EDITOR'S NOTE: This story was originally published in the August issue of GCU Magazine. Access the digital magazine here.

Photos by Ralph Freso

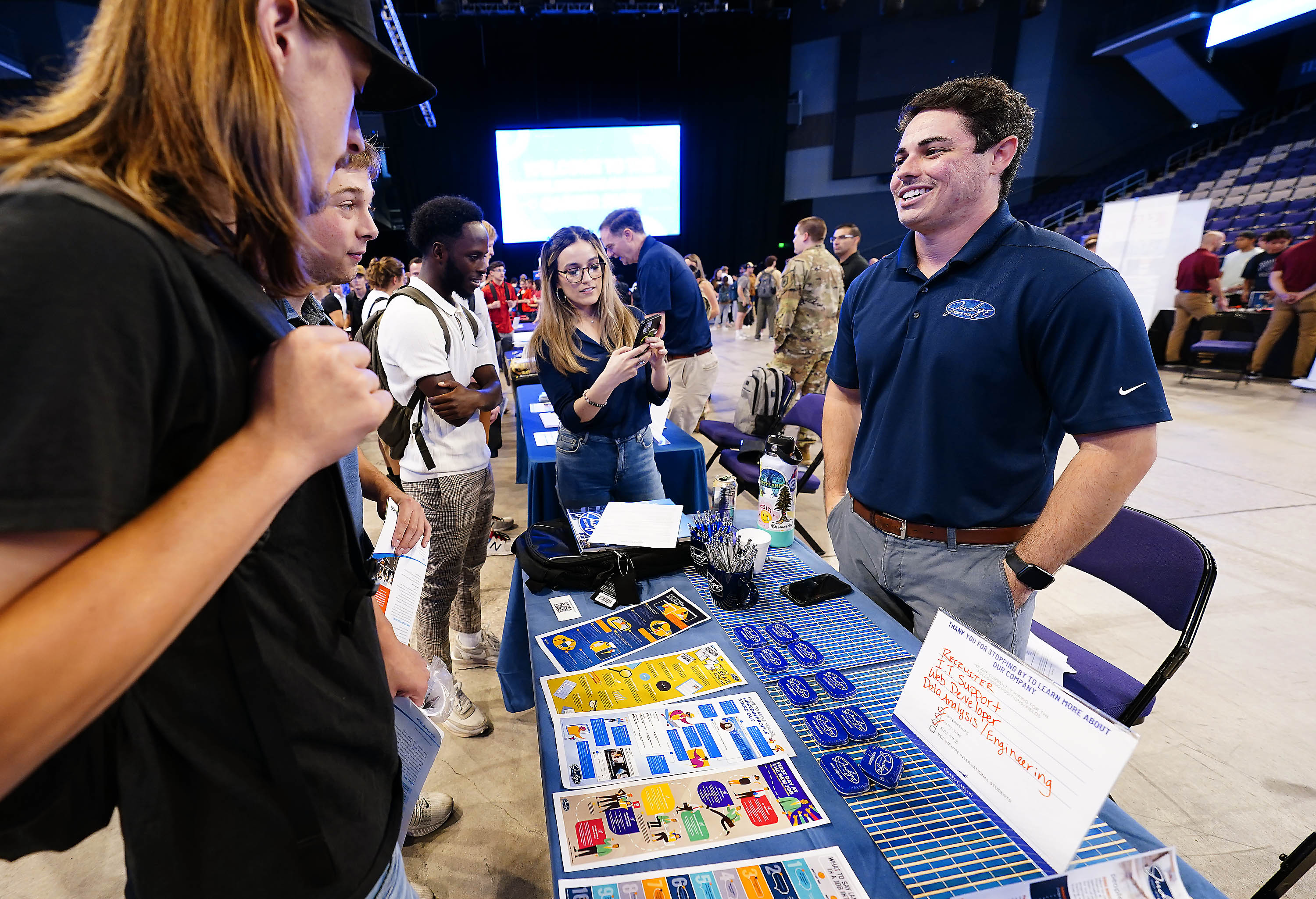

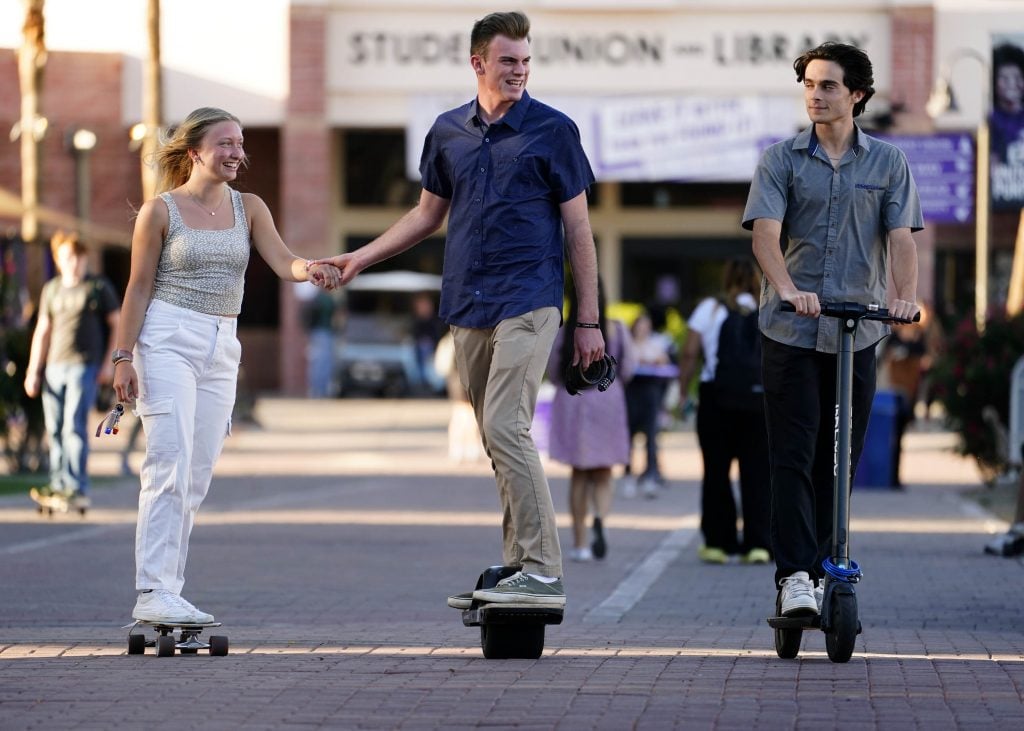

Students are like a river flowing through campus, the gentle drift of walkers aside a faster current of skateboard and scooter pilots flowing around corners, weaving through obstacles, their wheels sounding like water over rocks.

Few other college campuses feature this pronounced display of flow and motion, so much that skateboards and scooters have become a part of Grand Canyon University’s identity, a sunny, wind-in-the-hair freedom combined with business-like efficiency to get where you need to go.

On one morning in April before first classes, backpack-laden students rode with remarkable skills. Some anyway.

Student Trey Hall was just getting used to a small scooter, one foot kicking behind him to propel it through the courtyard outside the Colangelo College of Business. The borrowed scooter was not electric, like so many today, but to him that was a joy.

“After riding this, I’m looking to get one,” he said. “It’s great for the legs.”

That’s how the trend has grown, one student at a time.

On that day, in a two-hour timespan, there were nearly 850 wheeled contraptions, or what the experts call micromobility devices, parked outside classroom buildings. Nearly 70% were electric-powered scooters, another 25% both electric or nonelectric skateboards, in addition to a few electric e-bikes, bicycles or one-wheeled skateboards.

“One estimate is we now have 13,000-14,000 on campus, double the number of micromobility devices from two years ago,” said Brad Anderer, GCU director of Environmental, Health and Safety, whose office is leading renewed enforcement measures this fall.

Instead of outlawing them, like some colleges do, GCU has embraced their benefits to students. It’s part of its history, according to one man who can best wax poetic about its origins.

In 1998, Michael Shapiro carried his skateboard to GCU from his hometown of Prescott, Arizona, where his great-grandfather once attended the college that was born there 75 years ago. As far as he knew, only Shapiro and his roommate had skateboards on the then-small campus.

When Shapiro ventured back to GCU after 20 years away, he was blown away by the wheeled culture at GCU, which “rather than barring or banning it, they embraced it,” he said. GCU is the perfect size for it today, he added, big enough that it’s a way to get to class quicker yet small enough that a bicycle would be overkill.

“What’s lovely about skateboarding to classes, you get a little taste of freedom, the air flowing through you, feeling motion and movement,” he said. “Students are more alert, there is chemistry involved with the flow, and neurochemicals get your brain focused while trying to stay upright.”

