Story by Lana Sweeten-Shults

Photos by Ralph Freso

GCU News Bureau

STELLAR didn’t exist a year ago.

It boggles sophomore Erik Yost’s mind that just 11 months after the group officially formed at Grand Canyon University, it is on the verge of sending its first project into space.

In just a few days, the team’s microbial fuel cell — a battery that harnesses the power of bacteria to convert waste into energy — will head to the Quest Institute, where it will be sterilized and prepared for its April 15 launch to the U.S. National Lab on the International Space Station.

“This is just super exciting,” Yost, a biology and business student and president and founder of STELLAR, said of the impending space launch and its implications. “…We’re setting the bar for all other universities and colleges that want to follow what we’re doing. … As far as I know, we’re the only undergraduate research team sending legitimate research to space.”

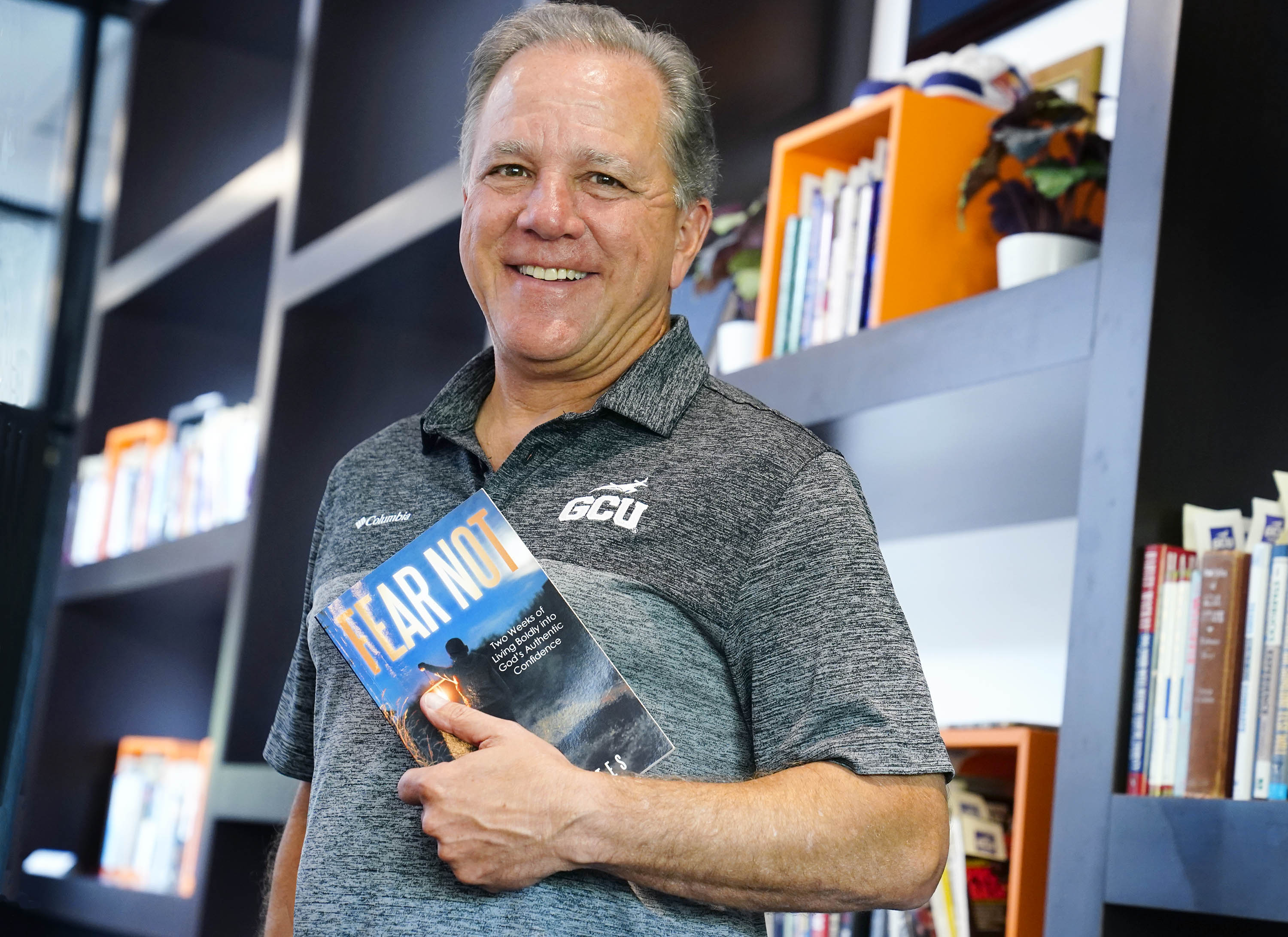

And they’re doing it with a thumbs-up from GCU President Brian Mueller, who on Monday visited with team members during the final stages of assembly as they made sure the fuel cell meets NASA protocol. He also donned a HAZMAT suit and signed the container housing the battery. (View slideshow here.)

