Editor's note: Story originally printed in the February issue of GCU Magazine, which can be read digitally here.

Story by Lana Sweeten-Shults

Photos by Ralph Freso

GCU News Bureau

Nathan Olsen was in the middle of his freshman physics Zoom class at Grand Canyon University in 2020 when his suitemate, Erik Yost, popped in and blurted, “Hey! You want to send something into space?”

Olsen shot back, “Yeah!”

“Then we got all the boring paperwork out of the way,” said Olsen, who, with Yost, volleyed ideas, mission statements and club names in what would become the formation of STELLAR, perhaps the most buzzed-about program on campus.

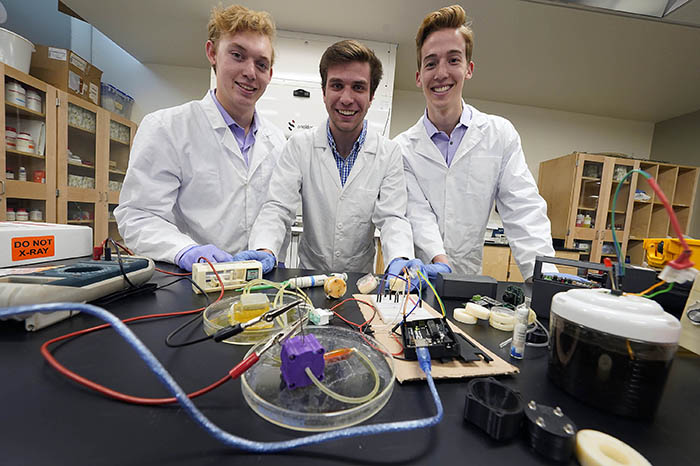

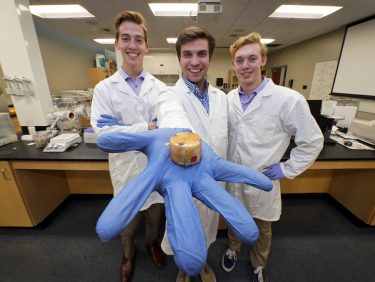

One part club, one part research group, the now 15-member team under the mentorship of GCU’s Dr. Jeff La Belle will be sending its microbial fuel cell to the U.S. National Lab on the International Space Station in April.

Not long after the paperwork was out of the way, the then freshmen invited business major Camden Marasco to campus coffee shop GCBC for their first pitch. As a high school senior, Yost took a Discover GCU campus visit with Marasco as his host.

Yost and Olsen asked, “Hey, you want to be part of this club?”

“I was like, ‘I’m way too busy to be part of a club. Like, there’s NO way,’” said Marasco, who at the time hustled from class to class and divided his time between the Finance and Economics Club and the Honors College.

Yost chirped back, “OK. Cool. So you’re NOT really interested. By the way, if you did it, we’d have to raise well over $50,000 to do it, and we’d have to do that by April at the latest.”

The way-too-busy Marasco was intrigued.

He didn’t know much about space.

He didn’t know much about engineering a microbial fuel cell.

He didn’t know much about fundraising.

But ...

“It was definitely one of those wild-card decisions that you have to make,” he said.

So began this all-out sprint to raise a seemingly insurmountable amount of money in just a few months so STELLAR could send its first project into space.

But much more than that, they wanted to come up with a project that would help their fellow man.

Every form of invention

The first big hurdle for STELLAR — it stands for Space Technology and Engineering for Launching Life Application Research — was to fund their research ambitions.

The group found out that as a new research team, it was not eligible for NASA’s Small Business Innovation Research grant.

“So we had to use every form of invention that we had to come up with to raise ... I think we just passed $74,000,” Marasco said.

About $30,000 of that would be set aside for the ticket to space and the reservation on the ISS. The rest goes into research.

The trio brought the idea to campus leaders. GCU President Brian Mueller, Vice President of Student Affairs/Dean of Students/University Pastor Dr. Tim Griffin and Director of Alumni Relations Noah Wolfe were invaluable resources.

They directed them to campus resources, such as the Research and Design Program grant, which funds undergraduate research at the University. Yost also was helped by a connection at Quest Institute, a NASA partner, while STELLAR landed grants from GCU and NASA sources, donations from individuals and from the University’s recent Day of Giving.

“It just sort of all added up — everything that we needed — but there were definitely times we thought, ‘We’re going to miss this deadline. We definitely don’t have the money,’” Marasco said. “But, thankfully, it all worked out.”

An electric idea

With a reservation on the ISS a go, the team has a little more room to breathe these days as it continues to develop its microbial fuel cell.

Yost, a sophomore studying biology, business management and Christian studies, first started sending experiments into space when he was part of his high school’s ISS team.

It was through that experience that he had the opportunity to work with NASA.

One of the experiments he sent to the ISS involved looking into the electrochemical characteristics of a microbial fuel cell in microgravity.

Scientists at NASA’s Ames Research Center in California’s Silicon Valley have been looking into microbial fuel cells for the past few years to see if they can use these microbes to perform essential functions on future space missions, such as generating electricity or treating wastewater.

