fighting, but the distance hasn’t made coping any

easier. Some of his friends have been killed while he

has been at GCU, and he knows of another who was

abducted and has been missing for months.

Americans, he said, don’t understand the worry

that weighs on Ukrainians’ minds every day.

“It’s hard for people here to understand what

we’re going through because what they see on the

news isn’t what it’s really like. Being there and

seeing it in person, it’s much worse,” said Saiko, a

sports management major who goes by “Stas.”

“I don’t really even know what’s happening there.

I’m not home, I’m here, 6,000 miles away.”

Egyptians know the feeling

When Glazunov, Saiko and the other Ukrainians

need advice, they don’t have to look far.

Mazen and Youssef Elkamash, twin brothers

from Alexandria, Egypt, joined the GCU swim team

the same year as the Ukrainians and know what

it feels like to live through war. Bloody protests

that eventually forced President Hosni Mubarak to

resign erupted across Egypt in February 2011. More

than 860 people died in the monthlong revolution.

The twins, 19, remember tanks in the street

outside their home and looters robbing buildings

during the night. The government shut down

Internet and cable lines to prevent further uprisings.

“You could hear people shooting outside when

you slept,” said Mazen, who like his brother is a

sophomore business major.

Youssef said, “You couldn’t make a call, you

couldn’t watch TV, you couldn’t do anything, just sit like you are in a

cave. We weren’t really scared, but it was tough.”

The Elkamash brothers rarely left their house during the revolution.

They swamwhen they could

and occasionally joined

protests to stave off boredom.

They visited their older

brother, a swimmer at the

University of South Carolina,

in December 2012 and

decided they wanted to attend

college in America.

They found GCU online

and contacted coach Steve

Schaffer to join the swim

team. Leaving Egypt was

difficult — they dodged bullets and passed tanks on their way to the airport

and almost didn’t make it out.

The situation in Egypt has since calmed. The twins talk with their

mother often and don’t worry about her safety. They offer to talk to the

Ukrainians about their experiences when they need support.

“It’s different for Youssef and me than with the guys from Ukraine,”

Mazen said. “We were there with our family and friends. There were

still tanks and stuff when we left, but it was normal.”

“We know what it’s like and are here to talk when they need it,”

Youssef said.

Team’s success helps

Schaffer said he can tell by the Ukrainians’ body language when news at

home is bad. But they never complain or take practices off, he said.

“I think in one way or another all swimmers use swimming as an

escape from what’s going on in their lives,” said Schaffer, who swam at

UCLA and has been GCU’s coach for seven years. “They’re some of our

best swimmers. The reason we wanted to bring those types of guys in is

because they’re fast, and they’ve helped us this year.”

Glazunov agrees that the team’s success — and preparing for the recent

Western Athletic Conference championships — provided some relief. He

and Saiko are simply happy their families are alive. For now, they try to

focus on swimming and school and block out everything else.

Glazunov and Saiko have urged their parents to leave Ukraine but

know there is nothing they can do. They haven’t been home since moving

to Phoenix and don’t know when or if they can return.

They don’t worry. Maybe it’s better that way.

“I didn’t bring anything to remind me of home except clothes and my

(swim) suit,” Saiko said. “I don’t worry about it. After what’s happened

there, I just cannot go back.”

GCU TODAY • 1 5

I don’t really even

know what’s

happening there.

I’m not home,

I’m here, 6,000

miles away.

