8 • GCU TODAY

Like many elementary school teachers, Pérez is

required to bounce between math and vocabulary

lessons, following carefully crafted schedules to keep the

class on track. His strategy stems from what he learned

during his Rodel assignment. At one point, he shouted,

“CLASS, CLASS!” and a cacophony of well-trained

student voices replied, “YES, YES!” The brief din of

antsy conversation was quieted.

“I love how you followed the expectation, put everything away and

that it was done quietly,” Pérez said in an even tone that washed over his

Phoenix classroom.

So much of Pérez’s routine is patterned after his Rodel Exemplary

Teacher mentor, Raquel Mendoza, whose second-grade classroom at

Glenn F. Burton Elementary in Glendale was his final checkpoint to

becoming a professional teacher. Like Mendoza and other mentors who

have dedicated their lives to public school children, Pérez believes the

future of public schools in his native state is as bright as a student’s face

when — after all the patient, repetitive coaching — the proverbial light

bulb is flicked on.

After coming to GCU to earn a master’s degree in elementary

education, Pérez quickly emerged as a leader among his peers and

accelerated his career through the 16-week Rodel placement. The

program is intended to immerse future teachers in settings designed to

overcome challenges facing underperforming schools.

Back at the interactive learning board, known as “Number Corner,”

Pérez guided the class through math, money, time-telling and basic

geometry, using displays with coins in plastic holders, clocks with

adjustable hands and charts to help the students understand material on

which they will be tested.

“When I was a kid, I was thrown into the classroom,

sink or swim,” said Pérez, whose working-class parents

spoke Spanish in their home. He picked up English in

school and watched his mother struggle to understand

his teachers during after-school conferences.

“Teachers have more tools at their fingertips now

in the classroom,” Pérez said. “To me, it’s rewarding,

especially with the changes going on in education.

When I was in high school, they were barely phasing out typewriters

and introducing computers. That’s how I learned keyboarding. There

were no smart boards.”

Some of Pérez’s students still read at the kindergarten level. Others

have improved their reading skills more quickly. When he joined the

Cartwright School District and accepted the job at Sunset, five miles

west of GCU, Pérez knew he’d have to juggle a wide range of needs in

the class. Special ed teachers and reading and math specialists come in

and out most of the day, diverting students to other rooms for extra help

on speech or reading when schedules allow.

Solutions for a teacher shortage

Dr. Marjaneh Gilpatrick, GCU’s executive director of educational

outreach, said Pérez — a graduate student at the time — approached

her in 2009 to suggest that GCU partner with Rodel, since the College

of Education’s conceptual framework and mission and that of the

foundation aligned so well. With support from the dean and GCU’s

executives, she established the partnership.

