Photos by Ralph Freso

A latex-gloved RyLee Williams carefully side-stepped down the sloping gravel to the edge of a small canal along Little Canyon Trail that runs through Grand Canyon University’s campus. She leaned over carefully and used a sterilized bottle to scoop up the water.

That was scary, she said.

One wouldn’t want to fall into the milky brown canal. The day before, GCU professor Dr. Berenise Charlton’s legs slipped into the shallow water, only later to find out when the water monitoring test results came back that it was high in E. coli, a type of bacteria from fecal matter. It could have been pooping birds or even an upstream homeless encampment’s waste working its way through Phoenix’s elaborate canal system that diverts water from the Colorado River, explained Charlton.

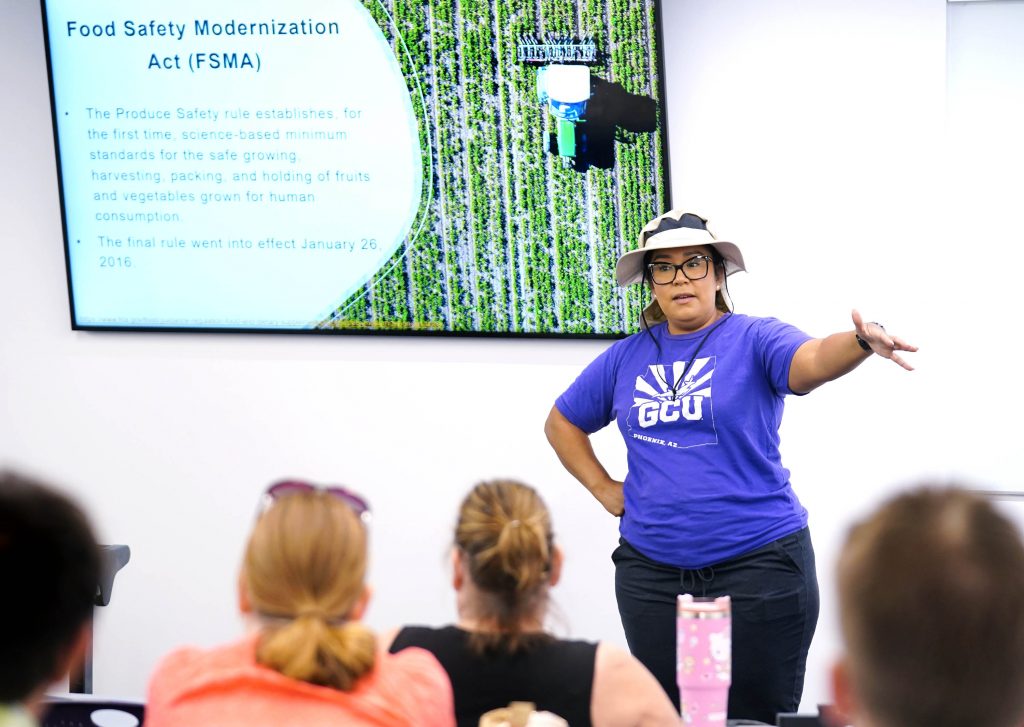

She was leading a group of teachers and students Tuesday attending the first two-day Urban Farming Education Conference, a collaboration with GCU’s College of Natural Sciences, K12 Educational Development and the Phoenix nonprofit Urban Farming Education.

“Because water is used to grow crops, we have to measure its quality,” Charlton said, describing recently finalized government rules through the Food Safety Modernization Act.

Like many of the 150 teachers or students who attended, Williams wants to start a garden at her school, Chandler Traditional Academy-Freedom Campus, and the conference brought university experts, research and resources to do it.

“It will provide a hands-on learning experience and share the impact that nature has,” Williams said of a school garden. “I’ve learned there are so many resources available and so many in the gardening community who are willing to help support you.”

Water quality is just one factor in growing gardens. The conference explored dozens of topics, from composting and the science behind growing seeds to working with nonprofits and grant writing.

