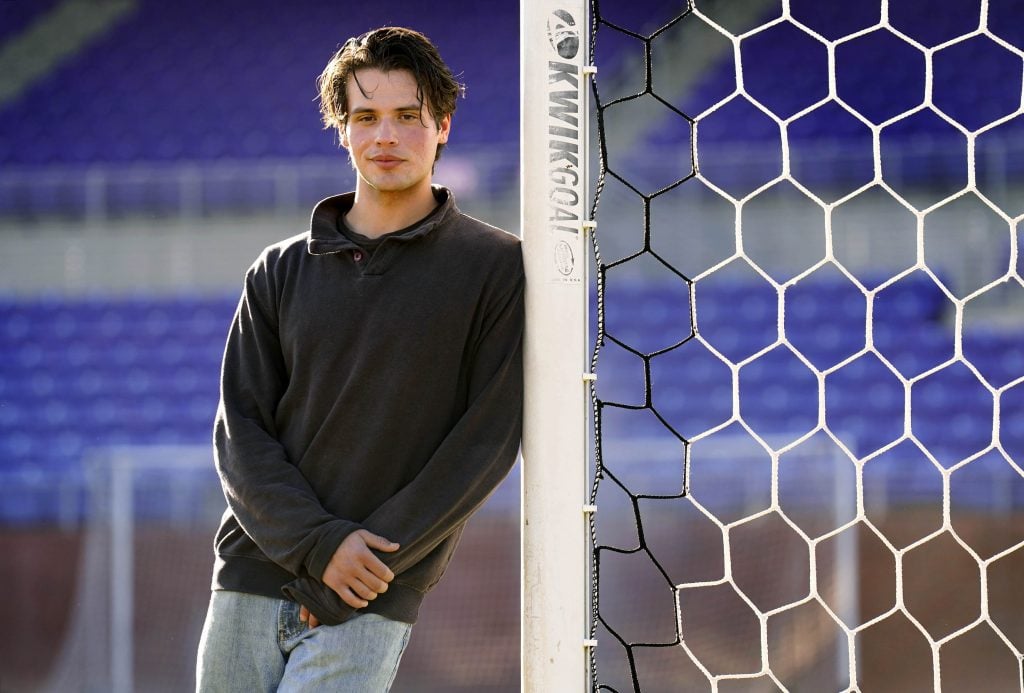

Photos by Ralph Freso

Rafael Guerrero’s mom says her son always carries a little notepad in his back pocket. He’s afraid he will lose his memories.

Bianca Burns Guerrero looks over at him, tall and gowned Thursday for college commencement outside Global Credit Union Arena, and chokes up a bit with the memory of his traumatic brain injury during a soccer game just across the Grand Canyon University campus four years ago.

But Guerrero is a writer, too, and that’s what they do, observe and write it down, just as he likely will about this late afternoon, when his mom said, “he had to learn to walk so he could walk.”

When asked how it all feels to him now, after relearning to walk, talk and then travel and study to earn a professional writing degree at GCU, he doesn’t offer any contrived, cheery answer. It’s not in him.

“I will say that I'm feeling loss pretty heavily right now. This school was my last and final tie to soccer – my first love, I guess,” he said, looking out at the revelers on the lawn outside the arena. “So graduating is bittersweet in a way, but it’s sweet when I get to reflect on how much I’ve grown.”

In a way, he said earlier, the injury doctors would say he shouldn’t have survived changed his perspective and brought him outside himself.

Since he was 3, growing up in Tucson, Arizona, he was stricken by that first love of soccer. It saved him in later years when his father was deported to Mexico, and with his single mom and two siblings, “He had to step into the role of the man of the house,” Bianca said.

The family hopped among friends’ sofas for six months, homeless, before she found a job and a two-bedroom apartment. Rafael was painfully shy and unwaveringly determined.

“He always packed his own stuff, washed his clothes, made sure his water bottle was filled. When I was working two jobs, he would run six miles in 105-degree weather to get to soccer,” she said.

