By Michael Ferraresi

GCU News Bureau

The sounds from the apartment below echo in Magda Herzberger’s mind when she recalls the day she lost her freedom.

There was shouting, and the pounding of the gestapo soldiers’ boots as they forced their way into a neighbor’s home on the first floor. The pounding intensified as the soldiers came upstairs toward her family’s front door. In moments, without warning or time to pack for the journey, they were taken — their world irreversibly altered.

Herzberger was 18 in April 1944 when a group of local gendarmes, Nazi sympathizers at the time, herded her and her parents — and other Jews from their neighborhood in Cluj, Romania — onto trucks bound for a ghetto that served as a staging area for deportations to the death camps. There, millions of Jews and other minorities were systematically murdered during World War II.

For nearly a year, Herzberger struggled to survive the daily routine terrors and psychological torture in three of Adolph Hitler’s concentration camps. She served as a “corpse gatherer,” resisted the lure of suicide, and relied on God for the hope to outlive the Nazi death machine. In her silent moments in the camp as she prayed, she knew in her heart that God could help her make it out alive.

Grand Canyon University students have the opportunity to hear Herzberger’s story at 11:15 a.m. Wednesday in the GCU Library on the fourth floor of the Student Union.

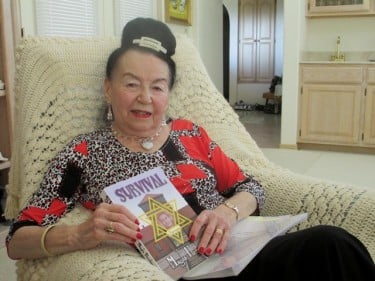

“You’ll see it’s possible to survive unbelievable tragedies in the face of dire circumstances,” said the 88-year-old poet, author and composer of the focus of her GCU visit.

Herzberger's presentation is the first in a series of 2014-15 speakers hosted by the College of Humanities and Social Sciences at GCU, which is one of five universities in the country partnered with the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington to train future teachers to educate students about the Holocaust, including the factors that led to the extermination of 11 million people, including 6 million Jews.

With Herzberger, the University also gets a refresher course in humanity, grace and discovering hope in the darkest of places.

“I think my great trust in God was my source of survival,” she said. “Regardless of what I experienced in the camps, and all those terrible things, I’m still a loving and forgiving person.”

But is that even possible? To love after being kidnapped, tormented, imprisoned and forced to watch mass murder?

It took decades of self-exploration, but Herzberger said forgiveness helped liberate her from the cold, steel, fenced-in confines of the death camps where her father, uncle and others died.

“You have to also carry in your heart forgiveness,” she often reminds people. “If you do that, people live in harmony.”

Romania overwhelmed by hatred

Herzberger's childhood was mostly harmonious. She grew up ice skating on frozen waters in her native Transylvania. She beat out the boys to become a junior fencing champion and enjoyed being around many friends and cousins. Her father, a cultured international businessman, filled their middle-class home with music from his cello, clarinet and violin. As an only child, her Orthodox Jewish parents frequently satisfied her intellectual curiosity and encouraged her to take pride in her studies.

Around 1940, as she was preparing for high school, Hitler’s Nazi empire had begun construction on Auschwitz, and the gestapo started identifying, imprisoning and murdering Jews and other minorities in multiple countries.

Herzberger was one of six Jewish students selected to attend a prestigious high school in Romania, where she faced constant prejudice and harassment from students, teachers and administrators as Nazi anti-Semitism bled through the land. Undeterred, she learned German, French and Latin, and cultivated her dream to go to medical school.

Romania wasn’t always intolerant, Herzberger recalled. At first, she and other students were encouraged by their parents to keep their mouths shut and to tolerate the harassment as best they could. Their education was more important, they were told. But terror rapidly escalated.

As laws changed, and the Nazis seized control of most of Europe, Jews were soon ordered to register with the local government and to affix the yellow star of David (a symbol of shame, to mark the “dirty Jew,” Herzberger explained) to their clothing if they went out in public. They also were forced to turn over radios to the government and forfeit their gold jewelry.

Herzberger's father soon lost his managerial position and the family was forced to move into a humble apartment on a street with other Jewish families faced with similar perils. Eventually, the Romanian government, communities and schools were poisoned by the venom of Nazism. The Jewish children at the prestigious high school — inferior to non-Jewish children, they were told — no longer were welcome.

The Jewish community pleaded with the government to form Jewish schools so children could have somewhere, anywhere, to learn. They got their wish, briefly, and Herzberger said some of her high school instructors were gifted Jewish professors from local universities who’d been kicked off their campuses.

“That was a miracle,” she said. “Otherwise we faced the situation where we wouldn’t be able to study at all.”

The metropolitan, mountainous city of Cluj quickly became foreign to Herzberger. While she found refuge in reading and writing, she and others were terrified to leave their homes.

“You had plenty of anti-Semitic (people) that would beat you up,” she said. “From that time on, we lived in constant fear. We went out only for minimal things. We stayed off the street as much as we could.”

