By Lana Sweeten-Shults

GCU News Bureau

For Jason Veiock it isn’t so much location, location, location as it is location, remote location, cyber location and security, security, security.

Veiock, a senior manager in Global Employee Safety and Security for GoDaddy, spoke about cybersecurity at a recent Code.org community meetup at the Grand Canyon University-based Arizona Cyber Warfare Range-Metro Phoenix. Veiock was joined by two other speakers at the event, the range’s David Hernandez and Rachel Harpley.

What was surprising is that while Veiock’s job might entail cybersecurity duties, he doesn’t necessarily consider himself a cybersecurity professional.

He said if an investor relations employee, for example, stores the company’s non-public information on his device and then accidentally leaves that device in an airplane seat pocket, “Is that a physical (security) problem or is it an IT problem? Both. It’s a problem. That’s all it is.”

Or maybe an employee gets a call from an angry customer who says, “Do you want me to come to your office in Scottsdale or do you want me to come to your house at 123 Main Street?"

"Is that a cybersecurity problem? That’s not an IT problem, right? At the end of the day, that’s a security problem that has a cyber vector,” Veiock said.

What American companies need in the cybersecurity industry are problem-solvers, he emphasized. Those are the kinds of personalities he advised the many educators in the audience to look out for when it comes to helping build America’s cyber workforce -- a prime focus in recent months for GCU, which has added cyber-focused degrees and has partnered with such organizations as the Arizona Cyber Threat Response Alliance and the Arizona Cyber Warfare Range.

Veiock himself did not get his start in the cyber industry.

“I’m not a cyber guy. I’m not an IT guy. I’m a cop,” he said.

He worked in diplomatic security for about a decade for the Department of State in such countries as Afghanistan, Iraq and Lebanon and served on Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice’s protective detail. He also worked in personnel recovery at the U.S. Embassy in Afghanistan, served on the Joint Terrorism Task Force in Las Vegas and served in the Department of Homeland Security.

“The interesting thing that you learn about all those jobs is that it’s about information fusion," he said. "So it doesn’t really matter what the domain is. It’s about getting information, collecting it, analyzing it and getting actionable stuff at the back end. That’s how I grew into cyber.”

Two years ago, Veiock took a job at GoDaddy’s Scottsdale campus.

"GoDaddy had a need for a gates-and-bars, physical security manager," he said. It didn't take long for the company to ask him if he would take over some cyber responsibilities.

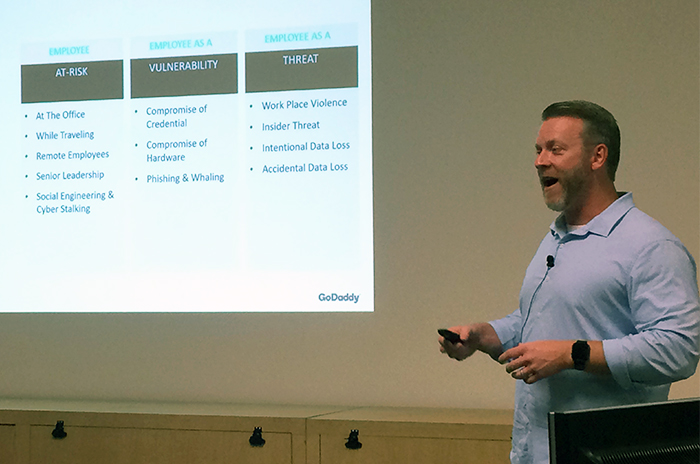

He said he breaks up security in three ways for his company: looking at the employee at risk, which would be remote employees, for example; the employees of vulnerability, which would involve IT issues, such as employees clicking on links or downloading things that might cause a data breach; and then the employee as a threat, which would entail such things as workplace violence or intentional data loss.

“It’s not about physical security. It’s not about cyber security. It’s about the person,” he said.

And the landscape of people at GoDaddy is massive.

“I’ve been there 2 years, 3 months and we’ve bought seven companies,” Veiock said of GoDaddy, which operates in 13 locations in 14 countries and is expanding to new markets rapidly.

That means employees around the world who are given access to digital information quickly, which also can be a challenge for security.

