Story by Karen Fernau

Photos by Travis Neely

GCU News Bureau

Playing dead kept Joseph Gamunde alive as Islamic militants gunned down classmates at their desks.

Wild fruit and sporadic rainfall kept him from starving or dying of thirst as he fled the bloodshed in his homeland of Sudan.

After he watched his father get executed, faith kept his heart beating and his feet moving toward safety.

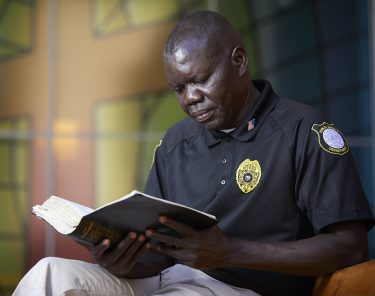

“My Bible, my faith. They are the only weapons I had, and they kept me alive,” says Gamunde, now a public safety officer for Grand Canyon University.

Today, he still reads the same Bible he brought to Phoenix in December 2000 from the Kakuma refugee camp in Kenya. While working the evening shift at GCU, he keeps it stashed in his car and its words in his heart.

“It reminds me of where I came from,” says Gamunde, one of the Lost Boys of Sudan, the name given to the displaced South Sudanese youths who fled their villages to escape a war that began in 1983 and raged for more than 20 years.

Gamunde began working at GCU two years ago, yet few on campus know the harrowing life he left behind on a faraway continent. Only the remnants of his lilting, native Moro tongue hint at a foreign past.

The only time he talks about fleeing death in Sudan and eight years in a Kenyan refugee camp is when he believes his torment helps others shed theirs.

“I ask God to share with me the best so I can share the same with others,” he says. “I share both my pain and my joy. I tell them that whatever they go through, no matter how bad it seems, their troubles won’t be permanent. The best is yet to come. Always.”

Gamunde talks of his African past with the exactness of a historian.

The Second Sudanese Civil war stretched from 1983 to 2005 between the Islamic Sudanese government and the Sudan People’s Liberation Army. It lasted for 22 years and is one of the longest civil wars on record.

Yet, when he switches from the facts to memories, he speaks with the heartbreak of a man whose childhood was shattered by war.

Decades have done little to mute the horror of watching his father killed, learning of his mother’s death in an air strike, witnessing mass executions, dodging soldiers, facing starvation and the simmering hatred between religions and tribes.

Gamunde’s horror story begins as a 13-year-old attending school in a southern Sudanese town miles from his native village. His father, a minister with five children, had come to visit.

“The ruling Islamics decided anyone from a different place was a spy, an insurgent,” he says. “They put a hood over his face that was filled with a poisonous powder. I watched him die, and the insurgents told me that’s how they killed.”

Gamunde and his classmates were then ordered to attend an Islamic brainwashing school. After two short weeks, the teacher learned that rebels were on their way to rescue the students. He opened fire.

“My best friend was shot and his blood was all over me. ... The blood let me play dead. My friends died,” he explains.

After the schoolhouse massacre, he and other teenage refugees began a two-year trek through jungles and deserts, zig-zagging their way past government troops to the safety of a neighboring country. They avoided villages, towns and walked only under the protection of darkness. They had hope but no maps, no planned route.

“I had no idea where I was going, but I knew that if I got there, I would start a new life,” he says.

To survive, he risked eating plants not knowing if they were deadly. “I believed what God says, that even if you drink a poison in his name, you will survive,” he said.

Gamunde often survived days without water or food. Slowly, his newfound family of refugees shrank as many died from the hardship.

Only a last-ditch miracle spared them after they had decided to stop and die together rather than one by one along a tenuous path.

Without water, they knew death was inevitable. Together they sat on the desert floor and prayed. Fifteen minutes later, dark clouds swept over them, dropping life-saving rain.

“The rain told us that God intended for us to survive,” he says.

His ragtag group finally arrived at a refugee camp in Kenya, where he spent eight years working from 5 a.m. to 11 p.m. every day. He made do with a cup of beans a week.

As a teacher, he passed on what he learned in school to the camp’s children. As a minister, he employed what he learned from Sunday school, his father and the Bible to help others embrace Christianity.

As peacemaker, he diffused intermittent violence between warring tribes.

“I did everything I could to make sure we lived in harmony and peace,” he said. “My tribe was called cowards because we didn’t believe in killing. For others, killing was easy.”

After years of red tape, he was granted, at age 24, permission to emigrate to the United States.

He flew to his new country with 89 other Boys of Sudan, moving into his first apartment near the GCU campus.

At first, he worked on the manufacturing floor of Valley semi-conductor companies, but after several layoffs he accepted a job with a private security firm, where he worked for nearly a decade.

A former co-worker encouraged him to apply to GCU two years ago, and Gamunde remains grateful.

“I finally feel like I am in the right place,” he says. “I don’t have to hide my faith. I can bring it to work.”

Case in point: the cross on his uniform’s patch and the privilege to occasionally pray with a student.

GCU also shares many of the academic values of his African family and tribe.

“We believed in education, ministry and health care. What was important to us is right here on campus,” says Gamunde, a father of an 11-year-old son.

The stories of South Sudanese refugee children have been told in books, movies and documentaries.

Gamunde, however, prefers sharing face to face how he keeps past demons at bay or channels war-scarred memories into acts of kindness.

“All that I’ve seen that’s so terrible has shaped me to see life in a positive way,” he said. “I choose love over violence. I look for good in the worst of times.”

Contact Karen Fernau at (602) 639-8344 or [email protected].