If it sounds like he knows a lot about it, he does. He reunited with GCU to bring children from foster care to visit campus through Swappow PLUS Foundation, a Phoenix nonprofit that uses skateboarding to inspire goalsetting and confidence to realize individual potential.

“We have a lot of parallels between skateboarding and life. Where you look is where you go. Falling isn’t failure. And a lot of others,” he said.

Skateboarding helped spur on more than a nonprofit. At least two successful companies were launched by the culture. Levi Conlow conceived of the idea for Lectric Longboards as a student in 2015, which he then manufactured on campus, and went on to found electric bike company Lectric eBikes. Weston Smith also utilized the campus business incubator, Canyon Ventures, to create Lux Longboards. He transferrd the computer numerical control, or CNC, technology he used to power his longboards to launch Lux Precision Manufacturing, which makes parts for the medical field and other industries.

For students like Grace Yankey, it’s just a way of life. She’d long enjoyed riding her longboard, and when the nursing student came to GCU, it was perfect. “When it’s hot, it’s better than walking,” she said.

But it takes practice to get good on a longboard, she added.

One sees practice firsthand on shorter boards near the Canyon Activity Center. It’s where a skateboard park, which the students call “The Slab,” was created in 2019 as a way to capture the love of skateboarding that goes beyond a mode of transportation.

“We know that none of the other universities in Arizona have a skate park like this on their campus,” Director of Campus Recreation Matt Lamb said of the cement area that added obstacles such as rails and ramps and, last year, a new half-pipe.

Laeten vanDyck fell in love with it. “It’s like the best feeling ever when you land a trick and have been trying for months,” said the April 2024 graduate who was the president of the GCU Skate Club. “If you take the time to learn to ride a skateboard, you most likely are going to be aware of your surroundings.”

That group also elevated the reputation of GCU skateboarders and brought their love of it to the community, meeting at a local skate park in a disadvantaged area of the city to cook burgers and lead Bible study, developing a relationship with the neighborhood kids.

Others on campus simply see this wheeling about as a convenience. Student Ciara DeJongh said she grew tired of having sweaty clothes under her backpack after walking in the heat.

“It’s about convenience,” she said, hopping on her electric scooter. “It used to be a social thing. Now everyone has one, so it’s more like having a car.”

Maddix Drager said his electric scooter can go 15 miles per hour. “I ride it to get to class faster,” he said while unlocking it outside the Student Union. “Some people go way too fast. Definitely look over your shoulder. Some people should not ride.”

What started with the romance of the stereotypical free-spirited skateboarder, a sort of lone iconoclast, has evolved into mass culture that requires policing. That’s where student worker Emma Milton came in last spring as she wore a reflective vest on Lopes Way to monitor students and enforce a rule requiring students to dismount before going down the busy avenue of eateries.

“The vest does the job,” she said, “We can’t go tackle people — 75% follow the rules.”

A young man flying past on a scooter represented the 25% just seconds later as she hollered for him to dismount. “Cats are getting run over,” she said. “But it’s gotten better as the year has gone by.”

It’s created an interesting study of how skateboarders and scooter riders view each other, Milton said, each with their own stereotypes, which the psychology graduate studied as an example in class.

The university is increasing its efforts to maintain calm and ensure safety this fall, Anderer said. His office has compiled the location of accidents and created two more areas where riders must dismount — on Colter Circle and in front of the arena.

“Most of the causes are clumsiness, riding on a flat sidewalk and they just fall. But some have groceries in one hand and a phone in the other,” he said.

Enforcement of existing rules will increase. Students on wheels must have at least one free hand, no passengers and yield the right of way to pedestrians. Electric scooters must be approved by Underwriters Laboratories and can’t be charged in residence halls. The biggest rule is following the speed limit.

Some electric scooters, he said, can go up to 60 miles per hour, and 70% of accidents involve those devices. The speed limit is 15 miles per hour and will be enforced. Parking in correct areas also will be enforced, with a new lot and rails added this year, as well as posted QR codes to report near misses, already a success last spring, he said.

But a morning on campus is enough to see why it’s worth it. A young man pushed off — one, two, three times — and mounted his board, weaving like he was catching a wave, his head thrown back, a smile on his face.

Related content:

GCU News: Slow your roll: Student leaders on board for safety