By Lana Sweeten-Shults

GCU News Bureau

Sara Bachofer wants to engineer prosthetics.

So when Grand Canyon University Biology and Environmental Science Professor Rachel Pikstein instead recruited her to design a nesting habitat for the once-endangered cactus ferruginous pygmy owl, the idea was a bit outside of Bachofer’s wheelhouse.

“She said her project needed engineering students, and she picked me. I said, ‘OK. I guess I’m doing this now,’” Bachofer recalled with a laugh.

The spring graduate of GCU’s Biomedical Engineering program became part of a Research and Design Program team that delivered a re-engineered nest box this spring to Wild at Heart raptor rescue in Cave Creek. It is the latest evolution of the box since its first design by GCU students two years ago.

The hope is to create a space for captive owls that will result in a higher hatch rate than current nest boxes and, ultimately, improve the owls' chances in the wild.

The cactus ferruginous pygmy owl is the second smallest owl in North America. It weighs fewer than 3 ounces and stands 7 inches tall when fully grown.

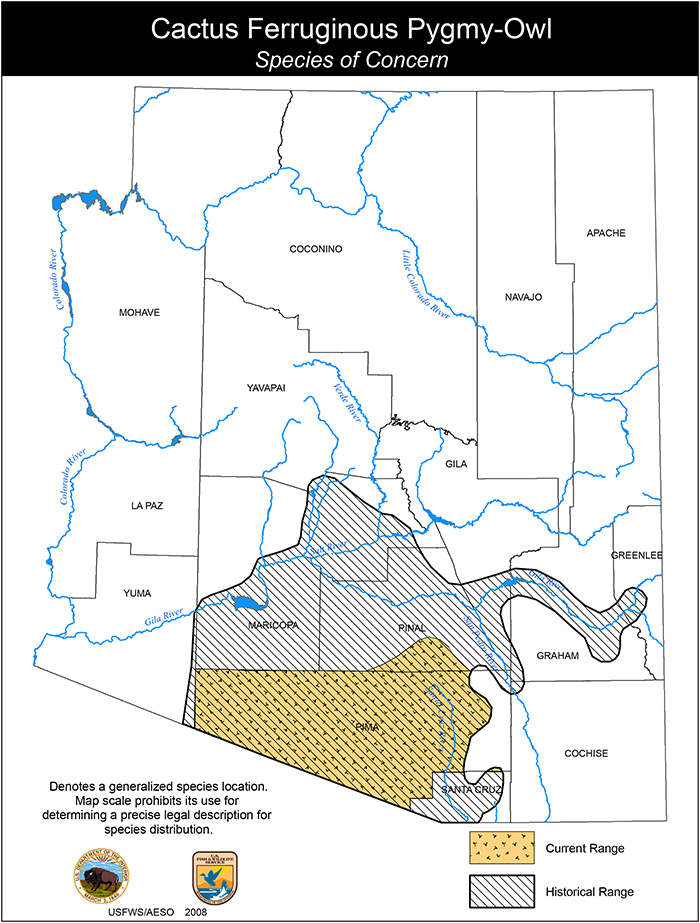

Native to the desert scrublands of Arizona, southern Texas and northern Mexico, they once lived as far north as Phoenix. But their range and population have dwindled since the 1970s. That decline has been attributed in part to habitat loss, including in Arizona, where the population growth is among the fastest in the nation.

By the 1990s, only about two dozen of the owls could be found in the central Valley, prompting the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service to place them on the Endangered Species List in 1997. It was where they remained until 2006, when they lost their protected status after a lawsuit was filed by the National Association of Home Builders. They are now considered a Species of Greatest Conservation Need in Arizona.

Fewer than 100 of this subspecies is thought to exist in the state today, according to the Phoenix Zoo’s Arizona Center for Nature Conservation.

Through a Fish and Wildlife permit, Wild at Heart captured the last of the owls in the central Valley to breed them, which the facility has been doing since 2007. It is the only non-Association of Zoos & Aquariums-accredited institution in Arizona with permission to breed a protected raptor species.

The organization has since began collaborating with the Phoenix Zoo, which received two birds from Wild at Heart in January 2018 and four more breeding pairs a few months later.

Both groups continue to work with U.S. Fish and Wildlife and the Arizona Game and Fish Department to breed the owls in captivity. They have had some success -- just last month, the zoo hatched nine owlets.

Not that the program hasn’t been without its challenges.

What’s unique about this subspecies – and what makes breeding them so challenging – is that they breed in abandoned cavities carved out by woodpeckers in saguaro cactuses.

Conservationists, such as GCU's team, are working hard to replicate that environment.

