By Michael Ferraresi

GCU News Bureau

Rather than jumping directly into homework after class, Michael Thang returns to his Camelback Hall dorm room to replay lectures from his digital recorder.

The 22-year-old freshman listens to his lessons a second time, at least. But even then, he may still struggle to understand concepts and cultural nuances unheard of in his native mountainside village in Burma.

Thang — whose Burmese name, Ceu Lian, translates to “shining light” — gently scolds himself under his breath that his English should be sharper, but those close to him might disagree. It’s been only two years since his family moved to the Serrano Village apartment complex just a couple of blocks east of Grand Canyon University, joining other families relocated through international refugee resettlement programs from Iraq, Bhutan and other war-ravaged nations.

For the past three years, GCU students and staff have forged a stronger relationship with Serrano Village residents by tutoring them in English, providing toys for children during the holidays and hosting residents during campus events. One group of students known as the Good Neighbor Club has befriended Serrano youths like Thang through mini-golf, bowling and other pursuits to take their minds off the anxiety of living like a foreigner. Those relationships already have proved to be lasting.

Thang is one of three Serrano students now studying at GCU. He is considering an accounting degree, although his undergraduate work might prepare him to study political science and eventually return to Burma to assist his own people. For him and the other Serrano students, the nearby Christian campus could mark the beginning of a new journey that could help ease the impact of years of suffering unfamiliar to most Americans.

“All my life, and this happening,

is how God had planned it for me,” Thang said. “I want to complete my education at least through college. I feel like God has led me here.”

Thang lives on campus and appears like any other college student, often sporting a flat-brimmed baseball cap turned backward, skinny jeans or DC sneakers.

Yet the story of a refugee student is far from ordinary.

Michael: ‘How God had planned it’

Before coming to the United States, the Thangs — who were raised Christian — lived in exile for six years after the military dictatorship in their native Burma drove many of their ethnic Chin brethren from the home villages. Soldiers burned their churches, replaced their crosses with Buddhist icons and terrorized residents in an ongoing conflict that dates to World War II.

His family’s flight from religious and political persecution forced Thang to miss high school as they grappled with life as refugees in Malaysia. When he arrived in Phoenix, he was 20 years old and needed to start as a high school freshman. He was told he was too old and had missed too much time.

But Thang earned his diploma in less than two years through the Blueprint Online Education program offered through his Phoenix Chin Christian Fellowship church and was provided a scholarship to attend GCU.

“We face a new culture, new food, a new social living standard,” Thang said about assimilation to the U.S. “It’s very hard for us.”

Rather than giving in, though, Thang has emerged as a leader among Chin youth and remains involved with as much as he can at GCU, including playing his brand-new Les Paul guitar at faith services.

