Story by Lana Sweeten-Shults

Photos by Katie Severns

GCU News Bureau

Dr. Stephen Meyer was speaking in Dallas recently on stage with a fellow presenter and noticed a camerawoman crying.

She had been a biology major in college, but more than one professor hammered home the contradiction between science and the belief in God.

“She had found herself increasingly discouraged, and she hadn’t quite entirely given up her faith, but she gave up her scientific aspirations and left college with an unresolved sense of tension -- a kind of cognitive dissonance,” Meyer said.

That camerawoman later wrote to him.

“Throughout my college career,” she said, “professors would constantly lecture that, based on the evidence they had provided, there should be no way anybody in class could believe in God. … I was desperate to find a commonality between my beliefs and my scientific education.”

She could not find one.

“It’s not hard to understand why young people in the sciences often feel this tension between scientific knowledge and religious belief,” said Meyer, an advocate of intelligent design and the director of the Center for Science and Culture at the nonprofit Discovery Institute in Seattle.

That story, one Meyer shared Friday during his opening talk at Grand Canyon University’s first Conference on Faith and Science in Antelope Gym, shed light on the reason for the two-day conference: to show that religion can coexist with science.

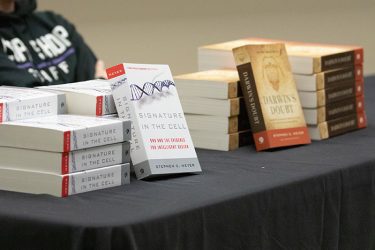

The event, brought to campus with the help of GCU's Dr. Mike Mobley, brought together speakers who shared their thoughts on intelligent design, theistic evolution, social ethics and Christian philosophy of science. It also featured a poster presentation of various research projects by GCU’s students.

“Why are we doing this?” asked GCU President Brian Mueller of hosting a conference that tackles such seemingly oppositional ideas as faith and science.

He had the answer. He told the audience about majoring in theology and history at Concordia University in Nebraska 44 years ago. He wanted to be a teacher in Christian schools.

“I remember at graduation how those of us who were going into the teaching and preaching ministry got calls into sacred vocations and how blessed we felt to have that experience,” Mueller said.

It wasn’t the same for his friends who majored in biology and chemistry and other sciences, who “just got a job.”

“I thought, coming out of a Lutheran tradition, how wrong that is, because it was Martin Luther who said that all vocations are equally honoring in God’s eyes,” Mueller said.

He then expressed how it is the goal at GCU for every student to believe they are being called into a sacred vocation, whether they’re a biologist, chemist, engineer or a preacher.

“We want to flood the marketplace with Christian young people who are smart, ambitious and want to make a difference … by taking their passion for engineering and combining it with their Christian conviction. Most importantly, if they will take that into the darkest places in the world, in the places that need the most help … it will make a difference, it will transform the world.”

The conference, sponsored by the American Scientific Affiliation with support from Desert Hills Presbyterian Church, attracted more than 800 attendees, said College of Science, Engineering and Technology biology professor Dr. Daisy Savarirajan. (You can watch Friday's session here and Saturday's talks here).

“The crowd was very diverse -- students, faculty, people from churches, Christian schools and educators from other colleges, like CHSS (the College of Humanities and Social Sciences) and Theology. It’s very, very broad,” she said.

That diverse crowd began those two days of talks with Meyer’s “Return of the God Hypothesis,” which explored the tension between scientific knowledge and religious belief but also declared that there is a shift in thought among scientists, who are going from an atheistic worldview to a theistic one.

He spoke in particular about the New Atheists in the early 2000s, such as Richard Dawkins, author of“The God Delusion.” It was Dawkins who said that before Charles Darwin, there was a powerful reason to believe in God. But after Darwin, the idea of intelligent design in nature -- the purposeful arrangement of things in nature that lead us to believe in an intelligent designer (God) -- is not real but merely an illusion. There’s an unguided process called natural selection acting on random mutations, which explains the appearance of design. Since Darwin, Dawkins said, the suggestion is that intelligent design does not exist and, therefore, there is no public evidence for the reality of God.

Meyer said Dawkins’ worldview is a materialistic worldview, in which matter and motion are all that exists. Materialists reject the idea of immaterial or spiritual entities. Add to that the philosophical idea that God did not create man; man created the idea of God.

“This was an increasingly dominant way of looking at the world coming out of the 19th century and into the 20th, and it was allegedly based on science,” Meyer said, “ … But support for that materialistic point of view is evaporating.”

Three big discoveries, he continued, are pointing to the realities of an intelligent designer:

- The first big discovery is the thought that the universe had a beginning (the Big Bang Theory), and if it had a beginning, someone started it -- God. Meyer pointed to how Edwin Hubble showed Albert Einstein that the universe must have had a beginning. Through his large dome telescope, Hubble determined that the universe’s galaxies were moving away from each other -- that the universe was expanding -- and if you go back in time, those galaxies would then get closer and closer to each other and, eventually, to a point of origin. Meyer also pointed to modern cosmologists and the cosmological argument: Everything that begins to exist must have a cause. The universe began to exist. The universe must have a cause. “Modern cosmology is now confirming the first words of the Bible, “In the beginning …” Meyer said.

- The second discovery: The universe has been fine-tuned for human life to exist. Meyer referenced physicist Fred Hoyle, who wrote: “A commonsense interpretation of the evidence suggests a superintellect has monkeyed with physics and chemistry, as well as biology, to make life possible.”

- Finally, a digital code is embedded in humans’ DNA, but where did that information come from? Who wrote the code? A master coder? God?

Besides Meyer, conference attendees heard from Dr. Jeff Hardin, board chair of BioLogos and chair of the Department of Integrative Biology at the University of Wisconsin, who spoke about “Why Believing in God Makes Sense in an Age of Science”; Dr. Tom Buchanan of the University of Delaware, who on Saturday presented “I Muse on What Thy Hands Have Wrought: Reclaiming Science for Christ”; and the Acton Institute’s Dan Churchwell, who spoke on Saturday about “Technology, Freedom and the Future of Work.”

Savarirajan emphasized how GCU is committed to civil and enlightening discourse as a means for developing critically thinking students. Through conferences like this one, the hope is that the University will "generate science-literate Christians who will not shrink away from science but see it as a means to solve society’s pressing problems for the glory of God."

Dr. Jason Hiles, Dean of GCU’s College of Theology, noted how important it was for the University to host this particular conference.

“GCU is emerging as a major educator in the STEM areas, and we are doing so as a private, Christian university.”

The conference encapsulates how committed GCU is to scholarship in the sciences while embracing the values of a Christian worldview. Many people think, he said, that a university can only focus on one or the other, which is why many of the sciences are shaped by secular worldviews.

“We are not only developing programs that are vital to the needs of industry. We are also offering a curriculum that intentionally shapes character and emphasizes human flourishing as the proper end of scientific and theological advancement,” he said.

Savarirajan added that she hopes students who attended the conference will gain a clear understanding of different and sometimes conflicting worldviews and that they will have "compelling reasons to stand strong in their Christian faith as they learn to see the world through God’s eyes and live their lives based on God’s word."

In the end, Hiles said, the conference shows how no one has to choose between faith and science, like that camerawoman in Meyer's talk felt she had to do: “Faith is a starting point for knowledge, not the end of the search to understand all that God has done,” Hiles said. “One who believes wholeheartedly in God can also conduct amazing research projects in ways that enable us to better understand who He is and how He created.”

GCU senior writer Lana Sweeten-Shults can be reached at [email protected] or at 602-639-7901.

***

Related content: