If the dream of sending a manned mission to Mars comes to fruition, and rockets and astronauts arrive in orbit around the Red Planet, they will need fuel to transport them in the lander to the surface. Right now, the only options are inefficient, requiring more fuel and less payload.

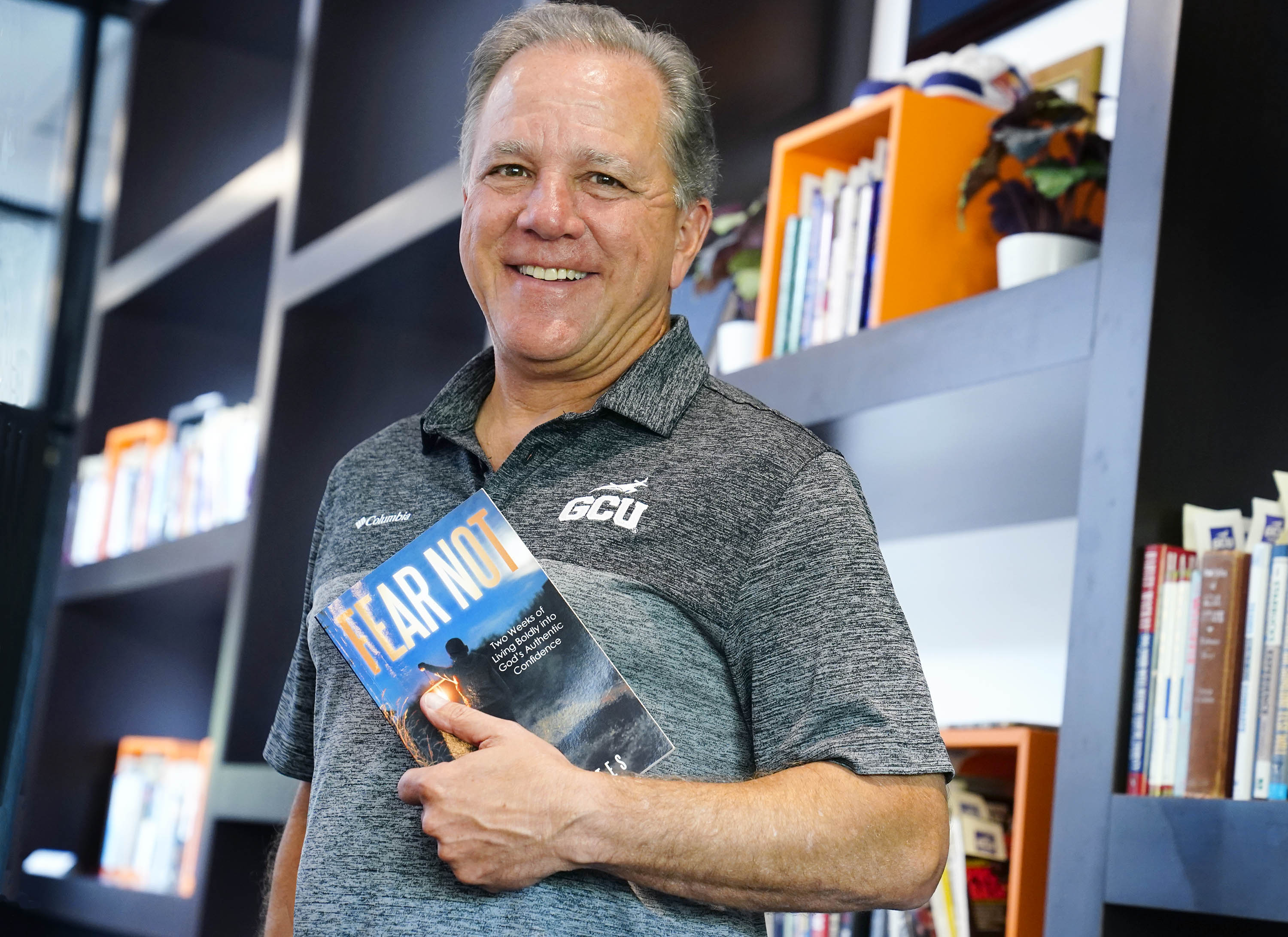

If Grand Canyon University mechanical engineering professor Li Tan and his student scholars succeed, their research, under the umbrella of the university's Canyon Emerging Scholars undergraduate research program, could lead to more efficient rockets.

Their design likely won't be launching Mars rockets. Still, the hope is that it could improve fuel efficiency for planetary landers, military vehicles and devices, model rockets and small satellite launch vehicles.