Her father’s tears

The gestapo soldiers who confronted Herzberger and her mother in their home in 1944 wore long, black boots and had helmets with a single cock’s feather standing straight up. They were Hungarian secret police, working with the Nazi “Schutzstaffel,” or SS. By 1944, part of Romania — including Cluj — had fallen under Hungarian control.

When the gestapo began rounding up Jews in Cluj, Herzberger’s neighborhood was one of the first targets.

Herzberger’s father was not home at the time. He was working a clandestine job provided by business friends who didn’t agree with Nazi law. When he returned home on his bike, he found his wife, daughter and neighbors being rounded up onto trucks at gunpoint. He threw down his bike and hopped aboard, nothing but the clothes on his back for the trip to an unknown destination.

After a brief time in the ghetto fashioned from an abandoned factory, where Jews were forced to sleep outside and scrounge for food, the troops began moving people onto train cattle cars to take them to the camps. The train was beyond terrifying, especially since no one knew where they were going. As many as 100 people — men, women and children — were crammed inside with little more than a solitary bucket to use as a toilet. Fearful whispers swirled in the dark as strangers pushed against strangers.

Herzberger remembers worrying about the children. She heard them crying. She saw how small some were, and dreaded the evil they would face once the train stopped.

“For many, that was the road to the grave,” Herzberger said, her voice with its unmistakable Romanian accent trailing off.

But she also worried about her father, to whom she was very close. She had never seen or heard him cry. Yet Herzberger felt his tears falling on her as he huddled over her, before the train stopped at Aushwitz-Birkenau.

She heard him mumble something to the effect of, “We made a big mistake, and now it’s too late.” Other Jews had escaped Romania once the hatred started. Now those in the cattle car were questioning their patience and decision to stay.

As they arrived at the camp, Nazi authorities separated the herd into groups. Essentially, they separated the weak from the strong. And the strong, like Herzberger, were forced to work or die. Pregnant women, invalids and people with disabilities often were sent directly to the gas chambers. The chimneys from the crematoriums belched a constant stench of burning flesh into the air. Herzberger said she felt or witnessed death at every turn.

After Aushwitz-Birkenau — which held more prisoners than any of Hitler’s concentration camps — Herzberger was moved to two other camps, where she dug graves and collected corpses. They had been “cleaned” by prisoners whom the Nazis ordered to strip their brethren of gold teeth and hair before cremation, she said. The Nazis wasted little.

Herzberger was at her physical peak when she entered the camp, due largely to her fencing training, but by April 1945 she was exhausted. At the Bergen-Belsen camp, she collapsed into a pile of corpses and felt she might die. A British soldier found her, barely alive, during the camp’s liberation. But as she recoverd, Herzberger and her mother learned that her father and uncle had died at Dachau.

Eventually, Herzberger met and married her husband, Eugene, now 94, who practiced neurosurgery in the U.S. after they met in medical school in post-war Romania. The Fountain Hills couple have two children, two grandchildren, and a great-granddaughter.

For more than 20 years, Herzberger suffered regular nightmares and depression before she began writing poetry and exploring her unconscious trauma through vivid dreams. That led to the penning of numerous poems, musical compositions and other art. In the 1990s, she began the challenging task of writing about her experiences in the concentration camps. In 2005, she published her biography, “Survival.”“My desire to write was so strong, nothing would prevent me from doing so,” said Herzberger, who also has a new book about the psychology of survival coming out next year.

‘A very rare opportunity’

