By Laurie Merrill

GCU News Bureau

Take busloads of would-be forensic scientists, put them in front of a “murder scene” and ask them to solve it, and you have one of the most popular activities at Grand Canyon University’s event-packed 2016 Forensic Science Day.

The teams of high school students from across Arizona who attempted to crack the case were among hundreds who participated Tuesday in the annual event showcasing GCU’s Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics (STEM) degrees. (Click here to see photographer Darryl Webb's slideshow from the event.)

“I assume you are here because you love science,” Dr. Jon Valla, College of Science, Engineering and Technology assistant dean, said as he addressed the visitors in GCU’s Arena.

Forensic science isn’t just about solving crime: Forensic science majors must excel in biology, chemistry and other rigorous science classes, just as future biochemists and molecular scientists do, Valla said.

Throughout the busy morning, students heard speakers from the Scottsdale and Phoenix police departments, the Maricopa County Medical Examiner’s Office and GCU professors. They went on tours of DNA and cadaver labs and observed a police dog demonstration.

But the more dramatic events took place under tents outside, where participants tested their abilities in crime evidence reconstruction, fingerprint and handwriting analysis, DNA extraction and more.

Crime Scene Challenge

One of the biggest crowds surrounded the mock crime scene set up by GCU’s forensic science majors.

Two of the sleuths were Sydney Janssen and Ameerah Battle from Betty H. Fairfax High School in Phoenix, who took copious notes as they discussed the evidence.

In the middle of the crime scene lay a female mannequin wearing shorts, a plaid shirt and boots.

“Is that a stab wound on her shirt?” Janssen asked, pointing to a round red spot on the victim’s chest. “Was she stabbed to death?”

The “corpse” clenched a “gun” (actually a green water gun) in her right hand. Two spent cartridges littered the floor. A knife lay near her left hand.

Three wine glasses, each smudged with lipstick, were part of the scene, and the victim wore lipstick, though it appeared she had foamed at the mouth.

“I wonder if there were two or three people?” Janssen said.

“Maybe they had a few glasses before she got murdered and overdosed,” Battle said.

Four plates containing what appeared to be narcotics, marijuana, heroin and cocaine were on the table. Several hypodermic needles were present, and white powder had spilled on the ground near the victim’s head.

Bloody footprints stained the floor nearby.

“It is clear they were drug addicts,” Battle said. “The person lying on the ground definitely overdosed and the gun was put in her hand.”

But a moment later, Battle had a new theory: “The victim fought, fell back, tried to get back up,” she said. “The person on the ground was trying to shoot the other person.”

A team from Mountain Ridge High School in Glendale had other ideas.

“We think that the victim was actually the shooter. Whoever killed the victim was shot. We think she was stabbed,” said Hailey Hudson, a Mountain Ridge junior.

The blood spatters were consistent with blood dripping from a wound, not from high-velocity impact, said Sydney Werbach, another junior.

Furthermore, “the footprints don’t match her shoes,” Hudson said.

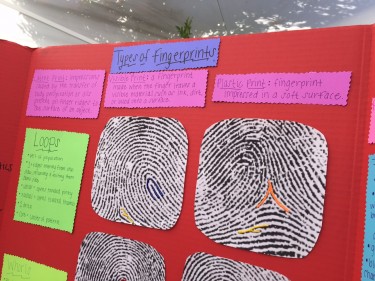

Fingerprint and analysis

While it’s true that every fingerprint is unique, more than 65 percent of our fingertips contain “loops,” said Heidi Bailey, a GCU forensic science major.

Another 35 percent of our fingers have whorls (a pattern of spirals or concentric circles), while only 5 percent have plain or tented arches, Bailey said.

Bailey and other forensic science majors encouraged onlookers to check out their own fingerprints, providing red ink and white paper, and referred to a colorful poster depicting fingerprint characteristics.

Bailey said that latent fingerprints are invisible to the naked eye, but methods such as using powder, putting items in an oven and “superglue fuming” can help investigators identify prints.

'Blood' spatter tent

Easily the most colorful was the “blood” spatter booth, where red, blue and green paint was substituted for the real thing.

Participants garbed in coveralls beat a paint-soaked sponge with a hammer, simulating a suspect fatally bludgeoning a victim, and squirted paint from a tube, mimicking blood spraying from an injured artery.

“This is a blast,” said Kourtney Brown-Hogan, a teacher at Sonoran Science Academy in Tucson.

Analysts gather crucial evidence from blood remnants, including whether a suspect is right- or left-handed, the victim was standing or lying down, or whether they were facing forward or backward, said Julia Howell, a GCU forensic science senior.

Mountain Ridge High School is big winner

The estimated 100 teams that entered the crime scene challenge were asked to identify the scenario, correctly list the important pieces of evidence and how they would process it.

“It was a drug deal gone wrong,” announced Dr. Melissa Beddow, GCU’s forensic science program director.

As it turned out, the first-, second- and third-place winners ─ Ferg’s Faves, the Murder Aprons and Crime Sceners ─ all are from Mountain Ridge High School.

Contact Laurie Merrill at 602-639-6511 or [email protected].