“IT security is how do we surround our data centers, firewall configurations. Physical security, that’s pretty easy. But cyber is really kind of the interaction between the human and the device and the data. I think in five years, it’s just going to be 'security.' I’m not saying you have to be a full-stack developer. I’m not saying you have to code. I’m not saying that you even have to understand all the 1’s and 0’s. But you have to understand how the stuff behind the scenes protects the data, because at the end of the day, that’s all the business cares about.”

Veiock, who spoke just a couple of weeks before Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg testified before Congress, emphasized that the industry is about to change.

“Consent (to access private information) is the best way to get around the Fourth Amendment. But you have to prove that’s legitimate consent,” he said.

The big takeaway he wanted to convey, he said, is to know that devices are part of what we do every day. With privacy concerns and data breaches constantly in the headlines, we need a strong security workforce, and that includes a strong cybersecurity workforce.

“What needs to be taught? What needs to be encouraged? What needs to be learned?” he asked. “I don’t need people that can memorize algorithms. The four-year institutional learning program can’t keep up with technology. When you come here to learn an algorithm, it’ll be antiquated by the time you finish the course. What I need are people that can actually solve problems, that can apply the technology and have a passion for the technology. So for the younger educators in the room, what to encourage – find people that have a passion for that. Encourage that problem-solving, encourage that technology.”

Harpley, Range Recruiter and founder of Recruit Bit, also spoke at the Code.org meetup, touching on the topic of diversity in the industry.

“I think it’s a lot more than just about race,” she said. “Diversity of thought is really important when it comes to security. If everybody on the team thinks the same, you don’t know what the hacker thinks like.”

Harpley said she was part of a discussion where the question was asked, "What would it look like if a woman built the range?"

What came out of that discussion is the Athena Project, or Advancing Arizona Athenas, which is focused on promoting women in cybersecurity.

The group, which has a temporary space for a year, is still looking into the idea of a women-built range, and members have expressed leadership retreats -- not just for them but for youth, too. The Athenas also have started a study group and are looking into creating a get-into-cybersecurity start-up packet that would include a list of industry mentors and the like.

Harpley also talked about the cybersecurity landscape:

“When I was growing up, it was about medical, medical, medical. That’s cyber now, and it’s going to be non-technical roles, auditing, policy, compliance, also the very technical roles. The growth is substantial and one of the reasons is, it is across all industries. If somebody wants to be in medical, they also can be in cyber.

“Cybersecurity is growing, simply, three times the rate of IT jobs. There’s a 2 million (workforce) shortage by 2022, so the jobs are there and they are going to keep being there. Companies are looking at the fact that 84 percent of their applicants are not qualified for the job. That’s stark.”

Hernandez, the community and education outreach coordinator for the range, spoke about what goes on at the cyber warfare range, located in Building 66 near 27th Avenue and Camelback Road.

“A lot of people portray us as these dark hackers. We’re not these types of people, especially the type that movies portray," he said. "We’re not in dark rooms. We are people that get together, share our knowledge with each other. We get along with each other. We’re 20-year-olds, 30-year-olds. But we’re also 90-year-olds, 12-year-olds.”

Hernandez said the range is a no-charge, open facility for anyone in the community who wants to learn about cybersecurity. It’s where people can practice network forensics, which is monitoring and analyzing computer network traffic; hack into websites; or learn how to crack passwords. The goal is to know what the bad guys do so you can counter them.

“We sometimes collaborate with law enforcement in real-world operations. There was a case where there was a kidnapping of a young lady,” Hernandez said. “She was missing for several months. Within four to six hours into the operation, our guys were able to find a location for her, send that data to law enforcement, and we were able to do a full recovery.”

Hernandez's role includes going to high schools and to security events to talk about cybersecurity. He said he has trained about 2,500 students since January

What is disheartening to him at some of those events and workshops is when he sees someone with cybersecurity knowledge not want to help those who want to learn.

“It bugs me when I see that," he said. "We need more hackers in our community, in our educational environment. We need people who are willing to share their knowledge with each other.”

You can reach GCU senior writer Lana Sweeten-Shults at 602-639-7901 or by email at [email protected]. Follow her on Twitter @LanaSweetenShul.