Rafael said it was his way out. He rose to excellence, getting an offer to join a professional developmental league in Utah by age 15. The family left him there, driving back wondering how to make it back on “eight dollars and some change.”

A stint with FC Tucson soccer followed before he joined GCU’s team in fall 2021, and as a freshman goaltender, he was a wonder. But in the sixth game of the year, as the clock ticked off the final seconds against Seattle U, he faced a charging attacker to the net.

He dove out with his arms outstretched, deflecting the kick to save the game, but the player’s knee slammed into his forehead, opening a wide gash as Rafael crumbled to the turf. He was knocked out for 10 minutes and lay on the field for 23 minutes before an ambulance took him away. His mother in the stands thought he was dead.

The impact caused bleeding in his brain, which twisted and tore, and the diffuse axonal injury left him in intensive care for days and in the hospital for weeks. Months of therapy followed.

He couldn’t even write his own name.

“I never doubted that he wouldn't be OK,” Bianca said. “I just know him. He has greeted his recovery the same way that he has greeted everything in his life, especially soccer. He is tenacious.”

Rafael remembers now the first wobbly steps, the return of his speech, the hope. He really thought he might play soccer again. Doctors said it was too risky. So in the next year, he traveled to Europe, keeping that notepad filled with his thoughts, his memories. He studied at GCU online, battling depression and anxiety as a fallout from his injury, and was confused what to do with his life.

He had tried environmental science and psychology, but when he returned to campus in 2023 and met with professional writing assistant professor Kimbel Westerson, it became clear. Journalists had widely covered his injury and recovery, and he took inspiration from it.

“Why not discover other peoples’ stories?” he asked. “I mean, other people are as interesting as I am.”

He dove into the study, and Westerson said with his work ethic and “ability to dig deeper and take on more challenging subjects, such as immigration and social injustice, showed a level of engagement that’s rare.”

Under Westerson’s guidance, he found himself as a writer, and more.

“I feel like I had trouble connecting. Soccer was my community; it gave me friends and family. So after soccer, I had a really hard time and started isolating, had suicidal ideation. It was a very emotional time. But then this gave me something concrete, gave me motivation to get out there and ask questions. Wake myself up.

“There’s a world just as complex and important as I am – outside my head.”

Grateful for retaining his GCU scholarship, he could travel more in 2024, going to several Asian countries and writing. While Bianca said the intense planning and detail was training to trust in his memory and cognitive skills, Rafael saw it as a way to get outside himself.

“Living Outside the Self” was the name of his blog, as he detailed his encounters with strangers and his thoughts on the fact that his brain, like his forehead, would always have lasting scars. “So do I stay angry at the world?” he wrote.

Instead, he engaged. He got internships in Arizona doing research for the Arizona Sonora Border Projects for Inclusion, which provides help to low-income families and another to write newsletters for the Border Community Alliance toward its human rights initiatives.

He took a stint as a news reporter at an Idaho Falls, Idaho, TV station and filed daily stories. But he found the emphasis on hard, quick facts and a focus on his own dashing looks too shallow. He wants to write, and deeply, tackling an ongoing project that details the health effects of water pollution on a Tucson family.

Long-form journalism took him out of his comfort zone, he said. It was beyond the who and when. It was the why – why he had survived this has turned into why others can survive.

He doesn’t know yet where it will take him, likely to Latin America, with his notepad in his back pocket.

“My injury is chronic, which brings up a lot of fears of what my future looks like as far as my cognition and my intellectual abilities, so I have this obsession to learn new things. From my experience with soccer players from around the world, the best way to do that is through people.

“Coming off a blank slate, I will be curious. The dreams that I once had are gone, so I want to pursue something new, go out there and be curious and ask questions and learn.”

Grand Canyon University senior writer Mike Kilen can be reached at [email protected]

***

Related content:

GCU News: Five words shattered her dream, then set her on an unexpected path

GCU News: Commencement speaker talks the walk, from war-torn Syria to GCU stage