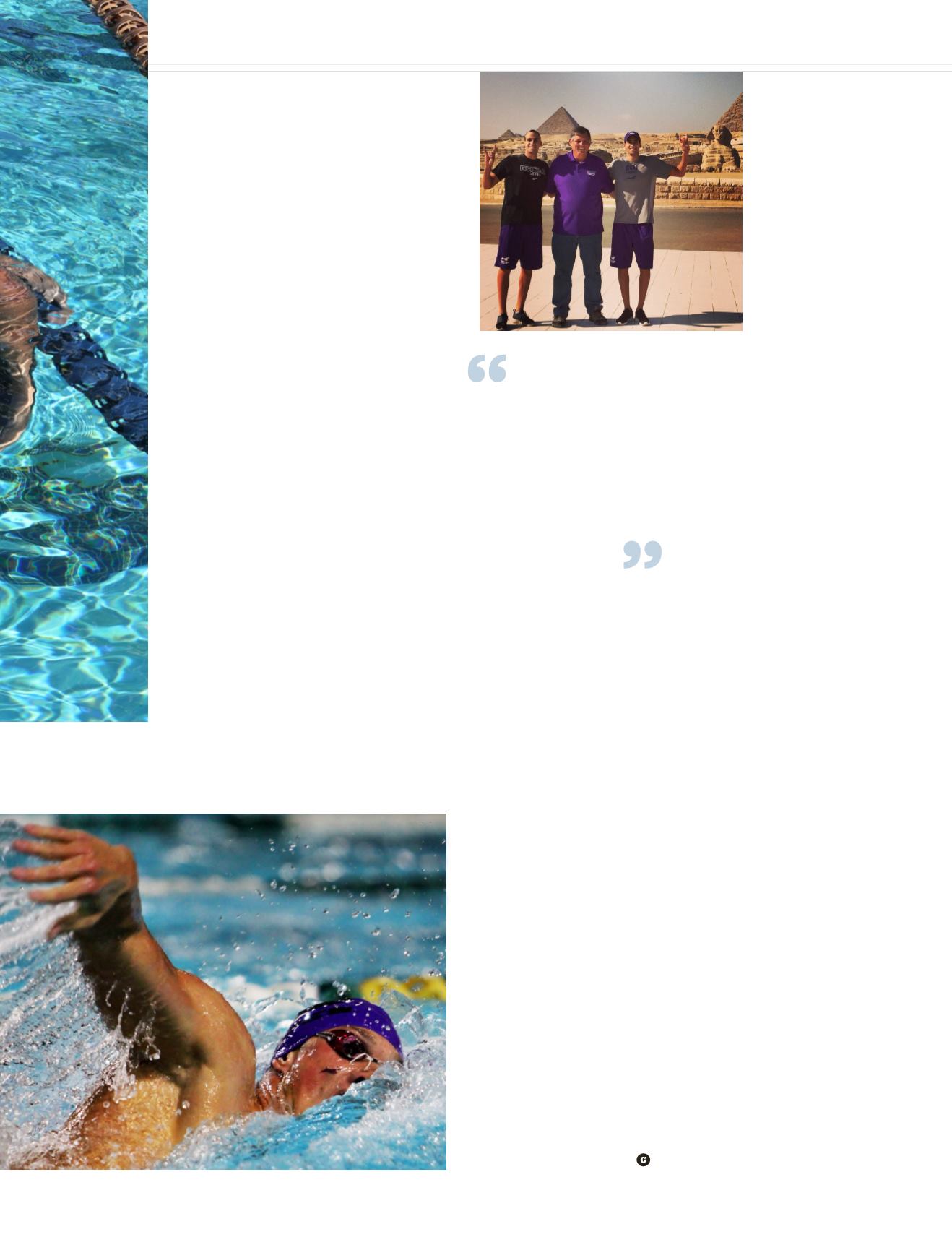

Mazen (left) and Youssef

Elkamash show their GCU

pride with swim coach

Steve Schaffer at the

Giza Necropolis outside

Cairo. Schaffer traveled

to the twins’ homeland to

watch them swim for the

Egyptian national team.

photo courtesy

of mazen

elkamash

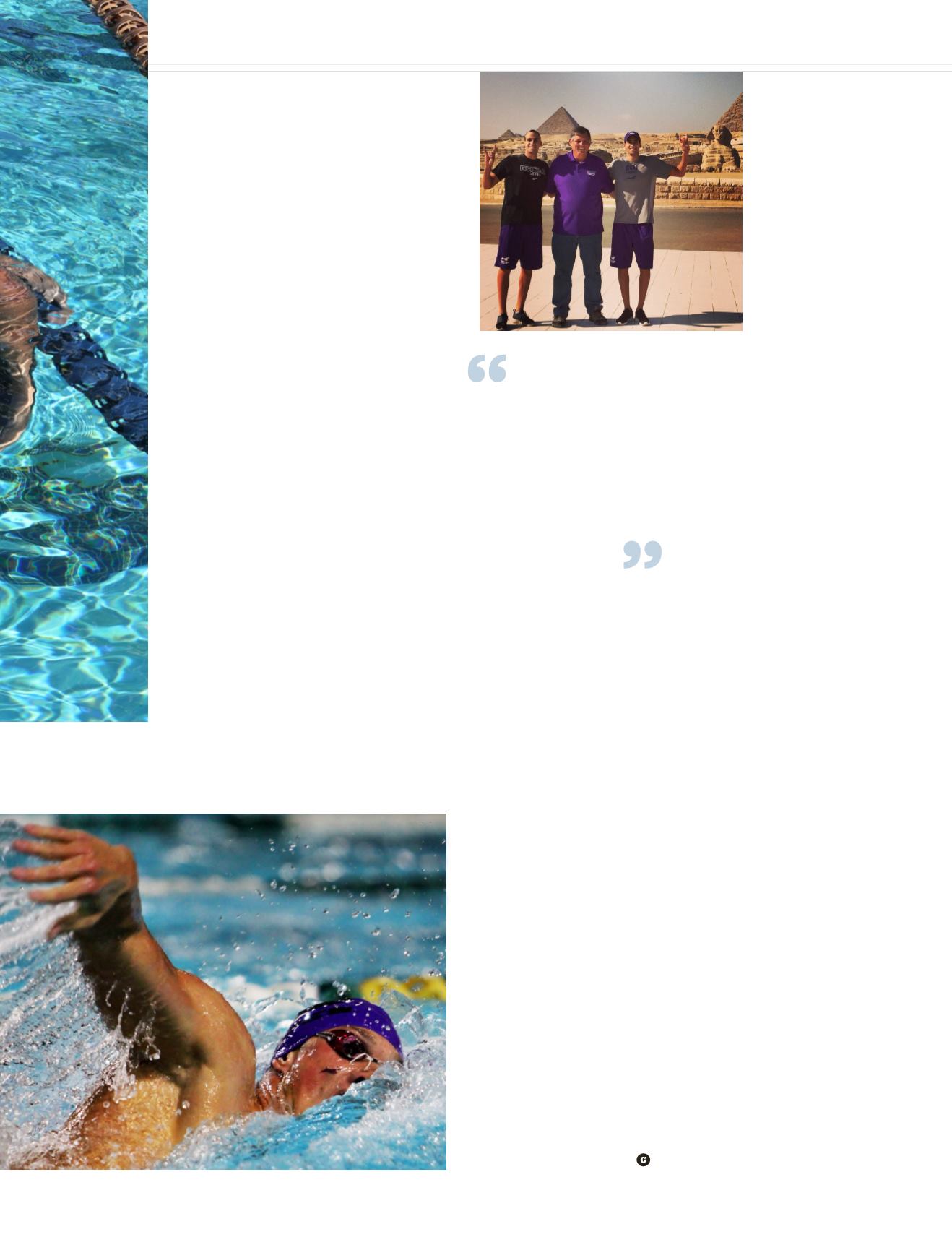

Swimming is a helpful

distraction for Glazunov when

news from home gets tough.

photo by deb

schaffer