, chemical manufacturer pollution and cleanup strategies are among the trends that Deo said he hopes to write more about in peer-reviewed journal articles.

Getting GCU students involved also is a clear possibility as more information about water contamination surfaces in mainstream media.

“He’s building a nice niche for himself,” Wireman said. “He’s also talking about the big picture of sustainability. When he talks about it, he gets really excited — perhaps even more than the chemistry concepts he teaches.”

Reach Michael Ferraresi at 639.7030 or [email protected].