Tan said his Canyon Emerging Scholars lab group, called the Aerospace Propulsion and Engineering Innovation team, has been studying hybrid rocket design for several years.

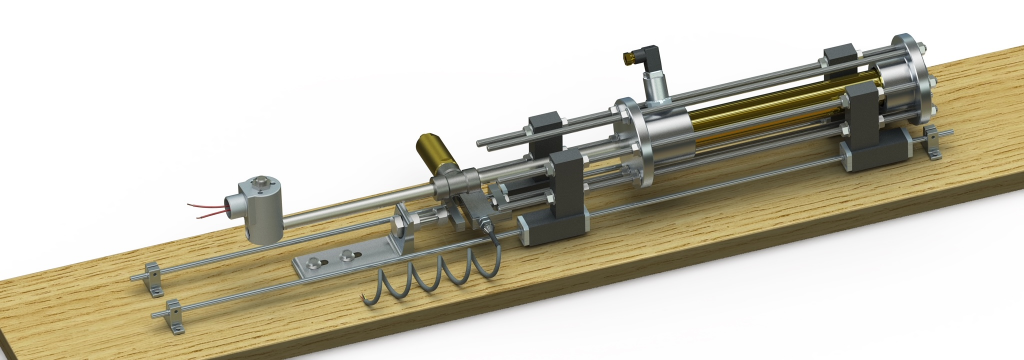

Hybrid rocket engines use both a liquid oxidizer and solid fuel to spark the combustion process. Unlike in solid rocket motors, the oxidizer and solid fuel are stored separately and mixed in a combustion chamber. The design allows for safety through separation. Also, the flow of the oxidizer can be controlled, which allows throttle and restart capabilities, something solid rocket motors lack.