An earlier RDP team began designing the first nest box prototype two years ago as part of the Desert Owl Population Improvement project.

Early boxes did not produce the kind of results conservationists want to see. Eggs rolled inside the enclosures, humidity spritzers caused molding, and poor insulation and circulation affected hatch success rates, which reach barely 50% for owls in captivity compared to 90% in the wild, Pikstein said.

“The original nest boxes were a very plain, square wooden box,” Pikstein said. “They had trouble with various aspects of it not being similar to a saguaro in the way it insulates and how it functions.”

Wild at Heart wanted GCU to re-design a box using student engineers. So Pikstein partnered with College of Science, Engineering and Technology Biomedical Engineering Professor Dr. Kyle Jones, recruited Bachofer and added environmental science/prelaw junior Ted Orr.

They built on the work of previous GCU students and the research done by the zoo, which included temperature readings in the nest cavities of saguaros that once housed pygmy owls.

“We did a new approach where we incorporated temperature readings and humidity readings,” said Orr, who acknowledged how the saguaro cactus protects the owls' eggs from temperature extremes.

Since the team did not have permission to conduct thermodynamic tests on saguaros -- the cactus, unique to the Sonoran Desert, is protected by law in Arizona -- they performed tests instead on the anatomically similar golden barrel cactus.

“We spent a lot of time doing research on the cactus and what the ambient temperature was inside of it, what the humidity was inside of it,” Orr said. “We actually dissected a cactus and did a thermal test. We wanted to see how heat traveled through and how much time it took.”

They used a steam iron to apply constant heat to the cactus and recorded temperature change rates. From there, they were able to determine the cactus’ "R value."

“The insulation that goes in your house has an R value. We took the findings and found the best insulation that matched the cactus turned out to be an R13, which is a pretty standard home insulation," Orr said.

Bachofer and Orr, who presented a poster of their work at the spring CSET Research Symposium, created their nest box out of a 5-gallon plastic bucket, which resembles the interior diameter of a saguaro boot (the bark-like shell of the cactus). They insulated the bucket with R13 fiberglass and added a layer of 2-inch plywood strips so the owl could have something to grip onto while climbing in and out of the box.

The design also includes replaceable EVA foam for hygienic reasons, as well as a temperature probe, heat lamp and fan so the owl’s caregiver can maintain a set temperature in the box.

"What is unique about our nest box is it is the only one that uses real engineering technology and insight and addressed all the problems presented to us by the Phoenix Zoo and Wild at Heart," said Pikstein.

Bachofer said regulating the temperature in the nesting box is vital.

“You’re treading on a thin line when you’re working with an endangered species,” she said. “You could use the chicken method, which is heat lamps, but that doesn’t work for owl eggs – it can kill eggs ... So making sure the temperature stays cool enough that during the summer months the eggs don’t just cook in the Arizona heat is important.”

Bachofer tested the nest box during a heat wave at her home in Desert Hot Springs, Calif.

“I let the fan and the heat lamp run in my garage when it was around 102 degrees, and it managed to maintain an 83-degree temperature.”

Another challenge: COVID-19.

When Bachofer returned to Phoenix after spring break to clear her things out of her apartment and shelter at home, she also grabbed everything she needed to finish the project.

“My dad and I were just like, we have all the shop supplies in my dad’s garage, so just finish and mail it back. Why not? Just to see the look on the faces of the people at the post office. … They were very confused. Why does this girl have a bucket with a thermostat on it?” Bachofer said with a laugh.

Also because of the pandemic, the team was not able to install its nest box in time for this nesting season, though the box will remain at Wild at Heart for use next season. In the meantime, the researchers will continue to observe the birds, collect data and improve their design.

The hope is that these boxes can be installed in the wild and used as part of the trans-relocation process to re-establish pygmy owls in the Valley.

And re-establishing them is important, Pikstein said. They eat insects and rodents, which means reducing disease transmission and improving agricultural yields. Ultimately, conserving the species "has major environmental and economic implications."

Bachofer, who works at Bancroft Construction Services in Desert Hot Springs, still hopes to one day design prosthetics. She also continues to manage data for the owl project as an alumna and has developed a deeper appreciation for conservation and the cactus pygmy owl.

Added Orr, “We’re stewards of the earth. I just felt called to do something beyond just building my resume and being extra good at school. There’s a personal draw there to help the environment.”

GCU senior writer Lana Sweeten-Shults can be reached at [email protected] or at 602-639-7901.

***

Related content:

GCU Today: Professors unleash inner fan boy, fan girl at Fan Fusion

GCU Today: Game and Fish liaison casts his line at GCU

GCU Today: GCU steps up for black-footed ferret count

GCU Today: Student research on display at symposium