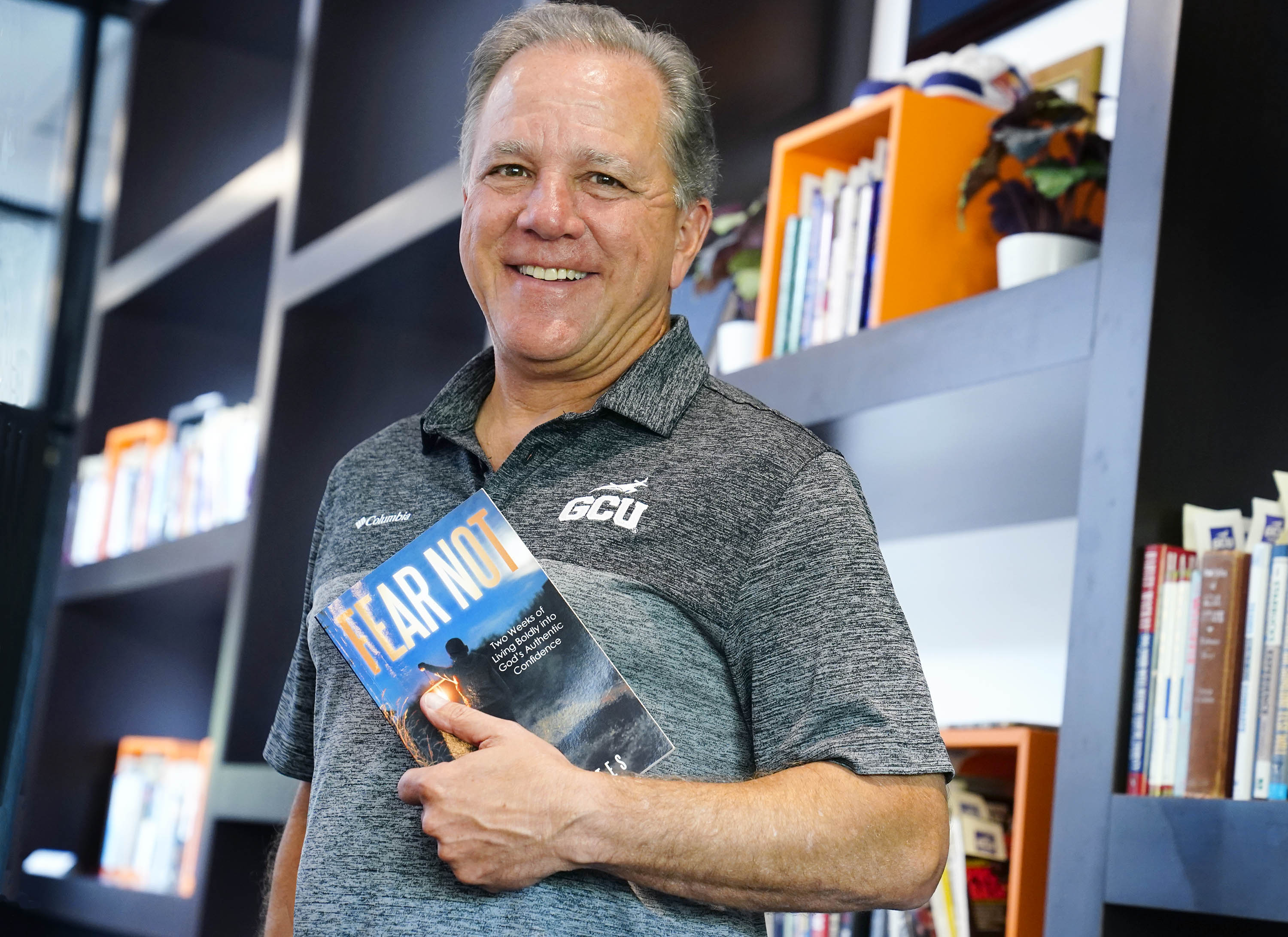

Dr. Sherman Elliott, dean of GCU’s College of Humanities and Social Sciences, has attended and coordinated Holocaust education events for nearly 20 years. But Wednesday’s event is unique, Elliott said.

Those organizing events about the Holocaust sometimes are unable to provide universities or schools with people who survived a Nazi death camp. Survivors are often not well enough physically to make the trip, or not able to speak effectively to a large audience. Elliott said the children of Holocaust survivors tend to speak for their parents.

As the total number of survivors dwindles each year, much like the roster of American servicemen who fought in World War II, the time students have to ask direct questions or hear the stories firsthand is limited.

“It’s a very rare opportunity, so they’re most likely not going to have it again in their lifetimes,” said Elliott, who lists Holocaust education as one of his top research interests.

Elliott was 15 when he met actor Robert Clary, who played Cpl. Louis LeBeau on “Hogan’s Heroes,” during a presentation of Holocaust survivors. Elliott recalled how one glimpse of the number tattooed on Clary’s forearm propelled him well beyond the details of his high school history books. Clary and his family were interred at death camps much like Herzberger’s and many others from across Europe.

“It was a real event, (Clary) was a real person who’d survived a horrific experience,” Elliott said about the moment when he realized the impact of the Holocaust.

“He had that permanent mark,” he said. “He couldn’t scrape it off. It would be part of him until he died.”

Those details are what make Holocaust education compelling, said Dr. Michael Trevillion, a program director and associate professor in GCU’s College of Education.

Trevillion recently formalized GCU’s partnership with the national Holocaust Memorial Museum, which will provide Holocaust evidence, texts, multimedia and expert speakers available to the University through the grant-funded Holocaust Institute for Teacher Educators program.

As a former history teacher, Trevillion said he experienced the challenge of using limited information to teach children about the grim realities of the Nazi genocide during World War II. GCU was selected by the national museum as a site to host historical resources, so that future teachers can understand how to convey the Holocaust to young people in Arizona and beyond.

It’s not an easy topic, Trevillion said, but it’s essential, given the systematic execution of innocents in the Middle East and elsewhere. History has the power to repeat itself unless everyone takes the time to understand the facts, he said.

“Actually having all the shoes they wore in a pile, seeing the evidence of it — it stabs you right in the heart,” Trevillion said. “I think exposing (GCU future teachers) to the realities and true evidence will give them the tools to carry on that mission.”

Reach Michael Ferraresi [email protected] or 602-639-7030.