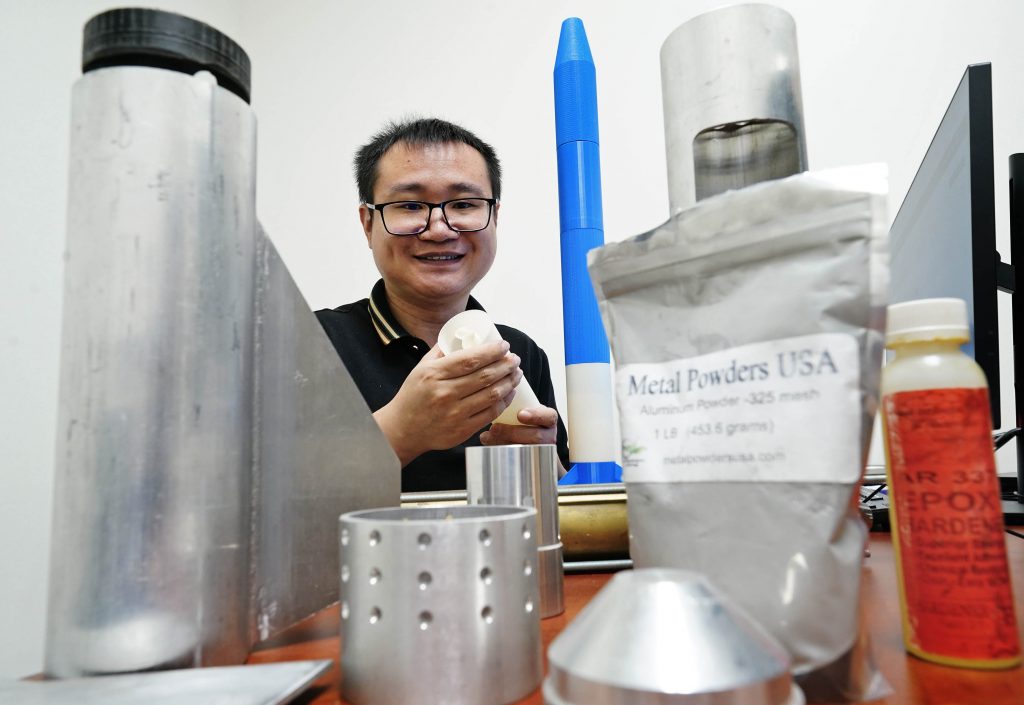

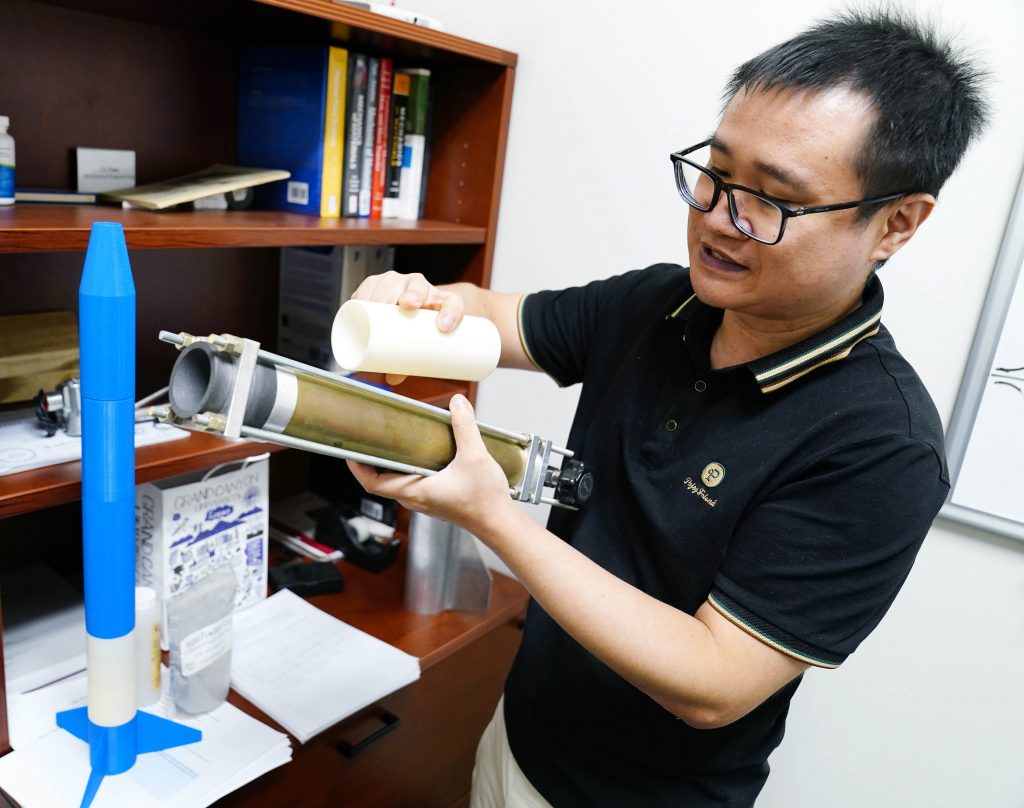

Tan and his team have developed a solid fuel grain prototype, a developmental version of a hybrid rocket engine's solid fuel. The goal is to test different fuel grain geometries and find the shape that produces the optimal power fuel burn.

But for Tan, it isn't his only goal. His mission as an engineer and educator goes beyond building a better rocket engine.

"Our mission is trying to motivate and inspire the young generations about aerospace engineering at GCU," said Tan, who started the project in 2019 with one student, Daniel Hoven.

“At the time, it was just me and a 3D printer,” said Hoven, who's now involved with research and development at aerospace conglomerate Honeywell in Glendale, Arizona.

Tan and Hoven pursued a hybrid rocket motor by burning candle wax – a special paraffin infused with aluminum – and a nitrous oxide oxidizer. Following ignition, the motor builds thrust until the fuel is exhausted.

