By Lana Sweeten-Shults

GCU News Bureau

Roy Hendrix is tooling around the basketball room of the Interactive Sports Experience iMuseum, strolling between rows of collegiate trophies and vintage leather basketballs, circa 1910.

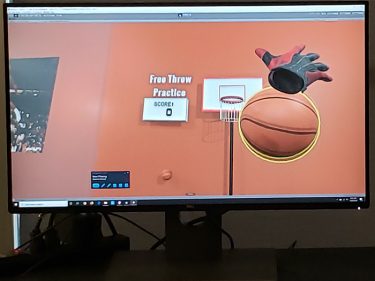

Then he scuttles to another area where he grabs a basketball, plants his feet, positions himself and aims at the net in the free throw practice space. It’s just one of the interactive features at the museum, which isn’t the typical static facility of dusty objects behind glass cases.

All it takes is one glance at Hendrix, whose face looks as if it has been swallowed by technology, to know that this place is something far more cutting edge.

The Grand Canyon University computer science student spent Monday morning donning a futuristic-looking headset and demonstrating his team’s virtual reality project -- a virtual sports museum -- as part of Dr. Isac Artzi’s Human-Computer Interaction class.

The museum doesn’t actually exist in the real world. It lives digitally in the virtual world, visible only through the HTC Vive virtual reality headset. A visitor who wears the headset is immersed in this virtual sports space that no one else can see, unless they, too, wear the headset or glance at a nearby computer screen.

It’s a world Hendrix and teammates Tristan Janisse, Michael Stauffer and Deep Contractor spent the semester creating and then presenting to the campus during a mini-showcase of virtual and mixed reality projects.

“Fifteen weeks ago, they hadn’t even seen these devices,” Artzi said of the VR headsets. Amazingly, just four months later, the students have created a slew of virtual worlds, such as a museum, cadaver lab, the Grand Canyon and White House (visited via virtual tours), an e-reader and even a VR game lounge in which they play a virtual game of tic-tac-toe. “It just shows the power of project-based learning," Artzi added.

It was in 2018 that the College of Science, Engineering and Technology's Human-Computer Interaction Class, or CST 320, tested the virtual reality waters with a VR Bible Project, in which students brought to life various Bible scenes.

This time, Artzi told his students to pick the device, the technology and the topic.

“You create an environment that motivates students to learn, and you give them the resources, and this is the result,” Artzi said.

Just two years ago, GCU’s technology students, mostly computer science majors, had access to one Microsoft HoloLens VR headset. Now the college touts 14 such headsets, adding a few Oculus Quest and HTC Vives in addition to the Microsoft HoloLens. These devices are yet one more tool the University’s students are using to make them more marketable in the technology industry.

Hendrix said he and the other computer science students on his team are sports fans, so they wanted to create a sports museum for their project.

“I had NO experience with virtual reality before, so I was stepping into a new field and just going with the flow,” he said.

The project allowed him to learn Unity, a platform used to create games and other interactive experiences, as well as the C-Sharp programming language and SteamVR, which allows the headset to work with Unity.

“It was overwhelming,” junior computer science major Jared Wermager said of learning everything his team needed to learn as it built its VR project, a skeletal cadaver lab. “This (class) was the first time I put on a VR headset.”

“It was very … ‘Oh, my goodness!’” added Wermager’s teammate, Kelly Walby, also a junior computer science major.

Walby said her team, which also includes William Burchett, decided to create a virtual cadaver lab because she has a lot of friends who are pre-med students and overheard them talking about how they had a hard time transitioning from reading a textbook about human anatomy to stepping into a cadaver lab.

“I thought it would be a really cool bridge to connect those two, so if they wanted to, they could put this headset on and they could have that cadaver environment,” Walby said.

Originally, the team wanted to create three virtual cadavers -- a skeletal, organ and muscular cadaver -- but with just 15 weeks to work on their project, they had to pare their ambitious plans and focus on just one, the skeletal cadaver.

A cadaver lab “visitor" wearing a VR device will see a start-up menu that explains the controls. They then proceed to a waiting room, where classical music is playing – one of “the little fun things that we have,” Walby said. Then users proceed to a hospital bed where they see a cadaver. If they check on a box that says “sternum,” for example, the sternum on the virtual skeleton will light up.

“It goes pretty in depth for the beginning/intro pre-med student,” Walby said.

She sees the VR skeletal cadaver lab as a training tool for high school-level anatomy and physiology students.

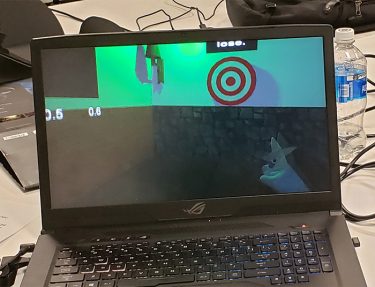

Kyle Jordon, a senior computer science major with an emphasis in gaming simulation, created a dart simulator called Bullseye with his team. Bullseye doubles as both a game and a learning tool. Users play darts in a simulated pub, where graphs of the darts’ trajectory allow the pub-goer to see physics applied in a practical scenario.

“Come and learn about projectile motion in a way that won’t put you to sleep!” is how Jordon and teammates Ben Hebbel, Ryan Jones and Tristen Soto tout their VR project.

“I wanted the focus on having some kind of educational aspect,” Jordon said of Bullseye, which focuses on kinematic equations that relate to displacement, velocity, time and acceleration.

Not that it’s all about physics.

A pub-goer also can pick out some old-school vinyl records to play, such as Dean Martin’s “Ain’t That a Kick in the Head.” Once a user puts on the VR headset, he or she can walk up to a wall of records, chose one, make their way to a record player and place the record onto the player to change the song.

“It’s very ‘Home Alone,’” Jones said of the music feature created by team member Ryan Jones.

Jordon said working on the virtual reality project has been invaluable experience.

“Expanding my horizons – working with different hardware – has been the most important thing. I can program on different platforms, and that’s HUGE,” he said, adding how he loves that he can code for something other than just personal computer games. “This is a good initial step, because in my final project, throughout my whole GCU degree, I’m also going to be working on this software (Unity), as well.”

Artzi sees some of the students’ projects as being relevant beyond the 15 weeks of the CST 320 class.

“This I would like to pitch for the Jerry Colangelo Museum,” he said of the Interactive Sports Experience iMuseum. “… Imagine people walking into the museum and then they have an interaction like this.”

Artzi dreams big: What could students do if they had more than 15 weeks to work on a project? What could they accomplish if someone invested funding in some of these projects, or if students were paid to really build out these ideas?

“I’m very thankful for all the resources we’ve received so far,” Artzi said. “It would be impossible, otherwise, without RDP (the college’s Research and Design Program), Dr. Jon Valla (CSET Assistant Dean) and Dean Wooden (Dr. Mark Wooden), and my associate dean, Dr. Heather Monthie. Without their support, it wouldn’t happen. We need to continue to sustain this.”

You can reach GCU senior writer Lana Sweeten-Shults at [email protected] or at 602-639-7901.

****

Related content:

GCU Today: Virtual reality project bytes into the Bible