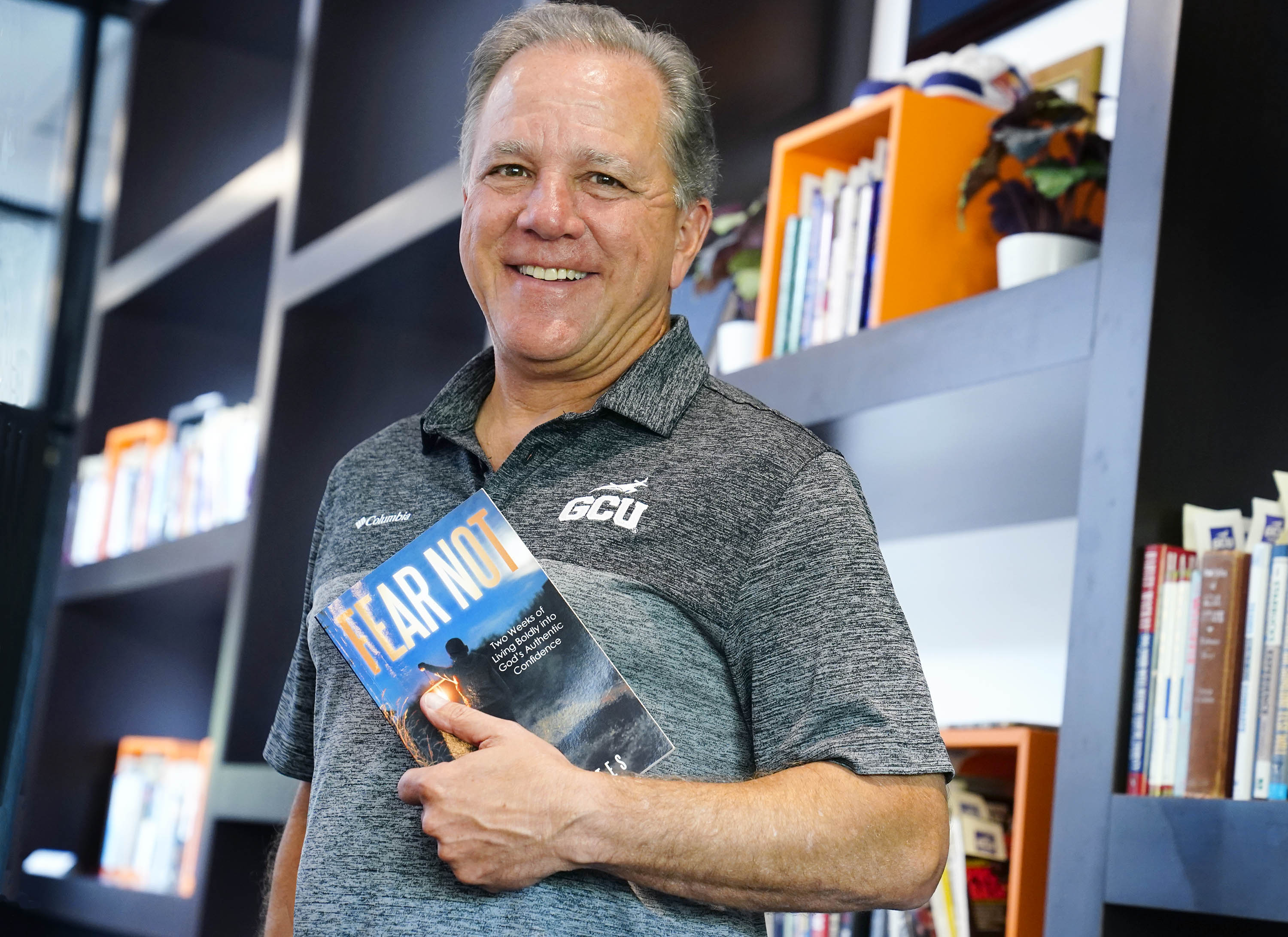

Jonathan Sharpe, a College of Theology instructor at GCU, organized the Good Neighbor Club and has helped with efforts among students, staff and Serrano residents.

Sharpe said the low-income apartment complex, whose owners work with international refugee groups to help residents get acclimated to American life, should be the beginning of a new way of life for residents — rather than a symbol of where they’ve been pigeonholed to live permanently.

Americans tend to send money overseas to help with refugee resettlement efforts, Sharpe said, while few recognize the same opportunity located right down the road at a place where more than 580 people from 15 countries are trying to regain stability in their lives.

“There’s a huge piece there that most American kids don’t understand about what it means to break through in this country,” said Sharpe, who was inspired to help with refugees after learning about the Lost Boys of Sudan.

“They’ve experienced what it’s like on the other side of the American dream,” Sharpe said. “They desperately need people to show them how to save money, how not to get into credit debt, how to write a resume…. I just have so much respect and admiration for students like Michael who are changing the future for their families and often are carrying an entire community on their backs.”

Bawi: Changing a family’s future

The headlines about ethnic protests and military force bring back bad memories. So Bawi Tial tends to ignore the news from back home.

She focuses on her job washing dishes at the Sheraton in downtown Phoenix, attending church, helping her family and doing her schoolwork. But she lives with an uncle who recites the reports, following the details about the ethnic Chin minority in Burma — also known as Myanmar — as if he’s providing a play-by-play of human rights abuses.

“We don’t ask him,” said Tial, who manages a beaming smile even with noticeable pain in her voice. “He just tells us. But I never watch the news by myself.”

At an age when most American girls are dealing with the stresses of entering high school, Tial was separated from her parents when they fled Burma. Her mother faced arrest for her work in anti-government politics. So her parents left for the refugee shelters of Malaysia until Tial could take the same journey with a grandmother one year later.

Although her parents only made it to the sixth grade, Tial is taking classes on psychology, physiology and nutrition with the hope of earning a degree in nursing. Her dream is to be a surgeon, though she was inspired to work in nursing after spending so much time aiding the same grandmother who helped rescue her from Burma before she passed away.

“They’re proud of me,” said Tial, 21, a sophomore who left her parents’ apartment at Serrano recently to make space for her two brothers and two sisters.

“They support me going to school,” she said. “They just say, ‘Keep studying.’”

Edith: Defying the path

Bodies were stacked in the streets. Children were being conscribed as soldiers.

The violence grew so bad so fast that Edith Kamara’s great-grandmother helped her “escape” from their native Sierra Leone when she was 3 years old.

| How you can help |

| For more information about GCU’s efforts to help residents of Serrano Village Apartments in Phoenix, or about how to help yourself, contact the complex at 602-242-5910. Students interested in assisting refugees should contact GCU refugee outreach ministry leader Faith Albright at 602-903-9311. |

They fled to neighboring Liberia. Both countries have undergone brutal civil wars, but the escalating fighting in their homeland fragmented Kamara’s

family so quickly that she ended up estranged from her mother for nearly six years. She remembers meeting her mother when she was 9.

Kamara, a 19-year-old freshman nursing student, moved to Illinois with her family as Sierra Leone coped with the aftermath of a decades-long conflict

that left tens of thousands dead. She landed in an American grade school where she felt mocked and ridiculed by her classmates because she was an African refugee.

The family moved to Phoenix and landed at Serrano, where she lives with her mother, four brothers and a younger sister. The morning battles for bathroom time, she said, can be epic. So her walk down Camelback Road to her

classes can be refreshing.

“It allows me to walk, rather than be lazy,” said Kamara, who speaks English confidently but with a distinct African accent.

After excelling in soccer and track at Alhambra High School, she decided to study nursing after seeing the starvation and amputees from the war in her homeland.

In Sierra Leone, less than 25 percent of women are considered literate, according to the CIA World Fact Book. Kamara said her relatives remind her how she’s beating the odds at GCU.

Her mother and great-grandmother never had an opportunity to attend college. As she grew up in the United States, her great-grandmother reminded her that she could be whatever she wanted, more than a housewife or laborer.

“She really changed my life,” Kamara said. “She told me to defy that path and change the rules.”

Contact Michael Ferraresi at 639.7030 or [email protected].