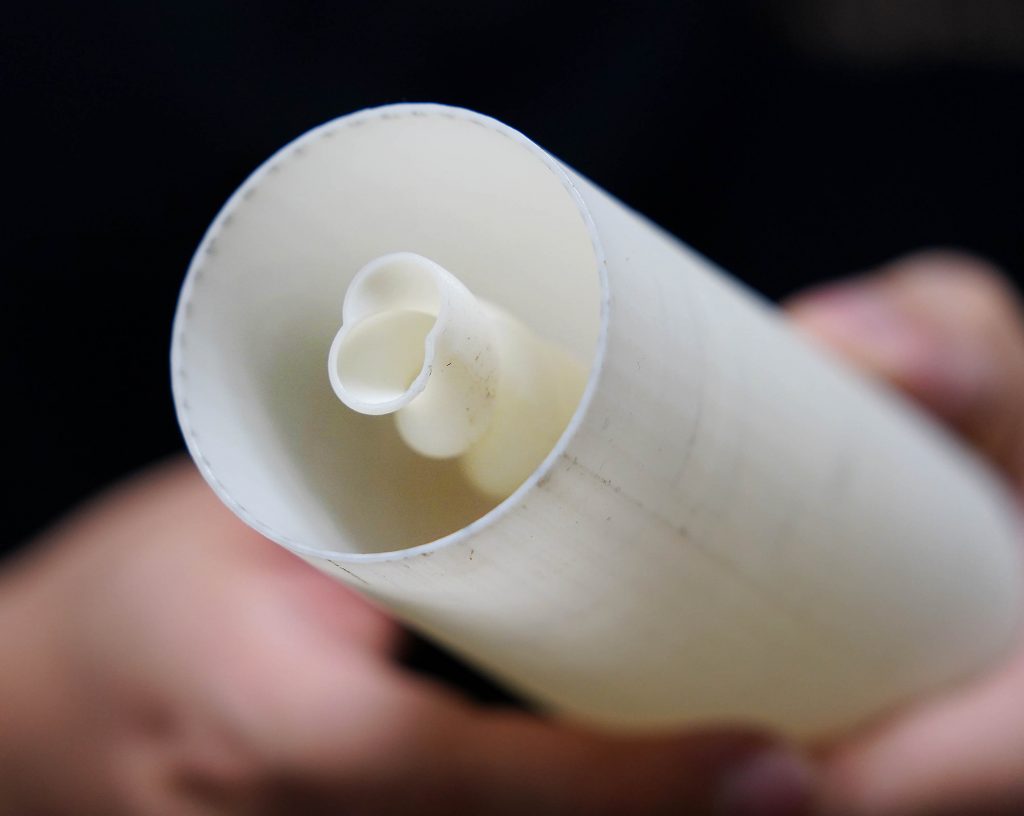

The paraffin is formed into a cylinder with a small hole through the center. The oxidizers are compressed through the hole, and once ignited, the fuel burns from the center of the cylinder to the edges. As the hole increases in size, its efficiency deteriorates.

“The geometry of that (solid) fuel will change the performance of the rocket," Tan said. "So that’s why we would like to know what the optimal geometry is for that solid fuel grain.”

So far, students working with Tan have developed a theoretical geometry that they want to test in a real rocket motor firing.

The project is moving from the theoretical and research stages into building a working rocket motor.

“We had our sample, the prototype for the fuel grain with the shape of a helix. It’s kind of like a DNA shape,” he said. “That’s why when the flow gets through it, it rotates (in a) spiral as they’re burning through the fuel grain. So we think that, theoretically speaking, that is a good shape that can maximize the performance of the process.”

The journey has been challenging for Tan and his research students. In 2019, Hoven joined the project with enthusiasm because he “wanted to build cool hardware.” Despite a rocky start and pandemic-related closures, progress has mainly been theoretical.

“It was completely unthinkable when I first started talking about it because nobody knew how to get approvals for this sort of thing. We didn’t even know who to ask. And the people we asked didn’t know who to ask.”

Hoven turned to the 3D printer to create examples of the hybrid motor that will provide hyper-propulsion for solid-fuel rockets. The problem he and his instructor faced was where to do the build.

That's when the real challenge began – to meet safety protocols to propel the project beyond theory.

“As we are researching rocket building, it has a lot of risk hazards, like fire hazards. Our equipment hasn't gotten approved by the fire department yet.

“We spent about a year trying to get the paperwork approved because once we have the rocket (motor) built, we need a fuel system to supply the liquid oxidizer,” Tan said. “We need a pressurized tank, pipes, valves, high-pressure valves, and then we need a room to store them. I need another open space to test them."

Tan is hoping eventually to launch the rocket and represent GCU in rocketry competitions, such as altitude competitions. But Tan, ultimately, wants to enter more sophisticated events in which the rocket's hyper-propulsion is harnessed and the rocket control features tested. According to Tan, this makes the simple rocket into a guided missile.

Asked about whether all the theory plays out in a career, Hoven said it did for him.

“It was a fantastic way to learn, not just engineering, but science,” he said. “You have to be very targeted in your experimental design. It definitely helped me to figure out how to sell something that was (different than) the type of research that GCU was doing.”

Hoven said that the project helped him in his job with Honeywell, teaching him how to collect, analyze and use data.

“What got me my work at Honeywell was the effort I put into learning control theory and the math and engineering behind it,” he said.

Tan, born in China, studied engineering at Purdue University in West Lafayette, Indiana. It was there that he published his thesis on supersonic flow, which led to his master's degree in aerospace engineering. His work has focused on commercial jet engine blade design and electric motor design for locomotives.

Tan has been an instructor at GCU for more than a decade.

“My program here is trying to set a foundation that inspires more people to get involved with aerospace engineering,” he said. “If we can do that, the next generation will take this rocket and GCU further than we ever imagined.”

Eric Jay Toll can be reached at [email protected].

***

Related content:

GCU News: Student project bridges engineering concepts

GCU News: Starfish operating system just one of the star of research symposium