Another third-grade teacher at the canal, Silvia Vega of Ethos Academy in Glendale, also wants to start a school garden.

“They can find another vision of the world through a garden and education,” she said. “If you combine those, you also teach them sustainability, how to grow a garden in their own home and save money.”

If it sounds like a trend, it is. Urban Farming Education’s goal was to help start one school or community garden a month. But in the last six months, it’s been double that.

Dr. Joe Roselle, chief operating officer at Urban Farming Education, started the largest community garden in Arizona, Agave Farms, which produces more than 1 million pounds of produce to donate, but it’s also facilitating the growth of urban agriculture throughout the Valley. He said he’s helping develop curriculum in schools and bringing organizations together to launch the gardens and keep the projects sustainable.

“We try to move schools from landscaping to a foodscape,” he said. “What we preach is a lot of this stuff is free.”

First they need to develop a purpose, and often growing food for the entire school is out of reach unless they have a sizable acreage. “What we do is advocate for instruction, so they can tie into their lessons and make it meaningful that way.”

Bringing in community partners is key, and it becomes a win-win. “Schools want it because they want hands-on learning, and the businesses want it because they want to support STEM education,” he said.

That’s where GCU came in. He says the university “walks the walk” and helped design this first-ever conference with its staff and facilities, centered out of Sunset Auditorium.

Dr. Cori Araza, K12 Educational Development senior project director, said the conference gives exposure to the College of Natural Sciences, including environmental science. But organizers also brought in experts from the University of Arizona Extension Community, entomologist Dr. Shaku Nair, and Peter Rillero, an associate professor of Science Education at ASU West College of Education. They joined Dr. Adrienne Crawford, a GCU instructor of biology, ecology and environmental science, in a panel discussion in Sunset on Tuesday.

Teachers and a class from Phoenix charter high school Maricopa Institute of Technology learned how universities are willing to help them with their gardens, even with new explorations by GCU faculty in the use of AI and drones in agriculture.

But what most impressed MIT student Aiden Muñoz was the GCU Garden.

“My idea was there were things you couldn’t grow, especially in the summer heat. Then we saw the strawberries and other things growing and it was amazing,” said Muñoz, who raised his hand to share with the group. “We thought it was impossible and thought they would die. So that was an experience we could learn from.”

GCU graduate student Ashlee Romine, who gave tours of the Outdoor Recreation Campus Garden, told the group that the garden has gone beyond a place to grow food for students who can buy a plot for $30.

Amid a sea of concrete and buildings and turf, she said, students have started going to the garden before or after class for a quiet time to reflect. “It’s kind of an oasis.”

Romine is studying for a master’s in nutrition, “so I am passionate about the food side of growing,” she said afterward. “I feel like this is a big goal. They might know how to grow, but to actually use it can be food security for students.”

They typically start newcomers with something fast-growing, carrots or radishes, and once they get that success, it takes off. Gardens are becoming more popular, she added, “maybe because food is expensive. I feel like a garden is growing money.”

Nearly 95% of the garden space was spoken for in the last academic year, as well as becoming a feel-good space for events, more than doubling participants to 1,200 during events held there, she said.

Food fresh from the ground brings people together, as Urban Farming Education program director Kim Rillero described. While it’s important that her organization helps impoverished people in Africa with their projects, she remembers best a moment at their garden outside a domestic violence shelter in Phoenix. A mother had not emerged from the shelter in five days, recovering from her wounds and trauma, but after her young son came out to pick a carrot, she brought all four children out to pull one and happily chomp on it.

“She sat there crying," Rillero said. "It’s healing.”

The garden also carried an empowering message. You can do it. You can grow things, all on your own.

Grand Canyon University senior writer Mike Kilen can be reached at [email protected]

***

Related content:

GCU News: Where the wild horses hang out – and other natural sciences projects

GCU News: GCU, MESA have designs on helping K12 students engineer STEM careers