By Mike Kilen

GCU News Bureau

Oskar Knoblauch was just 18 and stood bone still before the Nazi, pretending he couldn’t understand his language. He knew the conversation would determine whether he lived or died.

“I don’t have a job for that skinny Jew,” the Nazi said, and Knoblauch stood stone-faced, knowing it meant certain death.

“We all knew we would die, it was just a matter of when,” Knoblauch said.

Another Nazi officer entered the room, a man who 75 years later would become an example of virtue to Grand Canyon University students assembled before Knoblauch on Tuesday. A man who would be an example to a half-million students in the Valley, from grade school to college over the last 15 years, who hear Knoblauch’s testimony of Holocaust survival but also his inspiration.

“This Jew,” he said, “is going to work in the boiler room.”

“I was at a point where my hope had disappeared. When I was given a job, I looked at things in a different perspective,” he told the students. “My life was spared by people who stood up for me, who didn’t necessarily like me as a Jew but as a person.”

Knoblauch has a name for them. They weren’t bystanders. They were “upstanders.”

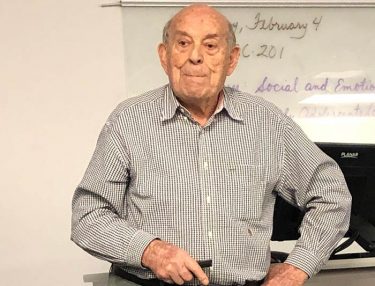

The roomful of GCU students in Assistant Professor Paul Danuser’s Social Justice for Educators class was locked in with attention. Here was a man of 94, among the dwindling numbers of survivors of the Nazi-occupied Poland ghettos, where entire families of Jews were herded into 10-by-10 rooms with no blankets to work hard labor with only 480 calories a day and snow for hydration.

“When you think of social justice, we have text books and we hear the news,” Danuser told the class before introducing Knoblauch. “But social justice is what he has lived through.”

Knoblauch showed a photograph of his family, in a happy time in Germany in 1932. He was 7. He loved school and sat in the front row. He loved playing in a sports club with his lifelong friend. One year later, he heard, “We’ve got to get rid of the Jews.”

Jews were “alien people,” he said. The Nazi propaganda had heated up, hammering away at the lies until many people believed it. His friend joined the Hitler youth, burning books. His teacher told him he couldn’t sit in front anymore. He was forced to wear a sleeve armband bearing the Star of David.

His family left Germany for Poland and by 1939 the Nazis had arrived there, too. He was bullied, treated like a “sub-human.” Two years later, they were forced into the Krakow ghetto.

He learned to smile. He learned to tell the people who spat hate at him: “You don’t know who I am, but I do. I am proud to be a Jew.” Then he would walk away.

“I always learned to smile but never give in and never be afraid,” he said. “A smile never lets you down.”

Today, he told GCU students, the culture wants to compare and divide people by money, education, skin color. “We are all created equal. You are you,” he said. “Why do you want to waste your time hating anyone?”

Why be a bystander, one who stands by and watches the hate of others? “They are useless.”

There were plenty. They watched as 30 Jews stood in line for one toilet. They watched as people were rounded up in the ghetto, never to return. A stone quarry was filled with tens of thousands of bodies as the Nazis shot Jews before gas chambers were built, he said.

When he was 16, Knoblauch met a man while being forced to empty garbage cans driven by a Polish farmer. He smiled.

The man began to look out for him and sneak bread for Knoblauch’s family.

“I had no money; he didn’t expect money,” he said. “Yet he was risking his life. He could read signs that if anyone was caught helping a Jew, that person and his family would all be executed. So why did he help me?”

The man told him that the ghetto would be evacuated and told him to “go to the dump and stay as long as you can and don’t come back.”

Many were taken to their deaths. Knoblauch survived.

His father wouldn’t survive the war before the 1945 liberation. But Knoblauch would go on to live a full life, marry and have three children, settle in the Phoenix area and affect many more in his later years with his book, “A Boy’s Story/A Man’s Memory: Surviving the Holocaust 1933-1945,” and his hundreds of presentations, which caught the attention of Shawna Martino, an Online Full Time Faculty member who brought him to GCU.

One saved life affecting so many.

“Imagine what an ‘upstander’ can do?” he said. “They create things, they don’t destroy.

“Can you change things? Yes, you can. Help me out here. Change the world to be a better place.”

Sam Hanson, a GCU junior, sat near the front of the room during the nearly two-hour talk and came up to shake Knoblauch’s hand afterward.

Regardless of your situation, he learned, there is always hope.

Regardless of the challenge, he said, one can befriend people who change your life.

Grand Canyon University senior writer Mike Kilen can be reached at [email protected] or at 602-639-6764.