“It’s expected of them as student teachers that, when they become

part of the Rodel program, they’re committing to a full, semesterlong

job interview,” said Gilpatrick, who is responsible for recruiting,

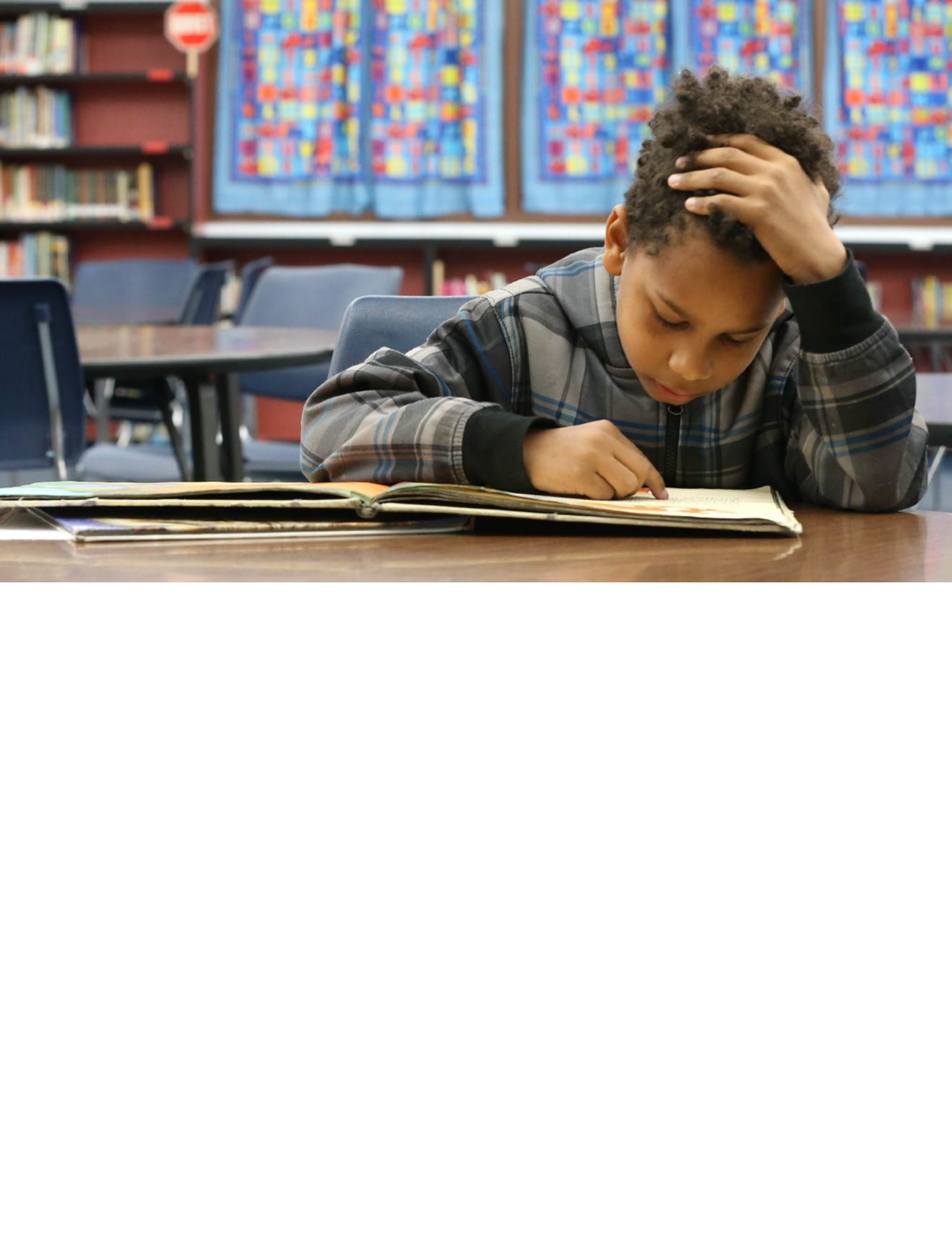

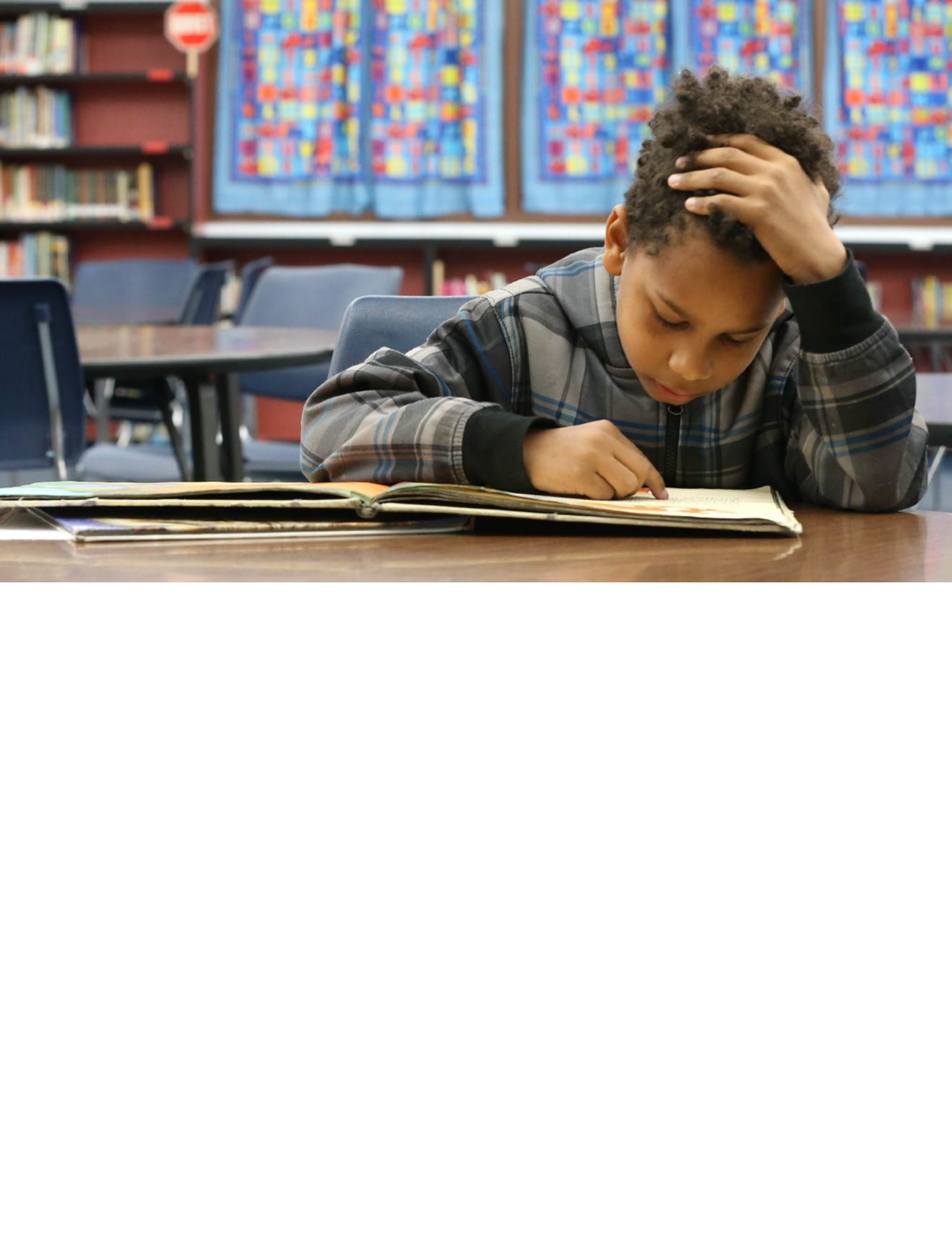

Sunset Elementary second

grader KyleWard, 8, works

through a book in the school

library. In many Arizona

classrooms, reading is a

challenge for both students to

learn and teachers to instruct.