In a way, Mueller will be heading to space, too. Well, at least his signature will be, along with the signatures of Dr. Randy Gibb, Dean of the Colangelo College of Business, and Dr. Mark Wooden, Dean of the College of Science, Engineering and Technology. They will be signing the battery container on Friday.

It has been an exciting time for STELLAR (Space Technology and Engineering for Launching Life Application Research), which operates under the mentorship of biomedical engineering professor Dr. Jeff La Belle. It was created as a platform for students to design, test, build and launch projects to the International Space Station.

Why send projects into space? The idea is that living organisms perform better in microgravity, where there is no shear stress, so the team expects that the bacteria in its fuel cell will produce more electricity in space. The team then can try to isolate why the fuel cell does better up there and replicate the genetic sequence on Earth to get it to perform at the same rate as it did in space.

Not that the group is sending projects into space just because it’s cool.

It's doing it with a humanitarian mindset.

The fuel cell, for example, not only might be used to produce energy for astronauts on space trips but to produce electricity for villagers in a developing nation.

“That’s why this is an exciting thing, because God did not create this world as a zero-sum proposition,” Mueller said of the project. “We’ve got plenty in this world that God has given to us so 7 billion people can prosper, yet we can’t figure out how to do it.

“But that’s the purpose,” he said of finding a way so that every human can flourish. “That’s what we should be doing in college, right? We should be doing the kind of work you’re doing. Figure out how to turn this.”

The 15-member team — a multidisciplinary group from eight of the University’s colleges — had to raise a seemingly insurmountable amount of money in just a few months to make its space-launch visions happen. The ticket to space alone cost $30,000. Somehow, STELLAR raised about $74,000 to fund the space trip and the group’s research.

Besides the funding challenges, challenges in the lab pushed the team, too.

Over the past two weeks, students worked late, often until 2 a.m., to troubleshoot leaks. They had to design, test and build an apparatus that would hold liquids without leaking into a zero-gravity environment.

“This was one of the mechanical engineering team’s biggest hurdles, as containing potassium ferrocyanide was not an easy task,” Yost said.

Team members designed bags they hoped would be able to withstand pressure changes and still could fit into their module. The bags continued leaking during testing, so the team had to regroup.

“I ran through about a dozen variations to fix the leaks,” said Spencer Hahn, one of STELLAR’s mechanical engineers.

Another team member suggested using acetone smoothing to prevent leaks. It worked.

Besides shoring up those leaks, the team was able to buy about $1,800 of bacteria, which allowed for only three tests, STELLAR Vice President and co-founder Nathan Olsen, a sophomore mechanical engineering major, said of the electricity-producing shewanella bacteria. The microorganisms release electrons as they break down waste – energy the team captures in a circuit and stores in capacitors for later use.

When the team ran its initial ground tests with the bacteria, it also ran into a lot of issues, which resulted in killing each of the experiments. Those were failures the team also had to overcome.

“The leaks were the last big problem that we faced,” said team member Madelyn Hendrikse, a biology/pre-med major. “It’s kind of crazy, though, because it really shows the teamwork. If one person’s portion (of the project) breaks, it affects everyone else’s part. And if someone’s part goes well, it also positively impacts other people’s portion. It’s a good life lesson of how teamwork is all-encompassing.”

The team is planning a launch party as well as a trip to Florida to watch the big event at Cape Canaveral. GCU’s microbial fuel cell will be headed to space from Launch Complex 39, “which is the same one that the Space Shuttle launched on for years … so it’s a super historical launch pad,” said Olsen, beaming.

STELLAR will be able to keep up with its fuel cell during its time at the International Space Station by receiving data via photo files.

“There’s a light inside that says whether it’s going good or it’s failed,” senior biomedical engineering major Clay Damkoehler said. “That’s the scary light; we don’t talk about the scary light.”

The microbial fuel cell will return from space about the middle of May, when the team will take the data it receives and begin work on a research paper it hopes to publish.

STELLAR Director of Business Operations Mackenzie Larson, a business management major, considers it awesome to be part of a team doing cutting-edge research. But more than that, she said, “It’s pretty cool to be a part of a team that’s motivated by a good purpose.”

Biomedical engineering major Aimee Milota said what she has treasured the most during her time with the team is this: “We are really researching the unknown. Everyone came in not knowing anything. Learning everything was the hardest, and also working together, trying to put all our brains together.”

Coming to the end of this journey is “kind of sad,” Milota said. “But it’s insane that we’re sending something to space – that’s crazy.”

Now all that’s left to do, Yost said, is make the trip on Saturday, not to space, but to the GCU Mail Center, with a project signed by University leaders that one day could impact humanity: “I’ll say, please send this to NASA. FRAGILE! HANDLE WITH CARE.”

GCU senior writer Lana Sweeten-Shults can be reached at [email protected] or at 602-630-7901.

***

Related content:

GCU Today: High school students research possibilities at GCU

GCU Today: Another STELLAR performance by research group

GCU Magazine: Houston: We have a passion (see page 18-21)