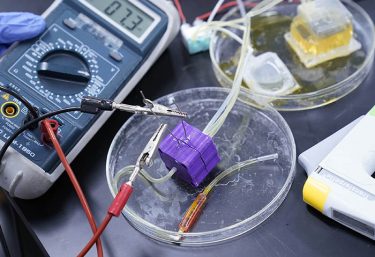

What STELLAR’s microbial fuel cell does is harness the power of bacteria to break down waste and turn the energy released during that process into electricity. As Yost puts it,

“Basically, bacteria eat waste and breathe electricity.”

As the bacteria break down waste, they release electrons that are then captured in a circuit.

“That circuit is where we can put capacitors to store energy for later,” said Olsen, a sophomore majoring in mechanical engineering.

What the team wants to observe is whether the microbes in its fuel cell work the same in space as they do on Earth.

Like the scientists at the Ames Research Center, when Yost originally designed the fuel cell, he wanted to see how it might help astronauts on future space missions.

But his vision has changed.

The team members want to see if their microbial fuel cell can help people, not just on space trips, but on their mission trips to developing nations.

“While I was working, I said, ‘Wow. This has a huge application. I can really change the world with this,’” said Yost. “This is where the three of our hearts are and where our passions are at.”

Yost chose to come to GCU because, ultimately, he wants to become a missionary and use science and research to help people.

“I wanted to have a Gospel mindset within it. That was really my heartbeat with the whole thing because I was not able to have that while working (with NASA),” Yost said.

Added Olsen, “Our mission statement is really humanitarian research, not just research just to do research and say we sent something into space. We’re designing, but what kind of data can we get from space that’s going to help us make something better as we take it on a mission trip?”

STELLAR is using an electricity-producing bacteria called shewanella to power its fuel cell. It is one of the most commonly found bacteria in the world, which for the team means it will be available in dirt or any kind of waste during missions to any part of the world.

While the team can store electrons in a capacitor for later use, it also can put them directly in a circuit to power light bulbs in a developing country.

“You could go on a mission trip so kids can read at night,” Olsen said.

And STELLAR is planning a mission trip after the semester ends: “To bring technology, teach and just share the Gospel,” Yost said.

To the moon and back

Since STELLAR formed at that GCU residence hall suite, the program has grown to include 15 members from all of the campus’ undergraduate colleges.

“We really try to get a diverse selection of team members. We have all different perspectives, different skills,” Yost said.

The club is unique in that Olsen, Yost and Marasco believe it is the only student-led undergraduate team in the nation working in microgravity. The group meets weekly with La Belle, its mentor, and texts and emails whenever it does need help.

“They are very much self-starters and motivated,” La Belle said. “I just try to stay out of their way.”

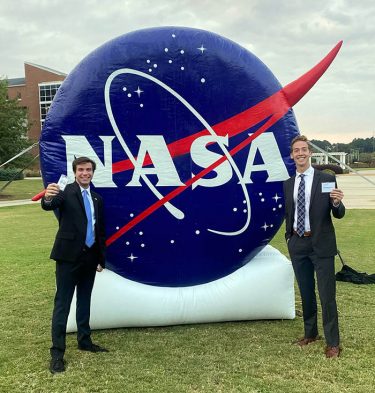

STELLAR competed this fall at the American Astronautical Society’s Wernher von Braun Memorial Symposium at the University of Alabama in Huntsville with its microbial fuel cell poster presentation.

The group followed that up by getting upgraded from a poster presentation to a keynote talk in the professional technical category at the American Society for Gravitational and Space Research’s annual convention in Baltimore.

If it performs well at one more competition, STELLAR hopes to receive an invitation to the International Astronautical Congress in Paris in the fall.

“Something we learned while we were in Alabama was … the time we’re working on all of this right now is really important because everything from this point forward has never been done before,” Marasco said.

It truly is a pivotal time in space travel, considering the space race between SpaceX and Blue Origin and the buzz surrounding NASA’s Artemis mission, which has plans to return astronauts to the moon in 2025.

NASA also announced its Watts on the Moon Challenge, a technology design competition that tasks U.S. innovators with imagining a next-generation infrastructure on the moon.

“As far as we know, we’re pretty much the only group that has a competitive, viable chance to actually produce electricity, because if there is electrochemically active bacteria out on the moon, we have a fuel cell that works in microgravity,” Marasco said.

What’s next for STELLAR, after its microbial fuel cell returns from the ISS, is a pizza party, of course.

And then the team will discuss what projects the group will pursue. Maybe it will continue with the microbial fuel cell, maybe it could be cancer research.

Whatever it is, it will embrace the program’s humanitarian mission.

Olsen said the group eventually wants to have four teams of 10 working on different humanitarian space projects.

Yost is already thinking beyond the moon.

“Camden had always joked around about the hashtag #tothemoon, and now there’s a real chance we may be sending our stuff to the moon,” Yost said. “Now we’re all like, dibs on Mars.”

GCU senior writer Lana Sweeten-Shults can be reached at [email protected] or at 602-639-7901.

***

Related content:

GCU Today: STELLAR makes final push as space launch nears

GCU Today: Another STELLAR performance by research group

GCU Magazine/GCU Today: CSET to launch new engineering programs next fall